The Scarlet Macaw that thrives in the dense forests of Belize are among the most prized birds in the world. Their impossibly bright plumage of fiery reds, orange, blues and green give a visual hint of their raucous personalities. They thrive on interaction with humans and live for 75 years or more in captivity. All those traits explain why pet owners sometimes pay as much as 15-thousand U.S. dollars to own one.

It is also why poachers invade their nesting grounds every year and threaten their survival.

Poachers once crippled mature Scarlet Macaws by shooting them out of the sky, tracking the wounded birds to where they fell and sweeping them into the illegal wildlife trade. Now they scale towering Quamwood trees to rip chicks from their nests and traffic them across borders.

Half a century ago, populations of Scarlet Macaws in Belize, Guatemala, and Mexico were spiraling toward collapse. Now, according to new data from Friends for Conservation and Development (FCD), their numbers are beginning to steady.

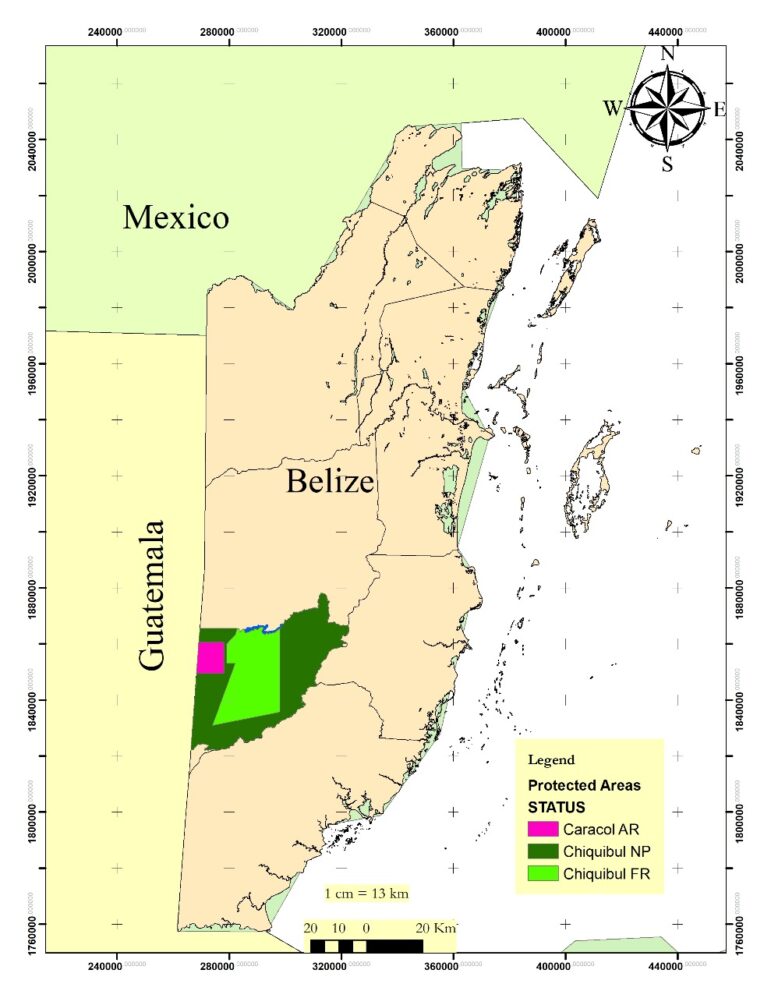

Each breeding season, between February to September, Friends for Conservation and Development (FCD) rangers fan out deep inside the Chiquibul Forest, near the Western Border of Belize with Guatemala. They climb 50- to 70-foot trees to check nests, balancing on ropes and ascenders, to ensure that eggs and chicks survive both natural threats and a darker one: poachers.

A decade ago, as many as 86 percent of macaw nests in the Chiquibul were raided by poachers, according to FCD Executive Director Rafael Manzanero. Today, through relentless patrols and binational coordination, the number has dropped to nearly zero in monitored areas. But Manzanero warns that the threat hasn’t disappeared. He says, “it has simply gone underground.”

“They used to walk three days from Guatemala,” he recalls. “They would climb the same trees we climb, take the chicks, and head back. Up to 25 parrots a year were taken from Belize.”

Each chick taken from the wild fuels an illegal wildlife trade that, according to the United Nations, is worth up to US $23 billion annually, a criminal enterprise rivaling drugs and arms trafficking. In this lucrative black market, a single scarlet macaw can fetch US $5,000–15,000, depending on its size and plumage.

Video Courtesy: News 5 Belize

A Fragile Population

Belize’s macaws belong to a subspecies found only in Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize. Once abundant across the Maya Forest, only 300–350 individuals remain in Belize, according to FCD’s estimate. The Chiquibul is their final stronghold, the only major nesting site left in the country.

The 2024 FCD Scarlet Macaw Conservation Report documents both progress and peril. Rangers monitored 21 active nests, containing 57 eggs. Thirty-seven hatched, and 28 chicks fledged successfully, 19 from natural nests, nine from a field laboratory, where vulnerable chicks are hand-reared before being reintroduced to the wild.

That figure might seem small, but every fledgling matters. Over 12 years of data show that sustained monitoring has slowly pulled the species back from the brink. In 2012, hatching rates hovered around 40 percent; by 2024, they reached nearly 65 percent.

Yet Manzanero cautions that numbers alone don’t ensure survival. “We’ve gone from about 250 macaws in the 1980s to 350 today,” he says. “It took ten years to gain a hundred. We’re confident that with continued permits and support, we can reach 500 but we’re not out of the red zone yet.”

Inside the Climb

At dawn, chief researcher Eric Max and his team prepare their gear beside the Raspaculo River, the macaws’ main nesting corridor. He demonstrates how the rangers use fishing line and slingshot to shoot a line over a sturdy branch, then replace it with climbing rope. “The trees can reach 70 feet,” he explains. “It demands strength, skill, and trust.”

Each climb is non-invasive. Rangers peek inside cavities carved into quamwood trunks, softwood giants that macaws favor for nesting. “We don’t touch them,” says Max. “We observe, record, photograph. We look at the chicks’ feathers, the condition of the cavity, and signs of predators.”

But even nature conspires against them. FCD’s biodiversity researcher Wilmer Guerra notes, the macaws’ own nesting habits endanger them. They return to the same cavity year after year, scraping the wood thinner until the tree becomes structurally weak. “Last year four nests collapsed,” he says. “When that happens, the chicks fall and die. So, we sometimes have to extract them to the lab for safety.”

The FCD’s laboratory, a modest field station deep in the forest, now plays a crucial role. In 2024, 14 chicks were extracted for hand-rearing…most from trees at risk of collapse. Some were later fostered or swapped into safer nests, using protocols refined over years of trial and error. Each chick’s growth is logged, its health monitored, its tiny body implanted with a microchip before release.

The Invisible Market

The threat that once came on foot through the forest now moves more quietly. With increased ranger presence on the Belizean side, traffickers have shifted tactics. Chicks are still taken, but often from unmonitored zones or smuggled through porous border points into Guatemala, where the market thrives.

There, according to José María Castillo, project manager of Asociación Balam, small groups of “collectors” and intermediaries run the trade. “They accumulate between two and fifteen macaws for sale,” he says. “A chick with few feathers sells for $325-400 USD (2,500–3,000 Quetzales), a larger one for $650-900 USD (5,000–7,000 Quetzales), and in the market it can reach $2000 USD (15,000 Quetzales).”

It’s important to know that fledging Scarlet Macaws require almost two years of hand-feeding by their owners to thrive in captivity. The price of a Scarlet Macaw that is fully feathered and developed and ready for sale to an owner can increase many times over. Ultimately, the health and brightness of its plumage is the most important gauge of the price the bird will command in the market.

Most buyers, he explains, want them as status pets, symbols of wealth, not wildlife. “Not everyone can pay that. These birds become trophies.” However, according to Manzanero, there have been rare instances where the birds are eaten. He said, “in some cases some people would actually eat it for the protein. It would be rare, but it would happen. I would assume that if people are way inside the jungle and they don’t have any other protein and that’s the only means that they have then they would go for that.”

Castillo’s organization, based in southern Petén, works with Guatemalan agencies and FCD under a binational action plan launched in 2012 and renewed in 2022. Together they’ve mapped critical trafficking routes, set up a technical working group, and engaged border communities. “We have confiscated only a few birds, four macaws in recent years, but we know many more are taken,” he says. “The traffickers change tactics all the time. It’s hard to keep up.”

He adds that most poachers are not hardened criminals, but rural families driven by poverty. “Many do it because they have no other income. So, we work with communities to offer alternatives, small projects that create livelihoods, so they don’t depend on trafficking.”

“The macaws are like gold bars in a tree…if you leave them unprotected, someone will take them.”

Kurt Duches, Wildlife Conservation Society (Guatemala)

Across the border, in Guatemala’s Maya Biosphere Reserve, Kurt Duches of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) manages a similar fight. “We protect nests in Laguna del Tigre National Park,” he says. “Each pair lays three eggs but only raises two. We take the third chick, raise it in a lab, and soft release it to strengthen the population.”

Like FCD, WCS has seen poaching decline, until recently. “This year we’ve seen an increase again,” Duches admits. “Poachers know when guards aren’t around. The macaws are like gold bars in a tree…if you leave them unprotected, someone will take them.”

He traces the trade chain: local collectors, intermediaries, and foreign buyers. “We’ve had cases of people from Asia coming into communities offering US $50–100 per egg,” he says. “Eggs are easy to smuggle, incubated in suitcases, flown to Miami, then Dubai, Hong Kong, Singapore. It’s that big.”

Despite strict laws, Guatemala imposes five to ten years in prison and a 10,000-quetzal ($1305 USD) fine, few traffickers ever see jail. “They pay a fine and walk free,” Duches explains. “The poor man climbing the tree gets caught, not the one exporting the animal.”

He points out that countries like Peru and Colombia already classify wildlife trafficking as organized crime. “That’s what it is here too,” he insists. “But our system still treats it like a petty offense.”

Belize law presumes anyone caught with wildlife or wildlife parts without a license has committed an offence, punishable by up to a BZ$1,000 ($500 USD) fine or six months in jail. Recent crackdowns show even steeper penalties: a man was fined BZ$5,000 ($2500 USD) for jaguar teeth, and a seized jaguar pelt carried warnings of BZ$10,000 ($5,000 USD) fines.

Minister of Sustainable Development, Orlando Habet, says, “So as soon as someone is caught, they’re informed of the violation. They are fined. There are sometimes when the person prefers to do an arrangement out of court. Many times, they are taken to court and then the court decides on the fines based on the legislation.” Habet believes Belize has strong legislation against illegal wildlife trade.

Belize’s Enforcement Gap

On the Belizean side, anti-poaching enforcement relies heavily on the partnership between FCD and the Belize Defence Force (BDF). Minister of National Defence Oscar Mira concedes that the military faces manpower and logistical challenges. “On the Guatemalan side there are many roads; on ours, none,” he says. “Our patrols are out there every day, but it takes constant effort to minimize incursions.”

The Prime Minister, John Briceño, acknowledges the importance of FCD’s work. “I’ve known FCD for years. I admire what they do,” he says. He agrees that the organization should receive multi-year research permits instead of the current seven-month renewals, which hinder long-term planning.

Without that stability, the gains could unravel quickly. As Duches warns, “If FCD lost its license tomorrow, the first year all the chicks would be poached. The news would spread, and in a few years, the population would vanish.”

The scarlet macaw’s range knows no political boundaries. Adults fly between Belize, Guatemala, and Mexico to forage. WCS has tracked macaws hatched in Belize showing up in Guatemala’s Petén; others born in Laguna del Tigre have been seen in Mexico’s Montes Azules Reserve. “We share one population,” says Duches. “We must protect it as one.”

This trinational cooperation, renewed this year among the three countries, includes data exchange, nest-protection protocols, and cross-training. In Guatemala, rangers have developed egg-incubation expertise; in Belize, FCD leads on field monitoring and on-site rearing. “We learn from each other,” says Manzanero. “To save these birds, it has to be regional.”

Habet agrees. He says the work that FCD does is crucial to the Scarlet Macaw’s survival.

More than $45,000 USD was specifically earmarked for Scarlet Macaw Conservation in 2024 from the Nature Trust of the Americas and private firm Fortis Belize. But FCD notes that volunteers, local leaders and veterinarians contribute vital manpower and expertise needed to succeed.

Threats on the Horizon

“From 250 to 350 took us ten years. If we stop now, we could lose it all.”

Rafael Manzanero, Friends for Conservation and Development

Poaching is no longer the only danger. Climate variability, forest fires, and illegal cattle ranching are eroding habitat faster than macaws can adapt. “The scarlet macaw nest in trees that are 60 to 80 years old,” Duches explains. “If the forest burns, where will they nest, feed their chicks?”

The FCD report echoes this concern: structural nest failures increased in 2024, likely due to an extended dry season. Rising temperatures are also altering breeding cycles, some seasons starting early, others delayed. Guerra believes more research is needed to understand how climate affects nesting success.

Meanwhile, rangers who strive to protect both wildlife and natural resources continue to face personal risks. Castillo notes that his colleagues in Petén have been threatened by armed traffickers while intercepting illegal timber trucks. FCD’s own anti-poaching dog, Sarah, was killed by a jaguar earlier this year while on duty in Chiquibul.

The scarlet macaw’s fate now hinges on continued cooperation and political will in both Belize and Guatemala. FCD’s 2024 report urges a five-year management agreement, greater access for ranger patrols, and enhanced training in veterinary care and post-release monitoring. Without sustained support, the fragile recovery of Scarlet Macaw populations could collapse.

“From 250 to 350 took us ten years,” says Manzanero. “If we stop now, we could lose it all.”

High above the Chiquibul canopy, a flash of red cuts through the morning mist, a reminder that some treasures are worth more alive than any price the black market can offer.

Friends for Conservation and Development (FCD) co-manages the Chiquibul National Park and the Chiquibul Cave System. FCD focuses on landscape-level conservation by protecting biodiversity, critical water sources, and strengthening local partnerships.

Asociación Balam is a Guatemalan NGO that promotes conservation and sustainable rural development through research, capacity building, and strategic public–private partnerships. With over 20 years of experience, it works across key regions of Guatemala to strengthen environmental governance, livelihoods, and climate resilience.

WCS Guatemala works to protect the country’s ecosystems by supporting government efforts, empowering communities, advancing science, and promoting sustainable livelihoods to conserve species and landscapes.