There is no country in the world that has been immune from the impact of COVID-19. By the time that COVID-19 was declared a worldwide pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO), many countries in the Caribbean were already recording its incidence.

No section of society has been immune either. As governments have been forced to introduce lockdowns, many households find themselves without any source of income. This sudden pauperisation has sparked discussion in social media and in the regular press across the region. Governments are being scrutinised over their responses to the poverty induced by the pandemic.

Poverty Measurement

But how is poverty measured in the first place? Official measurement and monitoring of poverty in developing countries came fully into vogue in the 1980s. Concern had developed over the impact of programmes implemented at the behest of the international financing institutions (IFIs) for the provision of support to countries facing fiscal and balance of payments crises.

Hard-hitting critique from the likes of UNICEF led to recoil of the IFIs and to their adoption of human face, decried irreverently, as a ‘face lift’ by the famous Development Economist, Hans Singer. Indeed, the World Bank was to become one of the most authoritative sources for research on poverty.

World Bank conditionalities were no longer going to be imposed without a pro-poor component. Structural adjustment programmes came with measures to protect the poor by Governments seeking IFI support in the face of crisis. The IFIs could no longer be accused of not having a human face.

CDB Studies

The Caribbean Development Bank (CDB), the region’s own institution, was established in the 1970s. From its very foundation under the leadership of the first President, Arthur Lewis, it configured a strategy for poverty reduction, in a Basic Needs approach. The CDB was ahead of the international institutions in focusing on poverty issues.

By the early 1990s, the CDB sought a review on how well its programmes had been performing in addressing the poor in Caribbean states. In the mid-nineties, the Bank started sponsoring studies in member states.

The methodology for measurement applied by the CDB took on board some of the techniques developed by the World Bank with adaptation to conditions in the Caribbean, and later on, it drew inspiration from other sources including Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative.

One of the more significant contributions of the CDB is the attempt to take account of vulnerability. In the approach of the CDB, there is differentiation of the indigent – that those is lacking food adequate to satisfy basic nutritional requirements, the poor – those who though having adequate food, lack other necessities of life. A poverty line is derived which, when applied to data on income and expenditure of all households, establishes who are the poor that fall below the line.

A third category, the vulnerable, on the other hand, while above the poverty line, can descend suddenly into poverty because of a shock that the economy might experience as a result of natural disaster – hurricane, earthquake, volcanic eruption.

A precipitous fall in foreign exchange earnings as a result of problems in the main export sector might result from a crash in commodity prices, e.g. oil prices. In a tourism-based economy, potential visitors might cancel holidays in response to travel advisories, leading to a massive drop in occupancy levels in the peak season. Natural disaster or man-made disaster, political turmoil, spikes in criminal activity impact production of goods including exports, and of services – tourists cancel visits.

Such phenomena leading to decline in foreign exchange earnings are provisioned for in CDB sponsored poverty studies by raising the poverty line by say 25 percent. This might increase the prospective poor by ten percent or more. Thus, a country with a measured poverty of 25 percent could see poverty rise to over one-third of the population as a result of economic fall-out.

Recent Data on Poverty

The CDB sponsored a compilation of poverty studies in the Caribbean in 2016. The data reflect changes in indigence, poverty, vulnerability, and inequality over a ten-to-twenty-year period, in some cases between the 1990s and early in the second decade of the 2000s.

Generally, indigence or food poverty has been reduced to negligible levels over the period. Poverty while still high and exceeding 20 percent in many cases, has trended downward in most countries but by no means drastically so. Very few countries have had percentage poverty rates in single digits.

The Gini coefficient which measures the distribution of income suggests that Caribbean countries still have very high rates of inequality. Indeed, inequality has proved to be more intractable than poverty. Vulnerability estimates where they have been generated show that another ten percent or more of the population would fall into poverty in the event of an economic shock.

In recent years, there is evidence that Governments have improved the administration of programmes designed to alleviate poverty. Transfer payments have been more finely targeted at the poor or at those in need. Thus, indigence in most cases has been reduced to single digits.

In Jamaica, where there has been greatest attention given to the poverty monitoring through regular surveys, the data show that evidence-based social policymaking and interventions have been effective in arresting or reducing poverty and indigence.

COVID-19: A Mega-Shock

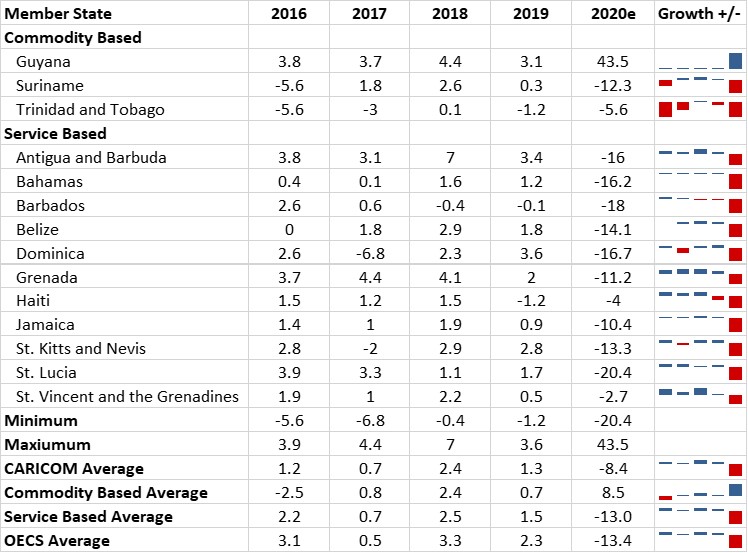

The enormity of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Caribbean economies is revealed in comparison with its impact vis-à-vis natural disasters in recent times. For example, Dominica which was devastated by a Category 5 Hurricane Maria in 2017, suffered a decline in real GDP of 6.8 percent in that year. It is still in the midst of rebuilding of its severely damaged infrastructure.

The shock effect of COVID-19 in 2020 has resulted in an estimated fall in GDP of some 16.7 percent, which is much higher than that occasioned by the natural disaster in 2017. In 2009, poverty in Dominica was estimated to be 28.8 percent and vulnerability at 11.5 percent. Assuming no change in conditions in 2017, as much as 40 percent of the population would have suffered poverty when Maria struck.

With GDP falling by as much as 16.7 percent in 2020, COVID-19 would have reduced a much larger percentage of the population into poverty than did Hurricane Maria when perhaps 40 percent of the population might have found themselves in poverty.

Another example is The Bahamas which suffered in the passing of Hurricane Irma in the same year, 2017. The island of Abaco was laid waste. GDP growth stuttered at 0.1 percent in that year: GDP did not turn negative but grew marginally. However, COVID-19 precipitated a collapse in GDP by an estimated 16.2 percent in 2020.

COVID-19 has been a Mega-Shock. Thus, even without up-to-date data on the poverty situation in Caribbean countries, it can be anticipated that as much as half of the population in some countries of the region might be facing poverty conditions. Indigence – food poverty – would have risen even in countries where it was negligible or did not exist before. In Trinidad and Tobago, there are press reports of stampedes of people in the distribution of free food hampers.

The collective impact of lockdowns, travel restrictions, social distancing protocols, school closures and limitations on social gathering has caused unparalleled social and economic implications across all CARICOM member states. It was the single largest decline in the last 50 years on record.

Guyana was the most significant exception. The country experienced a year-on-year growth of 43 percent on the basis of the first shipments of commercial exports from its offshore oil reserves.

In effect, the pandemic has had economic impacts much larger than has been experienced by way of natural disasters that have afflicted Caribbean economies in recent years. And the loss of life has been greater as well.

Lack of Fiscal Space

Most Governments in the region find themselves with limited fiscal space to increase transfer payments to the poor, let alone to the new poor afflicted by the lock-downs consequent on the COVID-19 pandemic. In attempting to address the fall-out in the form of massive increase in the section of society at risk, Governments have been forced to run huge deficits.

The double-digit decline that has been experienced in most of the countries as a result of the pandemic has to be seen against a backdrop of relatively slow rates of growth in the latter half of the decade. There are few cases of countries consistently achieving rates of growth of 3.0 percent or more regularly over the period 2015 -2019.

Over the last two decades, Caribbean countries have earned the dubious distinction of being among the most indebted across the international community. The 60 percent rule of thumb of Debt to GDP had been exceeded regularly by most countries over the period. Debt to GDP ratios of 100 percent and more are not unknown among Caribbean Small Island Developing States: this means that the accumulated debt exceeds all of the national income for the year in question.

In the more recent past, Governments have made valiant efforts to improve their fiscal operations, by keeping expenditures well within the bounds of the revenue that they can raise. Actually, public debt had been steadily declining on average among member states in the years leading up to the pandemic. The Governments were gradually bringing expenditure in line with revenue.

However, with the pandemic, Governments have been forced to spend heavily on saving lives.

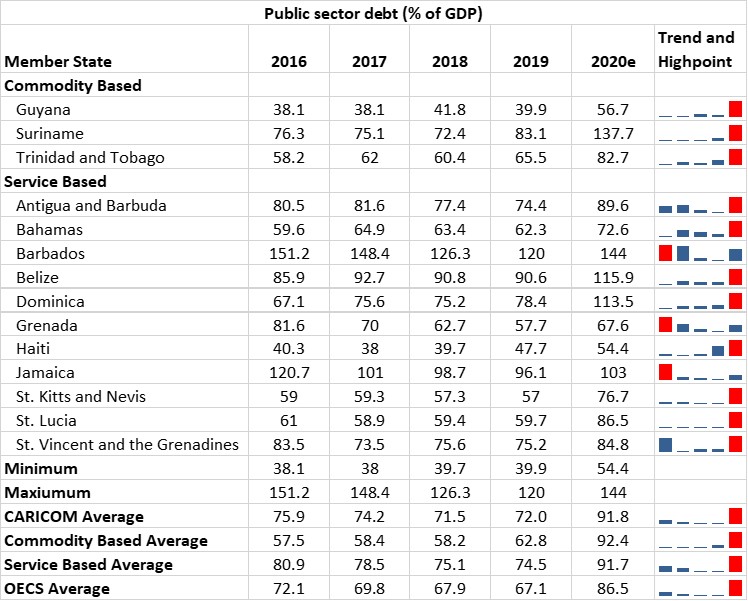

The fiscal measures taken to counteract the social and economic impacts of the pandemic have resulted in considerable increases in public debt regionally. In most countries, the ratio rose in excess of ten percentage points in the one year, 2019-2020, in some cases, even as high as 20 percentage points.

The ratio exceeded 100 percent in Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Jamaica, and Suriname in 2020. The expansion in public debt necessary to treat with revenue shortfalls since the start of the pandemic has pushed public sector debt to GDP in the region up to an average of 91.8 percent which is higher than the internationally accepted limit of 60 percent. Beyond this limit, the international lending agencies normally impose demanding conditionalities in providing loans to countries with higher levels of indebtedness.

IFIs – Saving Lives and/versus Livelihoods

Unlike the stance that might have been adopted in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the IFIs have been more sensitive to the need to save lives in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic which can be compared only with the Spanish flu of a century ago.

As countries around the world faced the effects of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic head on, many international financial institutions (IFIs) intervened not only with the objective of facilitating crisis response, but also macroeconomic recovery through initiatives aimed at saving lives, shielding the poor, buttressing the supporting pillars of the economy, and bolstering institutions and policies aimed at resilience.

Through the World Bank Group’s Operational Response to COVID-19, from the onset of the pandemic through June 2021, as much as $160 billion USD in financing was made available worldwide, tailored to the health, economic and social shocks that countries are facing.

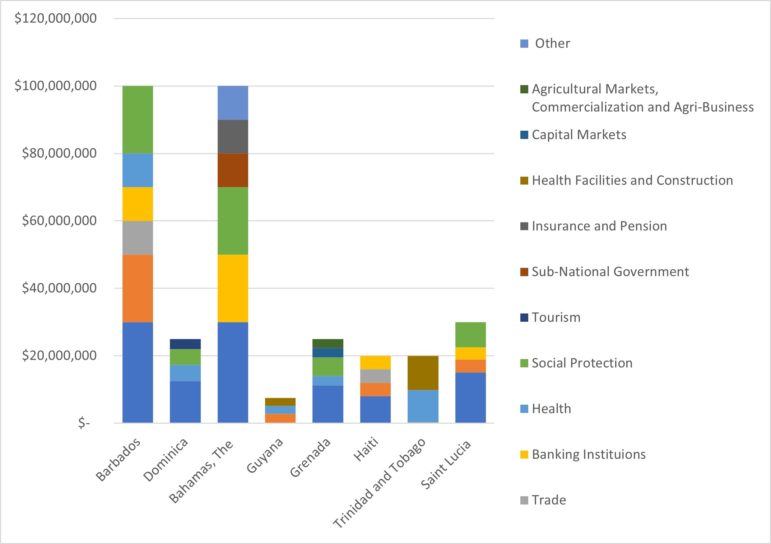

The first recipients of financing through this initiative came through the dedicated COVID-19 Fast-Track Facility, which benefited many countries across the Caribbean Community to the amount of just under $500 million USD.

The vast majority of financing has fallen under development policy lending, followed by investment project financing. While the thematic breakdown of the allocation of the funds disbursed was not available, the sectoral breakdown of World Bank Financing provided to the community can be seen in Figure 1 below.

Source: World Bank Group’s Operational Response to COVID-19 (coronavirus) – Projects List

The data available and the recency of the measures do not allow for the unpacking of the information under the various heads to determine how effectively and efficiently Governments have performed in the saving of lives and the protection of livelihoods. It can be safely affirmed that there have been allocations from the IFIs on both accounts and Governments have increased their expenditures in saving lives even at the risk of exceeding the accepted limits on debt to GDP ratios.

The Existential Livelihood Crisis 2021

There is general recognition that poverty reduction is essentially about creation of sustainable livelihoods in the Caribbean economy. In the short term, the preoccupation might be on groups that have been particularly hard done by the pandemic.

There are the unemployed youth faced with no openings during COVID-19, primary and secondary school students who have lost a year of schooling and could not avail themselves of virtual educational programmes provided by Ministries of Education, women in occupations and sectors with limited or no social security. All these deserve immediate attention.

However, there are macro-economic and meso-level issues to be addressed. At one level there is the matter of industrial policy. Even if there is much more of output that can be organized internally to satisfy domestic/ regional demand with the attendant employment generation (e.g. Domestic agriculture and food requirements of the population), Caribbean countries cannot escape having to export competitive goods and services to secure vital foreign exchange for the goods and services that cannot be derived from domestic production.

The COVID-19 Pandemic has brought into sharp relief the excessive reliance of Caribbean economies on a limited range of exports. The conflicts – China, USA, the European Union and post-Brexit UK – have created fractures in the global trading system.

In addressing the livelihood issue, Governments must be keep focused on the need for economic diversification and for nimbleness of in industrial policy that would allow countries to exit out of activities that cannot survive in an international economy, which even with the protective barriers set in place, will continue to be the marketplace where Caribbean countries must hold their own.

In that regard, the institutionalization of lifelong education and training has hardly attracted the attention and official commitment that are required. This is the sine qua non of having a workforce that can routinely adjust to changes in technology and to the demands of competition in external markets. Constant upgrading will be the platform for sustainable employment in future and therefore in averting the affliction of poverty.

There are other matters that seemingly remote in discussion of poverty, but no less critical. Climate change, the upgrading of the infrastructure to treat with earthquakes, sea rise and the advent of Category 5 hurricanes with greater regularity.

Poverty reduction is about sustainability in the fullest meaning of that word in the context of economic, social, environmental, and technological change. The livelihood agenda has to include all of these issues, which extend much beyond the recovery of the Caribbean economy to the pre-COVID-19 mode.

References

Caribbean Development Bank (2016). The Changing Nature of Poverty and Inequality in the Caribbean: New Issues, New Solutions.

Caribbean Development Bank (2021). Country Economic Review 2020: Compendium.

Gómez García, O. M., Henry; Rosenblatt, David; Zegarra, Maria Alejandra; Frazier, Gralyn; McCaskie, Ariel; Gauto, Victor; Bollers, Elton; Christie, Jason; Khadan, Jeetendra; Abdul-Haqq, Nazera (2021). Caribbean Quarterly Bulletin: Volume 10: Issue 1, May 2021.

International Monetary Fund (2021). “World Economic Outlook Managing Divergent Recoveries April 2021.”

OECS Commission (2021). COVID-19 and Beyond: Impact Assessments and Reponses. An economic and social impact assessment evaluating the effects of the COVID-19 crisis on economies and populations of OECS Member States.

UNECLAC (2021). “Fiscal Panorama of Latin America and the Caribbean Fiscal policy challenges for transformative recovery post-COVID-19.”

World Bank (2020). The Economy in the Time of Covid-19, The World Bank.

World Bank (2020). “Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020: A Reversal of Fortune.”

Statistical Appendix

Table 1: Regional Comparison of Poverty, Vulnerability and Inequality

| Country | Year | Population Poor (%) | Population Vulnerable (%) | Population Indigent (%) | Poverty Gap Index | Gini Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angquilla | 2009 | 5.8 | 17.7 | 0 | 1.1 | 0.39 |

| 2002 | 23 | – | 2 | 6.9 | 0.31 | |

| Antigua & Barbuda | 2007 | 18.3 | 10 | 3.7 | 6.63 | 0.48 |

| Bahamas | 2013 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2001 | 9.3 | – | 5 | 2.8 | 0.57 | |

| Barbados | 2016 | 25.7 | 4.9 | 0.087 | ||

| 2010 | 19 | 10.4 | 9.1 | 6 | 0.47 | |

| 1996/97 | 13.9 | – | – | 2.3 | 0.30 | |

| Belize | 2009 | 41.3 | 13.8 | 15.8 | 11.4 | 0.36 |

| 2002 | 34.1 | – | 10.8 | 11.1 | 0.40 | |

| BVI | 2002 | 22 | – | < 1 | 4.3 | 0.23 |

| 1997 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Cayman Islands | 2006/07 | 2 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.44 | 0.40 |

| 2000 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Dominica | 2009 | 28.8 | 11.5 | 3 | 8.9 | 0.44 |

| 2002/03 | 39 | – | 15 | 10.2 | 0.35 | |

| Grenada | 2008 | 37.7 | 14.6 | 2.4 | 10.13 | 0.37 |

| 1998/99 | 32 | – | 12.9 | 15.3 | 0.45 | |

| Guyana | 2006 | 36.1 | – | 18.6 | 16.2 | 0.35 |

| 1992 | 43.2 | – | 28.7 | 25.1 | 0.44 | |

| Haiti | 2012 | 58.5 | 11.5 | 23.8 | – | 0.61 |

| 2000/01 | 74.9 | – | 31 | 32.31 | 0.61 | |

| Jamaica | 2018 | 12.6 | 3.5 | 0.36 | ||

| 2012 | 20 | – | – | 4.5 | 0.38 | |

| 2001 | 16.9 | – | – | 7.2 | 0.38 | |

| St. Kitts | 2008/09 | 23.7 | – | 1.4 | 6.4 | 0.38 |

| 1999/00 | 30.5 | – | 11 | 2.5 | 0.40 | |

| Nevis | 2008/09 | 15.9 | – | 0 | 2.7 | 0.38 |

| 1999/00 | 32 | – | 17 | 2.8 | 0.37 | |

| Saint Lucia | 2016 | 25 | – | 1.3 | 7.5 | 0.43 |

| 2005 | 28.8 | 40.3 | 2 | 9 | 0.42 | |

| 1995 | 25.1 | 31.5 | 7.1 | 8.6 | 0.50 | |

| Suriname | 2017 | 26.2 | 13.4 | 1.7 | 0.076 | 0.38 |

| 2012 | 47.23 | – | – | – | – | |

| 2005/06 | 8.24 | 6.7 | 3.3 | – | – | |

| St. Vincent & the Grenadines | 2007/08 | 30.2 | 48.3 | 2.9 | 7.5 | 0.40 |

| 1995 | 37.5 | – | 25.7 | 12.6 | 0.56 | |

| Trinidad & Tobago | 2005 | 15.5 | 9 | 1.2 | 4.6 | 0.39 |

| 1989/90 | 18.5 | – | – | – | – | |

| Turks & Caicos | 2012 | 21.6 | 11.4 | 0 | 4 | 0.36 |

Table 2: Real GDP Growth (%) 2016 – 2020

Table 3: Public Sector Debt (% of GDP)