Look at Venezuela through the eyes of the people who live there and have endured years of corruption and economic hardship. Hyperinflation has reduced the value of the official currency, the Bolivar, to essentially zero. (For 2019 the world bank estimated inflation was 10 million percent.) Most transactions are now carried out in U.S. Dollars.

Though conservative estimates say a family of 5 needs USD $225 a month for food, salaries regulated by the State only provide anywhere from USD $3 to USD $10 a month. Food packages and allowances do not begin to cover even a fraction of that. Doctors are selling Amway products. Students are shunning University degrees that will only earn a graduate USD $3 a month.

How do people survive? Ana Maria Matute, a journalist for El Nacional, has written a moving personal account that you can read here: Journalism is an escape in a devastated Venezuela. You are also invited to read the views from people of different walks of life in Voices of Venezuela. From his hometown of Acarigua, in Portuguese State, Jose Chalhoub shares his Postcard from the Provinces.

What follows here is a summary analysis of how the people of Venezuela are held hostage by a failed political system, a failed economy, and geopolitical rivalries they are powerless to control.

Destination: Disaster

In assessing the situation in Venezuela, CIJN finds a nation choking on corruption and political deadlock that only worsens. Despite unprecedented political and economic sanctions from the U.S. with support from more than 50 other nations, Nicolas Maduro remains in place.

Meantime, Venezuelans are trapped in the crossfire of their deadlocked domestic politics and competing global and regional interests. These competing geopolitical forces take scant note of the burden ordinary people must bear.

“The situation in Venezuela is as bad as it could be,” says Tamara Taraciuk of Human Rights Watch. “People are struggling to get access to food and medicine, amidst COVID.”

That struggle has consumed most Venezuelans who are now just trying to put dinner on the table, gas in the car and keep the lights on amid power blackouts. Most have lost faith in any promised political salvation.

“My priority is to survive and give my son what he needs. I do not believe in speeches. I’m tired.”

Frances Guillen – Age 31, Nurse

“All Venezuelans can do is to try to get by, daily, with whatever they can, and just keep to themselves.”

Businessman – Name withheld

Analysts are convinced the leadership is in no danger of collapse. The Nicolas Maduro regime has parlayed the country’s resources of oil, gold, and whatever official cover it can provide to criminal groups into cash. It has used that cash to keep its own military and regional paramilitaries loyal to Maduro. Loyalists are appointed to key positions they are completely unqualified to administer. The result is disintegrating infrastructure like the state-owned oil company (PdVSA), the electrical grid, water supplies and more.

Maduro remains in place at the price of Venezuela coming apart at the seams. Shortages of everything from clean water to fuel, the national currency to healthcare all loom large as Venezuelans suffer a constant deterioration of living standards. Coronavirus threatens to push Venezuelans even further toward the abyss.

The country may collapse, notes Dr. R. Evan Ellis, a research professor and veteran Latin America watcher, but the Maduro governments is not going to fall “any time soon.”

With a Lot of Help From his Friends, Maduro Gets by

Russia provides Nicolas Maduro with diplomatic cover, moral support and more. Venezuela once owed Moscow USD Billions in loans made to support the regime, its oil industry and military.

When the U.S. sanctioned Rosneft Trading in February of 2020, the firm sold key assets to an unnamed Russian entity linked to the government rather than endanger its global trading deals. The sanctions had already forced Rosneft Trading to halt all oil shipments on behalf of PdVSA and the Maduro regime. Those shipments had been used to pay off Venezuela’s debt.

For Vladimir Putin, the political stakes may be much higher than the economic ones. Moscow wants to demonstrate it can shield its socialist allies in Latin America against the U.S., just as it did with Bashar al Assad in Syria. The overthrow of a pro-Russian government in Ukraine in 2014 has not been forgotten. Putin has made it clear he considers the U.S. support for Ukraine as meddling in politics on his doorstep.

Russian military contractors (Wagner Group) have provided security for Nicolas Maduro and dress in Venezuelan military fatigues. The same Wagner Group contractors have been active in Syria and Ukraine.

China has nurtured its ties to Venezuela since the early days of Hugo Chavez’ “Bolivarian Revolution.” Politics aside, China saw Venezuela’s huge oil reserves could play a part in its own economic future and sought to invest in the energy sector.

But the direct oil shipments have stopped, leaving China owed at least $19 Billion USD. Beijing suspended payments on that debt at least through the end of 2020.

Both China and Russia have reason to fear that if Nicolas Maduro is pushed out, they could be forced to take painful “haircuts” on any debts they are owed.

Russia and China have both staunchly defended Nicolas Maduro in the face of growing U.S. sanctions that target him, his relatives and key military and political supporters. Both countries say the U.S. is trying to bring about “regime change” in Venezuela by crippling Maduro’s access to the international financial system controlled by Washington.

Russian diplomats persistently stress the U.S. has no right to choose who should lead another nation. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs echoed those sentiments saying it is up to the people of Venezuela to decide for themselves, adding that as a sovereign state, it is no one’s “backyard.”

That narrative ignores how Maduro has murdered, tortured, or locked up his political rivals, banned them from competing in elections and maintained tight control of state-owned media.

In September, the United Nations Human Rights Council published the findings of a year-long independent mission to investigate abuses. The Mission probed hundreds of cases and remotely interviewed more than 3,000 witnesses before releasing its 411-page report.

U.N. Human Rights Council Report on Venezuela

The Mission found that high-level State authorities held and exercised power and oversight over the security forces and intelligence agencies identified in the report as responsible for these violations. President Maduro and the Ministers of the Interior and of Defense were aware of the crimes.

They gave orders, coordinated activities and supplied resources in furtherance of the plans and policies under which the crimes were committed.

“The Mission found reasonable grounds to believe that Venezuelan authorities and security forces have since 2014 planned and executed serious human rights violations, some of which – including arbitrary killings and the systematic use of torture – amount to crimes against humanity,” said Marta Valiñas, chairperson of the Mission.

“Far from being isolated acts, these crimes were coordinated and committed pursuant to State policies, with the knowledge or direct support of commanding officers and senior government officials.”

The government of Nicolas Maduro criticized the report charging the United Nations was politicizing Human Rights. It branded the report part of a “Ghost Mission” because the investigation was conducted from abroad and U.N. staff did not enter Venezuela. The U.N. explained that despite repeated requests, Maduro’s government barred the U-N investigative team from entering the country.

Cuba

Venezuela’s main socialist ally in the Western Hemisphere is Cuba. Havana provides doctors and other health workers to the Maduro government. It also provides thousands of state security agents accused of helping suppress Venezuela’s opposition. Cuba receives 66,000 barrels of Venezuelan crude oil per day. There is no clear reckoning whether Havana pays for it.

Even Cuba’s doctors are cause for controversy. The opposition claims Maduro’s government pays around $2,000 a month for each Cuban medical professional in the country while Venezuelan nurses earn less than $5 per month.

In Venezuela there is not a power struggle for the leadership. There is a dictatorship that is sequestering the revenues of the state, from the petroleum industry and all the sectors that it depends on, as well as the illegal sale of its gold, from its narcotrafficking, from corruption. There is an entire country fighting to gain back its dignity and we are all suffering.

Juan Guaido – “Interim President of Venezuela”

Though clearly pushed into the spotlight by the U.S., only a small number of Venezuelans regard Juan Guaido as an effective political force capable of ending Maduro’s grip on the country and restoring representative democracy. Venezuelans, in fact, put little trust in any politician.

Guaido’s support and that of Nicolas Maduro have both declined. In fact, they are tied for almost last place in the most recent polls at less than 10%.

But Guaido is still backed by the U.S. and more than 50 other nations. In an interview with CIJN, Guaido said the obvious: the opposition must unite to bring about democratic change.

Guaido put forward a plan that parallels the proposed U-S solution. That solution would see a caretaker government taking over control of the country (including the military) and both Maduro and Guaido stepping aside until free and fair elections could take place. Guaido’s plan envisaged the opposition refusing to take part in the Dec. 6 elections while Maduro still controls Venezuela’s media and state resources.

International political forces, once again, made that impossible.

Turkey Steps In

Turkish diplomats negotiated a deal between Maduro and another opposition figure, former Presidential candidate Enrique Capriles, who said he would join in helping Maduro. No one inside Venezuela failed to see through Turkey’s motives. Maduro had already declared that to avoid U.S. sanctions, he would be refining Venezuela’s gold in, of all places, Turkey.

The result predictably divided Venezuela’s political opposition. Those joining Capriles’ defectors have taken to calling Guaido “President of the Internet,” mocking his international support and de-facto ban from speaking or appearing on Venezuela’s airwaves.

As polls indicated a backlash by voters, Capriles walked back his position and said even he might not cast a vote. But the damage is done; the opposition appears in disarray. Ordinary Venezuelans are tired of all politicians, including those in the opposition.

“The problem is cheapness, ego, the hunger for power. If we don’t unite, we’ll never be able to generate the change that is necessary now.”

Belkis Bolivar – Teacher

To further convince the opposition he wanted to turn the page, Maduro ordered the “pardon” of what the government said were more than 100 prisoners ranging from members of the National Assembly to activists and labor organizers. Maduro told the U.N. General Assembly in September it was evidence he was a willing negotiator.

One of some two dozen members of the National Assembly who was released told CIJN it was nothing more than a political ploy. CIJN has withheld his identity.

“In Venezuela there have been thousands of political prisoners. They lock up citizens to later release them and thereby generate the (favorable) impression.”

The lawmaker warned “(Maduro) should never be taken seriously, he is a criminal and will remain the criminal he has always been.”

Many of those released have described harsh conditions where they were held without proper sanitation or healthcare. Some were handcuffed to beds and slept on the floor. Others were held for months in windowless cells.

Within hours of announcing the “pardons,” the Maduro government reminded those released that they are all subject to being arrested again if they commit a “crime.”

Iran Defies U.S. to Ship Fuel to Venezuela

Iran sailed into the fray by sending tankers filled with fuel and refined products that could bolster Venezuela’s sagging oil exports. U.S. sanctions enabled the seizure of more than a million barrels aboard 4 tankers in August. The cargo was turned over by shipping companies unwilling to run afoul of U.S. sanctions.

Iran undoubtedly finds common cause with Venezuela because it, too, is confronted with “maximum sanctions” by Washington.

Elliot Abrams, the Special U.S. Representative for Venezuela and Iran, told CIJN, the shipments are still too small to make any real difference in the situation. Iran’s motive, he said, is to trade its fuel for Maduro’s gold.

“We told ship owners, insurers, ship captains, this is all sanctioned and the sanctions are going to be enforced…they need to stay away from Iran, and they need to stay away from Venezuela.”

Iran persists, using its own flagged vessels. In September 2020, amid street protests, more Iranian gasoline was delivered to Venezuela.

Elliot Abrams was a controversial pick for the post. His past defense of pro-U.S., right wing governments in Central and Latin America accused of serious Human Rights abuses sparked protests and debate at his confirmation hearing.

Abrams told CIJN “the sanctions go when Maduro goes.” Abrams has the task of pushing Juan Guaido forward as the leading candidate to replace Maduro, a tall order if you check public opinion polls. A September survey by Meganalysis found only 6.1% of Venezuelans who support the opposition favor Guaido’s leadership. Though clearly Washington’s pick, the young politician has been unable to unite the opposition or move even a step closer to replacing Nicolas Maduro.

Meantime, the U.S.-led sanctions exacerbate the shortages that plague Venezuela today. But there is ample evidence the long decline of Venezuela’s economy and oil industry began more than a decade before sanctions were imposed.

At fuel stations in Caracas, people queue up for hours for gasoline. In rural areas, the wait in line could be days or longer. While some of the supply is earmarked for ordinary citizens, bitter complaints and even confrontations are reported as those with connections to the regime jump the line and fill up before others even have a chance.

In his “Postcard from the Provinces,” Jose Chalhoub writes that politics is no longer the main topic of conversation among ordinary Venezuelans. The availability of fuel, basic services, the economy, and COVID-19 have pushed politics off the page. People are not taking to the streets to demand political change. But clearly, they are willing to take risks for what matters most to them.

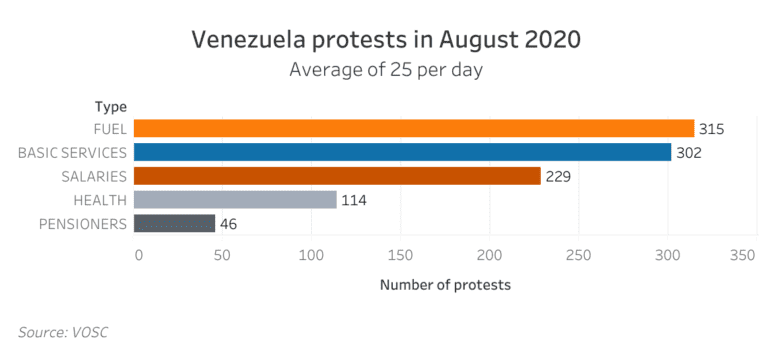

The Venezuelan Observatory of Social Conflict (OVCS) registered 748 protests in August 2020, equivalent to an average of 25 daily. 40% were about fuel. An almost equal number were about basic services like electricity, domestic gas, and water.

“The country is moving towards a greater political polarization in the coming months and probably a weakening of the democratic opposition… The most affected will continue to be Venezuelans who, in the midst of their struggles for a better quality of life, will be defenseless.”

The Venezuelan Observatory of Social Conflict

U.S. Sanctions and Venezuela’s Humanitarian Crisis

The U.S. Congress passed the Venezuela Human Rights and Civil Society Act of 2014, requiring the President to impose sanctions on anyone responsible for significant acts of violence or serious human rights abuses. It specifically targets anyone who orders the arrest or prosecution of individuals for exercising their legitimate right of freedom of expression or assembly. The Act has been extended through 2023. It marked the beginning of a wave of economic and political sanctions.

President Barack Obama issued an Executive Order in 2015 targeting persons found to be undermining democratic processes or institutions as well as other elements listed in the Act. It imposed financial sanctions as well as revoking U.S. visas.

Pres. Donald Trump’s administration transformed that wave into a veritable tsunami of sanctions, indictments, and economic penalties.

By August of 2020, the Congressional Research Service reported:

“… the Treasury Department has imposed sanctions on more than 150 Venezuelan or Venezuelan connected individuals, and the State Department has revoked the visas of more than 1,000 individuals and their families. The Trump Administration also has imposed sanctions on Venezuela’s state oil company (Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A., or PdVSA), government, and central bank.”

While most of the sanctions directly affect only the individuals named, there is no doubt that economic penalties against the government and the state-owned oil company have contributed to Venezuela’s economic decline. Historically, oil was 90% or more of Venezuela’s export earnings. Today, ship owners and insurers refuse to risk taking on cargoes of Venezuelan crude in fear they will be hit by sanctions like others.

Still, the U.S. point man on Venezuela, Elliot Abrams, insists the sanctions do not affect the humanitarian situation.

“First of all, there are the individual sanctions on members of the regime which certainly don’t hurt anybody else,” he told CIJN. “On the economic side, we always exclude humanitarian goods, so they can buy all the food and the medicines that they want. We don’t think the sanctions against the Maduro Central Bank or the sanctions against PDVSA, the oil company, are hurting the average Venezuelan.”

Abrams and U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo say more aid than ever is flowing to Venezuela.

“Well, there is more money going in than ever before, that is true,” says Human Rights Watch (HRW) Deputy Director of the Americas, Tamara Taraciuk. “But that is largely due to the enormous pressure that has come from democracies around the globe pushing the Maduro regime to accept this aid. The problem is when it gets into the country, humanitarian actors do not have full authorization to operate openly and nationwide. The government has still not accepted that the World Food Program be deployed in Venezuela, which is the only institution, with partners on the ground, that can effectively reach the (entire) country.”

HRW and many others say it is a battle over control of the food aid. The Maduro government wants to use it to repay loyalists and shore up its sagging credibility with average Venezuelans. Yielding control could give its opponents the most powerful tool imaginable to undermine the regime.

Taraciuk is adamant. “We’re talking about a regime that has proven to be corrupt and has minimized the humanitarian emergency that it has helped create,” she told CIJN. “So it’s very difficult to know, when there are absolutely no guarantees, that if it had in fact gotten the money…(it) would have been used to benefit the humanitarian situation that the Venezuelan people are suffering from.”

The tightening grip of U.S. economic sanctions faced by shipping companies, insurers, and anyone else trying to do business with Venezuela has prompted many to halt trade with Caracas. The sanctions block Venezuela from transactions within the global U.S. financial system.

Moreover, the sanctions are vague in some areas and subject to rapid changes. This goes beyond oil shipments and can interfere with humanitarian aid efforts.

HRW’s Taraciuk says explicit exemptions for humanitarian aid are not working as intended.

“What we found in our research, is that in practice, that is very difficult because there’s over compliance,” she said. “Financial institutions err on the side of caution in this situation and this can have an impact on the humanitarian situation on the ground.”

In the Caracas slums, the poor take care of each other. Women run soup kitchens to try to keep those with no resources from going hungry. The Catholic Church and other charities have similar operations on an even larger scale. The government distributes food packages, but critics say they are prioritized for Maduro’s supporters and government workers. Multiple schemes to exploit humanitarian aid for profit have been exposed, including a USD $2.4 Billion money laundering operation that siphoned millions from Venezuela’s emergency food aid program.

Anti-Narcotics Interdictions by the U.S. Military and Allies

In March 2020, the U.S. unsealed indictments charging Pres. Nicolas Maduro and others with narco-terrorism, corruption, and drug trafficking. It marked another chapter in Washington’s standoff with the Venezuelan regime.

The head of the Constituent Assembly, the former Chief of Military Intelligence, the vice-President for the economy and a former general each had $10 million rewards posted. The bounty on President Maduro was $15 million.

Attorney Gen. William Barr laid out the U.S. case that Maduro permitted a splinter group of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) to enjoy a safe haven inside Venezuela for its drug smuggling operations as well as an armed insurgency across the border.

The Trump Administration has already deployed more naval vessels in the Caribbean and Eastern Pacific to intercept drug shipments than at any time in the last 5 years. Ground forces have also been deployed in the region along the border between Colombia and Venezuela where cocaine is produced.

Anti-Narcotics operations in the Caribbean and Eastern Pacific yielded more than $1 Billion in drugs seizures by July 2020. The U.S. Navy and Coastguard has been aided by the deployment of AWACS, specialized surveillance aircraft and refueling tankers.

The Deputy Commander of the U.S. Southern Command told CIJN, “We have enhanced our counter narcotics operations both in the Caribbean and in the Eastern Pacific and over the last several months that has had some very effective results.” Lt. Gen. Michael T. Plehn said more than 56 metric tons of cocaine had been seized or disrupted.

The deployment of that many military resources is not cheap. It likely outstrips even the billion-dollar haul in drugs. But the Trump Administration shows no signs of pulling back on the military front.

Coronavirus Complicates the Ordeal

The arrival of COVID-19 in Venezuela has been met with fear, face masks and lockdowns. While “essential” businesses providing food can remain open in most cases, others must deal with a schedule of one week open followed by a week when they must shut down.

For months, the government released data showing little exposure to Coronavirus. But few took the government numbers seriously.

The opposition reports infections and deaths are more than double what the Maduro government reports. The statistic that stood out by the end of September 2020 was that more than 200 of those deaths have been among doctors and medical staff.

The head of the Venezuelan Medical Federation (FMV) said “We are the ones who bear the brunt of this death.” Douglas Natera bitterly a crowd who gathered to pay tribute to health workers that 95% of Venezuela’s medical workers do not have the proper protective equipment and are paying with their lives.

The death rate of doctors and other health workers in August 2020 meant 30% of Venezuela’s COVID-19 deaths are among those who are on the front lines trying to treat infected patients, according to the FMV. To put that in perspective, deaths among healthcare workers in the U.S. account for a tiny fraction of 1 percent of the overall death toll and are still considered far too high.

Meantime, criticism is being leveled against Nicolas Maduro’s government for using the pandemic to further control the politics, protest, and criticism.

“COVID is a perfect excuse for the regime to crackdown, using health as an excuse,” HRW’s Tamara Taraciuk told CIJN. The government has raided gatherings and uses the military, armed with assault rifles, to enforce the coronavirus lockdown orders.

A blistering report from HRW, published at the end of August, 2020, details how the government and military are using the pandemic as an excuse to crack down on dissenting voices and intensify their control over the population.

The End Game

From Caracas to Washington, Moscow to Beijing and across Latin America the chief concern is how this will end? Venezuelans themselves are far more concerned with when will it end? Until now, both questions have gone unanswered.

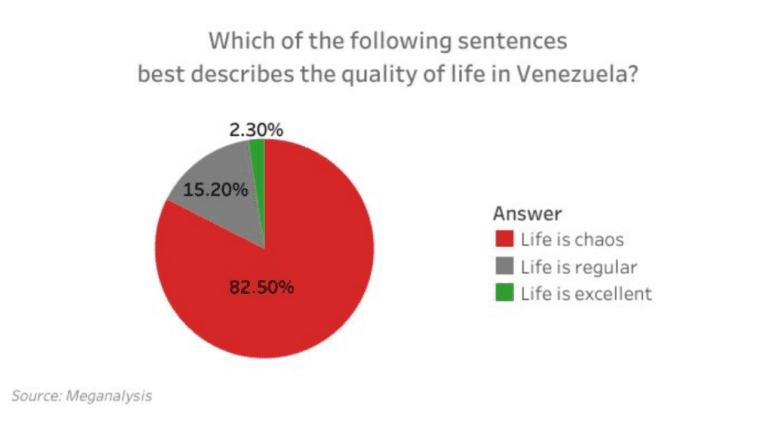

A survey conducted by Venezuelan polling firm Meganalysis in September 2020 revealed the current state of a struggling nation.

Asked to describe their quality of life, an overwhelming 82.5% of Venezuelans chose “Life is Chaos” over “Life is Excellent” (2.3%) or “Life is Normal” (15.2%)

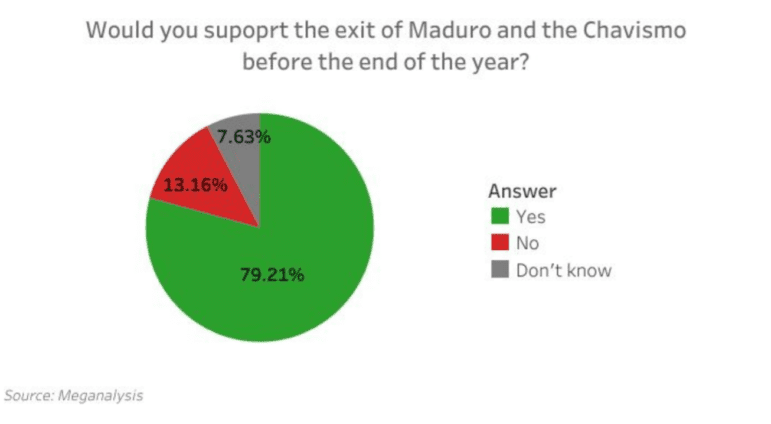

Meganalysis Vice-President and CEO, Ruben Chirino Leanez told CIJN that years of sifting through the attitudes and opinions of Venezuelans shows that today they feel they are being held hostage by their own political class. Most, he said, do not believe there can be an improved economy without an end to the Maduro regime and the public overwhelmingly wants it sooner, rather than later.

An overwhelming 79% of Venezuelans said they supported the end of the Nicolas Maduro regime by the end of 2020. Only 13% remain in support.

Both Juan Guaido and Nicolas Maduro fared poorly in the poll. When nominal supporters of both the opposition and the Chavista movement were asked which politician they trusted, a majority in each camp responded “No one.”

You can view more findings of the Meganalysis poll here.

Maduro’s call for elections on December 6th is a date to watch. Would a dismal turnout send a message that his time is up? Would he hear that message? Maybe a better question is would the people he owes money in Moscow and Beijing want him to hear it?

Michael Shifter, President of the Inter-American Dialogue points to another black box: Venezuela’s military. Guaido has been imploring the military to join with the opposition without visible success. In the wake of the U-N Human Rights report, some military men have more cause to fear prosecution if the Maduro government were to suddenly be removed or step aside.

What Venezuela’s military may not fear is direct U.S. military intervention. While Washington’s point man Elliot Abrams told CIJN “all options are on the table,” he also stressed the U.S. would continue the existing policy of sanctions and economic pressure.

Meganalisis CEO Ruben Chirino Leanez told CIJN the “great majority” of Venezuelans are depressed and discouraged. They are under pressure from the crisis of basic services, the “invisibility” of facts surrounding the coronavirus threat and the reality their incomes cannot support their families.

The unimaginable economic burden Venezuelans have been forced to bear prompted an estimated 5 million or more to leave the country. Some of Venezuela’s best and brightest may never return. That comes at a cost to the entire neighborhood.

“What’s concerning to me…and our partners in the region is the effect that outflow has had on both their ability to lend support to those migrants but to their own people as well. It’s straining resources in the region,” said Lt. Gen. Michael Plehn.

“So, if you wonder whether or not Venezuela matters to regional security – absolutely! Because it’s beginning to chip away at both security and stability in the region.”

“What worries me the most,” says Dr. R. Evan Ellis, “is that the situation is going to deteriorate such that it’s going to fall into a South Sudan, Somalia situation.”

The failed state scenario might provoke a change in leadership, but Dr. Ellis warns that is no guarantee the next leader would be more democratic or respectful of human rights.

He sees how criminal groups involved in gold mining, drug smuggling and other illegal activities are thriving off the current situation.

“When I look at the dynamics, I see that it will continue to deteriorate into violence, and chaos, and bloodshed, and at some point, Maduro will be deposed. But that does not mean you will have democracy there,” Ellis told CIJN.

That could certainly spoil the celebration for supporters of regime change.

Andy Knight, Professor of International Relations at Alberta University said Russia, China, Iran, and others were acting out of self-interest. He told CIJN “I would say the U.S. needs to get out as well…it’s time for them to step aside and allow a more neutral group of states to…try to get these sides together at the bargaining table.”

Not unlike Washington’s own public position, Knight says the Venezuelan people need a fair and honest election monitored by the International Community. Knight also contends that botched attempts to overthrow the Maduro government by force have compromised U.S. credibility. Sweeping economic sanctions, he insists, are hurting Venezuelans more than their leaders.

But Venezuelans themselves are not putting the blame on sanctions. Meganalysis CEO Leanez:

“For the majority of Venezuelans, the main causes of any serious situation in the country are socialism, the Chavista government headed by Maduro and the traditional political “opposition”… that, far from achieving a change of government, have ended up oxygenating the Maduro administration.”

The E.U.’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs, Josep Borrell, conceded in early October that the Norwegian-E.U. effort to mediate between Maduro and the opposition had failed. Borrell warned there is “no cathartic event” on the horizon that will magically solve the crisis.

Failed politics and global rivalries hold some 30 million Venezuelans hostage. No one claims to have a solution. Everyone agrees there is no end in sight. Chaos is the only commodity in abundance.