Venezuelans today are torn at every level. Between two current Presidents, two current Parliaments, two socialist rulers over 20 years, first with the popular Hugo Chavez and today the unpopular Nicolas Maduro.

Two decades of noose-tightening by the U.S. to topple the socialist reign sitting on the largest oil reserves in the world have succeeded in isolating Venezuela from even its staunchest supporters and eroded its main source of revenue, oil. The country that was once flush with cash is now broke and importing gasoline. Venezuelans have been dependent on imports for decades, now they can’t afford even the bare minimum daily needs such as food, medicine and clothing when available. Hyperinflation has rendered the currency worthless.

Today, two very different generations live side by side.

Older Venezuelans benefited from the country’s oil bonanza in the seventies through the nineties. They also witnessed their country’s transition from liberalism to hardcore socialism. There’s a younger generation that only knows life under socialist rule and an unstoppable downturn of the economy.

Nearly 5 million Venezuelans have fled to neighboring Latin American countries but remain, struggling to get by.

Caracas-based Ana Matute, journalist for El Nacional who describes her work as “covering the common man,” reached out to the Venezuelans living through the worst economic ordeal of their lifetimes.

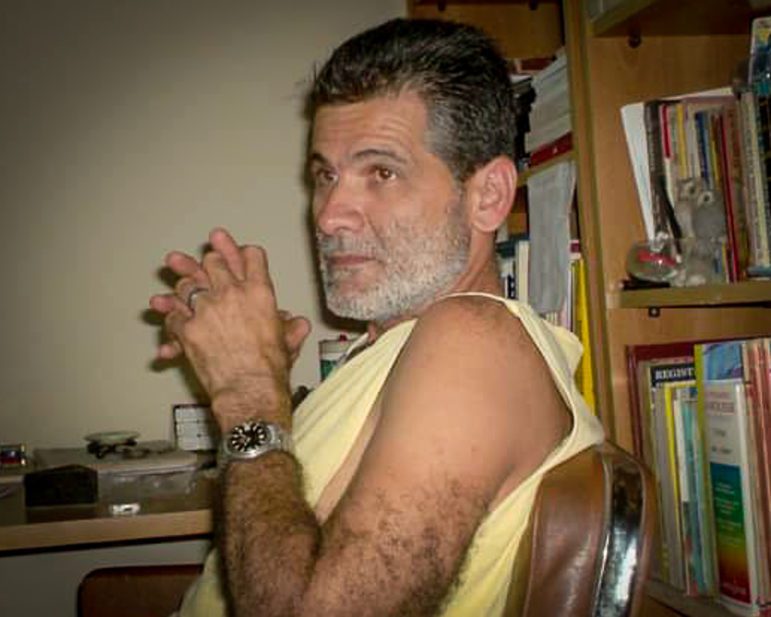

Freddy Garcia

Freddy Garcia, a 59-year old former electrician recalls the good days when he worked as an independent contractor doing electrical maintenance for condominiums and commercial buildings in Cabudare, in the state of Lara. “It was a very good job and I could easily support my family,” says Garcia.

But in 1999, things started to change. “When Hugo Chavez came to power, everything started to get complicated,” recalls Garcia. He described a chain reaction that ultimately led him to abandoning his job. “Materials I worked with were harder to find. Companies slowed down production of parts because of the increased costs and exchange rates. When I did find the parts I needed they cost six times as much. It’s a whole chain. I had to increase service fees and my clients couldn’t pay me.” Owners of residential and commercial properties stopped using his services. “I finally had to quit,” says Garcia.

And life in Cabudare started to change. Garcia says the once vibrant and commercially rich town came to a standstill. “There’s no money, there’s a lot of unemployment. We no longer produce our own vegetables or have livestock. Without money nothing moves.”

Garcia says he has lost hope. “I don’t see the desire to change things. There’s so much pettiness, personal interests,” he says of the politicians fighting for power, blaming them for the doomed economy. “There’s no political strategy to change things and you can see it with the naked eye.”

Belkis Bolivar

Belkis Bolivar has also endured the long economic descent but unlike many, she doesn’t blame US sanctions. “Don’t come telling me that the sanctions have affected Venezuelan people, because the crisis we are living now existed long before sanctions were imposed.” Like Garcia, Bolivar witnessed the transition that began when Hugo Chavez came to power in 1999.

She has been teaching languages in state colleges for the past twenty years. Today she makes US$ 2.70 a month. In her interview with Ana Matute, Bolivar described what it’s like to survive on her meager salary. “With what I earn I can only afford to buy one sack of precooked flour and a carton of 15 eggs every two weeks. That’s not enough to feed my family.”

The Teachers’ Federation of Venezuela estimates that it takes US$ 227 to feed a family of five for a month. To make ends meet, teachers like Bolivar hold two jobs, teaching during the day and giving private tutorials or adult education classes in the evening. “With all the hours I work, I end up making US$ 5 a month.” Two jobs aren’t enough, says Bolivar, who says teachers have had to reinvent themselves. “If not teaching classes, many teachers resort to the informal market, selling second-hand clothes or pastries on the side,” explains Bolivar, “there’s just no way out.”

Bolivar says that it’s not only salaries that are abysmal, but the deteriorating conditions in state schools and colleges since the Education Ministry stopped funding maintenance. “Electricity is sporadic and we don’t have water,” says Bolivar, “I don’t even want to think about the start of the school year,” adding, “some buildings have only one toilet for 700 students.”

Like Garcia, Bolivar points the finger at the opposition politicians, including Juan Guaido’s camp. “The problem is cheapness, ego, the hunger for power. If we don’t unite, we’ll never be able to generate the change that is necessary now.”

Francis Guillen

Francis Guillen is a 31-year old nurse, proud of continuing a family tradition in the profession. She’s worked for eight years at the Miguel Perez Carreno hospital in Caracas, one of the largest in the nation. In her interview with Ana Matute, Guillen described how life has grown even harder since Nicolas Maduro took over in 2013 following Hugo Chavez’ death. Although she earned only US $3 a month, Guillen said she supplemented her income by babysitting. “It’s amazing to think that eight years ago, that really helped. Today, even if I work 24 hours, I can hardly get by.”

Guillen recalls her years as a ten-year old, before Hugo Chavez came to power. “My parents’ salaries as nurses could provide for all our needs, our studies and even the occasional vacation.” Today, Guillen says she and her husband cannot afford the slightest luxury. “As hard as we work, we cannot afford even buying an icecream for our little boy who doesn’t understand why there isn’t money.”.

Asked about her trust in the opposition offering a way out, Guillen says she doesn’t have time nor the desire to listen to the politicians. “My priority is to survive and give my son what he needs. I don’t believe in speeches. I’m tired.”

Luis Alejandro Salazar

At the other end of the political spectrum are the very young hopeful Venezuelans, like Dr. Luis Alejandro Salazar, a 25-year old doctor who decided to remain in the country, while most of his graduate fellows went abroad. He decided to pursue his studies to become a surgeon. “If there’s noone to finance their studies, there’s no reason to apply, because you simply won’t eat.”

Salazar is one of the fortunate ones that got help from his family. “I want to learn the old, basic techniques. While they are no longer used in most parts of the world, Venezuelan doctors know how to save lives with the little we have.”

Saving lives despite the deteriorated conditions of hospitals, Salazar remains convinced that he stayed for the right reasons.

“It’s one of the reasons why I decided to stay here. I don’t know why, but I sincerely belive that this martyrdom we’re living will end.. I feel the government is not going to last long. I know that Guaido has good intentions and is capable of unifying us, and I repeat, that’s why I am staying here.”

“No One Knows the Reality on the Ground”

“All Venezuelans can do is to try to get by, daily, with whatever they can, and just keep to themselves, ” says JV who asked we not publish his name for fear of reprisals.

JV is among many young Venezuelans entrepreneurs that learned business administration, went to neighboring countries, like Colombia, in hopes of finding a good job. But it was just as hard, says JV, who packed up and came back home to start a small donut stand, despite the odds.

“We started with nothing. We found a dilapidated storefront and rebuilt it from scratch, doing all the carpentry, installing everything, little by little by bartering what we had, clothes, CDs, you name it, to get money.”

Last March, JV went to Miami to buy goods for his store, but instead got stuck there for months because of the coronavirus pandemic. He tried various ways to return to Venezuela but could not because of US Sanctions affecting airlines. While waiting to get back to Caracas, JV spoke to CIJN about being caught in the middle. “We’ve been manipulated by the Maduro side and the opposition, and the countries, like the US, that have imposed sanctions. No one knows the reality on the ground.”