The Legislative Challenge

Even as Caribbean authorities wrestle with the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, legislators have been scrambling to formulate appropriate responses to an accompanying growth in unlawful pyramid and Ponzi schemes marketed as financial solutions to the impact of restrictive pandemic measures.

The Caribbean labour market report released by the International Labour Organization (ILO) in December says that “as expected with a significantly reduced output production and deteriorating trade flows and fiscal space, the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the labour market in the Caribbean has been massive.”

Despite the use of cash transfers and other financial relief packages to citizens of territories such as Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Montserrat, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, The Bahamas, and Trinidad and Tobago, a state of economic uncertainty has prevailed.

In most instances, unpredictable macro-economic conditions are being met by populations nervous about household financial fortunes.

In an interview with CIJN, Robert FitzPatrick, president of the North Carolina-based non-profit organisation Pyramid Scheme Alert, said such conditions are ripe for exploitation.

“Pyramid schemes do very well in bad times,” he said, adding that COVID-19 “has restricted work tremendously. You’ve got all these people now unemployed: They are not chronically unemployed — they are recently, and through no fault of their own, unemployed.”

They are also being encouraged to stay home to avoid infection. “So along come these pyramid schemes saying: ‘this is a replacement; it’s an income opportunity’. And it’s based on being at home; you can do it online,” he said, adding, “So they have exploded actually during the pandemic.”

In the Caribbean, quick short-term financial schemes offering huge returns have thus gained increasing popularity, especially as many of them masquerade as traditional informal savings clubs. In almost all instances, though, they have left a narrow trail of quick financial gain, but a much larger footprint of misery and distress.

CIJN estimates that the rash of pyramid and Ponzi schemes has already cost would-be investors in the hundreds of millions of dollars in the six jurisdictions examined by the Network – Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, British Virgin Islands (BVI), Guyana, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago (T&T).

Regulatory responses have been largely deficient, despite a pre-pandemic history of spectacular crashes involving sophisticated cross-border operations spanning recent decades. There has in fact been little regional collaboration on finding a suitable regulatory response, and patchy solutions have straddled everything from consumer law to anti-trust legislation.

Guyana’s attorney general, Anil Nandlall, told CIJN the issue needs to be pursued “as a matter of urgency” at the regional level, through CARICOM and the Caribbean Financial Action Task Force (CFATF).

Though financial fraud involving both formal and informal non-banking operations has plagued the region in past decades, many countries, including T&T and Antigua and Barbuda, have never explicitly banned pyramid and Ponzi schemes.

But even in countries with specific regulatory prohibitions against pyramid and Ponzi schemes – such as Guyana, Barbados, Jamaica, and the British Virgin Islands – such operations have flourished during the pandemic, often under the guise of traditional saving systems known variously as “sou-sous”, “box hands”, “partners” and “blessing circles.”

In recent months, regulators across the region have warned about the phenomenon, but have struggled to stop it. In 2012, a National Anti-Money Laundering and Counter Financing of Terrorism Committee (NAMLC) was established in T&T and consumer protection legislation was formulated to address the issue. It remains pending.

There is a Financial Intelligence Branch (FIB) in T&T – the arm of the police services charged with prosecuting financial crimes – but proposed legislation is yet to be laid in Parliament.

Under Section 80: 2 of the draft Consumer Protection Bill, a pyramid scheme is defined as “anything which (a) provides for the supply of a good or service or both for reward; (b) in relation to the participants of a scheme, constitutes primarily an opportunity to sell an investment opportunity rather than an opportunity to supply a good or service; and (c) is unfair, or is likely to be unfair, to many of the participants.”

“This (operation of pyramid schemes) needs to be outlawed. We are playing catch up. Countries like St. Vincent, Grenada, Jamaica, and other Caribbean countries all have legislation like this. This legislation is necessary to put an end to this nonsense,” an FIB source told CIJN.

In Jamaica, back in 2017, following the collapse of the case against the head of Cash Plus, a multi-million-dollar scheme that left thousands in financial distress, the island’s Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP), Paula Llewellyn, had called for more focused legislation.

“Our legislators would demonstrate great wisdom, given the history of failed investment schemes in Jamaica, and our cultural affinity for generating wealth through ‘partner’ plans, to augment our legislative framework to assist prosecutors in meeting public demands on, and expectations of public prosecutions,” she was quoted as saying.

“It is ideal to do this sooner rather than later.”

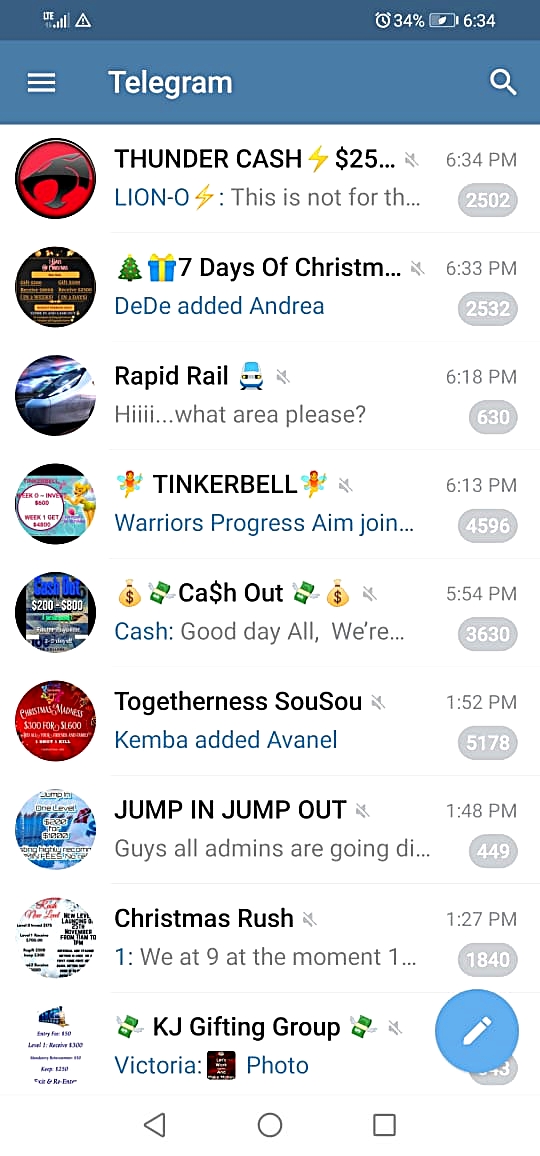

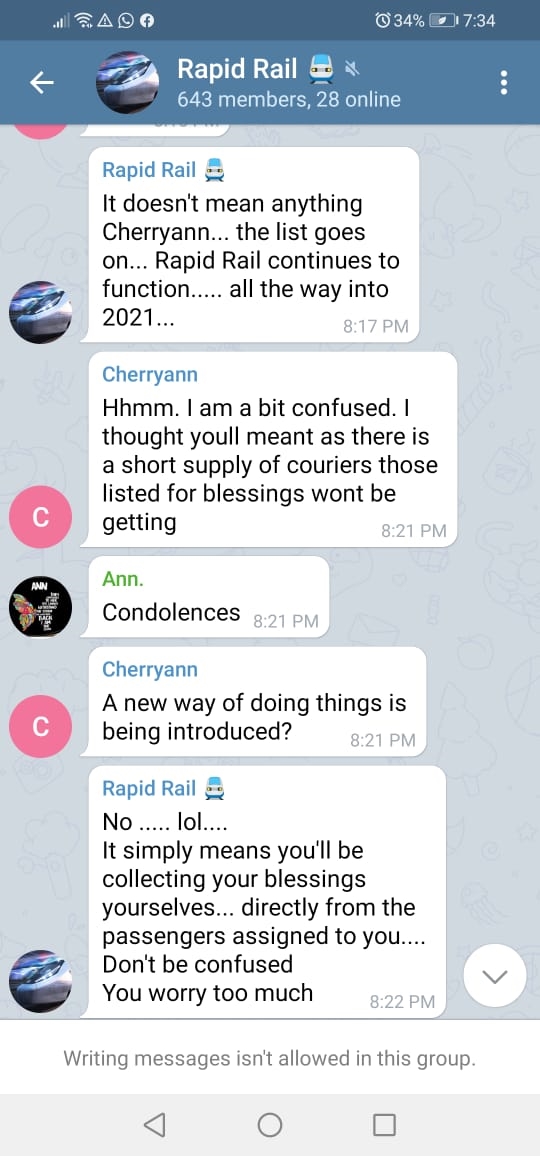

Since then, the widespread use of social media and messaging apps has changed the nature of the game. Some authorities argue that existing regulations in the region – including the pyramid bans themselves – do not apply to the modern schemes, which often operate on messaging platforms like WhatsApp, Telegram, and others.

This has left a situation in which scammers have been allowed to operate essentially in plain view of the authorities.

In Antigua and Barbuda, for instance, regulators complain they are left with a 1916 law to prove their cases. It is a country which, at the turn of the century, served as a base for the second largest Ponzi scheme in history.

In 2012, Antigua-based Allen Stanford, who led the Stanford Financial Group of Companies, was imprisoned in the US for 110 years after being charged by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in 2009 with operating a sophisticated, cross-border Ponzi scheme worth an estimated $8 billion.

Today, popular schemes are offering buy-ins of as little as $10 in the twin-island state. But Derek Benjamin, senior financial analyst at the Office of National Drug and Money Laundering Control Policy (ONDCP), said there is no local legislation criminalising such ventures, though they could potentially lead to civil lawsuits

Even so, he told CIJN, the chance of getting one’s money back is “tricky”. “For the time being, there are no prohibitions that will prevent pyramid schemes from existing,” he said.

“The danger of course is logical. There is going to be a time when investors will not be able recruit additional participants and therein lies the problem. There will be a large base of persons who will be waiting to receive re-imbursements,” Benjamin added.

The regulatory system in the British Virgin Islands (BVI) has been steadily beefed up over the past four decades as the territory’s financial services industry has grown rapidly. There is now a Financial Services Commission (FSC) as regulator and an autonomous Financial Investigation Agency (FIA), both of which work closely with the police when needed.

But representatives of all three agencies said during a forum in August that BVI law enforcers historically have struggled to prosecute pyramid schemes.

“We find it very difficult to investigate these matters,” police Detective Sergeant Elvis Richards said. “Why? There’s no paper trail and sometimes the persons who are really involved in these schemes are not known. … Sometimes people do not want to report because of shame.”

In Guyana, Nandlall stated bluntly: “We don’t have legislation.”

“That is why in these cases, we had to go back to common law offences of fraud, conspiracy to defraud, obtaining money under false pretences, et cetera,” he told CIJN.

Nandlall pointed out that while Part V of the Guyana Consumer Affairs Act, No. 13 of 2011 prohibits pyramid selling, it only covers goods and services and not financial investments.

“We have some reference to a pyramid scheme referred to in one of our consumer legislation but it deals with the supply of goods and services on a pyramid type basis, but that has no relevance to the type of pyramid scheme where you invest and the pyramid builds and the last layer at the top pays for the layers at the bottom and that is how it builds going up,” the attorney general explained.

Nandlall served as AG from 2011 to 2015 and he was appointed to the position again on August 2, 2020.

He noted that “Ponzi schemes in the way that this one has been manifested, and the way that Ponzi scheme is known generally in the world, we don’t have any laws that speak directly to that activity.”

It is a comment he was willing to generalise to apply to the entire Caribbean region.

He pointed out that while the country’s Anti-Money Laundering/ Countering of Financing Terrorism (AML/CFT) legislation may indirectly speak to this type of situation, “that’s not the thrust of the anti-money laundering laws.”

After the pandemic has moved on, he suggested, it will be something to address on a regional level.

Case Files

Guyana

In Guyana, Cuban national Yuri Garcia Dominguez, and his Guyanese wife, Ateeka Ishmael, were arrested in August and accused of operating a Ponzi scheme under the banner of Accelerated Capital Firm Inc. (ACFI), which allegedly had acquired some $27 million from about 17,000 members. The pair pleaded not guilty, and authorities said at the time they had been unable to recover any of that money.

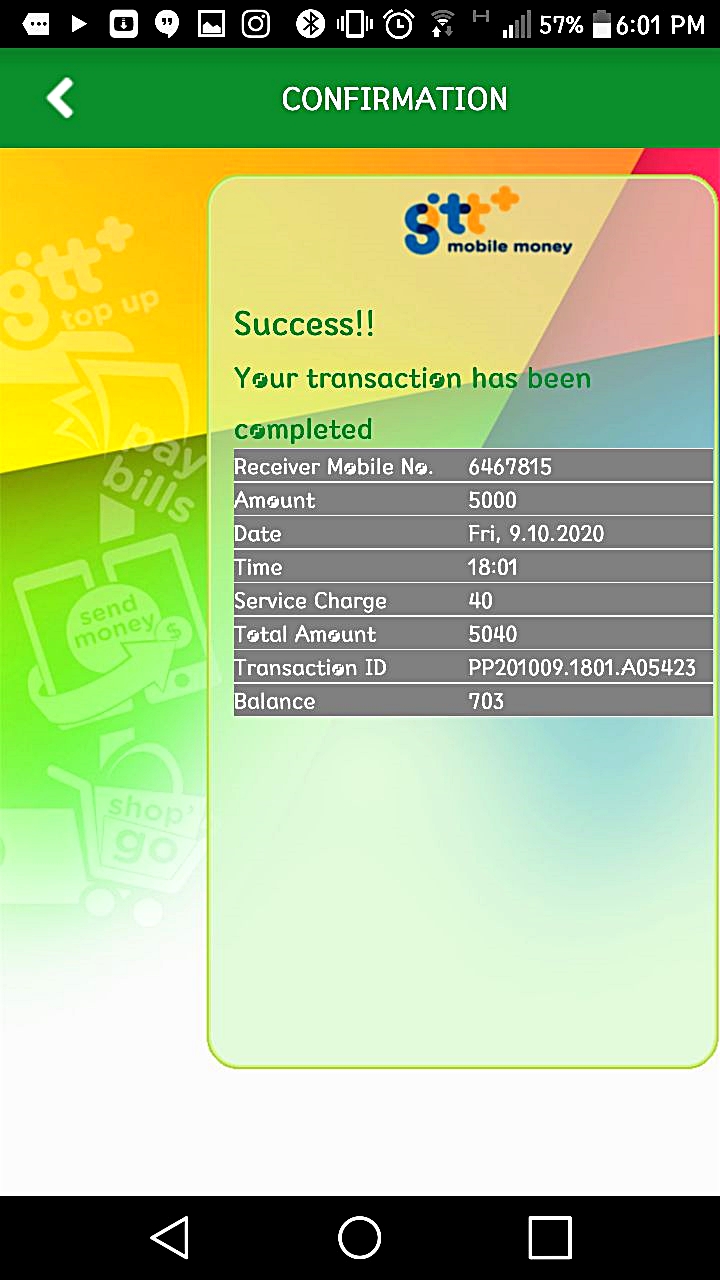

ACFI was big, but not the only players on the block. By reviewing social media groups hosting four schemes that appeared to operate similarly, CIJN was able to calculate that an estimated $5,000 per month had within months passed through these operations, which involved 631 people who had either benefited or have been left empty-handed.

Under common names like ‘1k to freedom’, ‘Group B’, and ‘Freedom Family’, unsuspecting citizens were asked to invest as little as $5 in order to receive a promised return of up to eight times their contribution. In Guyana, $40 is equivalent to a labourer’s weekly income. The three schemes combined were able to attract 539 persons.

In another scheme with 92 persons called ‘Bless and be Blessed,’ participants were asked to invest $25 to earn a return of $200.

The schemes went on from April and lasted for months. During this time, subscribers were able to receive returns. However, as time passed, fewer people were willing to come on board and things started falling apart.

Trinidad and Tobago

When T&T contractor Trevor Smith heard about the Drugs Sou Sou (DSS), it seemed too good an opportunity to pass up. The 42-year-old – who was struggling economically amid the Covid-19 pandemic – had been denied a loan to pay his workers, and the DSS billed itself as an investment opportunity promising returns of up to 600 percent.

So, he visited DDS headquarters – a family home in La Horquetta, a neighbourhood situated in the east of Trinidad – and made two cash payments of $555 each. A payout initially promised in 28 days did not arrive, but after 40 days he claims to have received $7,300.

Buoyed by this success, he then sent five additional payments totalling $7,200, and, when he spoke with CIJN in December, was awaiting promised returns of close to $40,000.

But the money may never come. In October, the DSS apparently collapsed amid arrests and allegations that it is a fraudulent pyramid scheme.

Nevertheless, Smith, who said he also sent money to other schemes with mixed success, believes DSS was targeted because it provided financial liberty to participants, especially those of African descent.

Asked if he regretted his investment, Smith said, “Nah! Is not DSS fault, so nobody have any issue with DSS. Is the police. DSS worked for me. Great is the DSS!”

Back in July, the DSS in T&T, led by army lance corporal Kerron Clarke, was offering returns as high as 600 percent and advertising itself as a way for black people in the country to gain financial liberty.

Unlike other schemes on the twin-island nation, DSS did not require members to bring others on board, but organisers remained tight-lipped about how it was able to offer the promised rewards.

Many participants did not care: The promise of six times their initial investment was enough to attract them.

By August, however, the scheme had attracted the attention of the police, and on Sept. 22 police raided a house in La Horquetta and reportedly seized more than $3.5 million.

Shortly thereafter, they returned the money. All this sparked widespread controversy, including claims that the operation had been unfairly targeted, that there had been a misapplication of the law, and that some of the money seized by the police had gone missing. But more raids followed.

On October 27, 2020, the police seized just over $1 million dollars from Clarke, who has continued to defend his operation as a legitimate investment opportunity.

This seizure, the fourth cash confiscation by police in three months of operations, crippled the scheme. Many people who lost money, while claiming they had participated in a legitimate “sou sou”, blamed the police.

Regarding DSS, the FIB officer said those who lost money did so because they were greedy. He added that there is no “investment vehicle” in DSS so there is nothing to show how returns are made.

“What they do is pay out a few people who serve as town criers to get others to invest,” the officer said. “But there is no investment. When you get six times your input, where do you think that money is coming from? These people just greedy and they are paying for their greed.”

Susan Singh, a mother of three who spoke on the condition that she be identified by a pseudonym, does not think herself greedy.

“I just wanted some money to fix up my place and pay off some loans,” she said when asked why she invested $800 in DSS.

Like Singh, Smith just wanted a way out of financial uncertainty.

“Since DSS shut down it have others that popped up, bigger than DSS and running,” said Singh, who lives in La Horquetta, where DSS headquarters is located. “It have over 23 sou sou running. I invested in some others, I get paid in some and some I didn’t. None like the DSS. DSS was really a great investment.”

Singh, like Smith, believes that her seized cash will not be returned. It is something they have accepted as they both agreed that DSS “was a risk.”

Prime Minister Dr Keith Rowley meanwhile declared DSS a “cancer that will eat the soul of this nation.”

To mitigate the risks of another explosion, the FIB officer hopes that the legislative framework already drafted will be implemented.

In the interim, both the Barbadian and UK governments have been asked to assist in providing the necessary manpower to investigate DSS. Local authorities are yet to calculate how much money was given to the scheme by investors as receipt books have yet to be tallied.

DSS is currently being investigated for money laundering as well as fraud. But Police Commissioner Gary Griffith has on numerous occasions said he could not arrest anyone who invested in or promotes a pyramid scheme but that he can warn people not to fall prey to such schemes.

Since the crash of DSS, suspected investors in the scheme were targeted by banks, which applied more stringent procedures to safeguard their clients’ investments while investigations continued.

Read more about Caribbean Ponzis and Pyramids.

Barbados

Barbados has seen the frauds proliferate in churches under the name “Blessing Circle,” and regulators who warned about the nature of the schemes have been blamed for causing them to crash.

The requirements for participation range from having two new guests simultaneously register to the re-investing of earnings.

CIJN investigations revealed a number of people who said they walked away with payouts of as much as $75,000 after multiple investments and re-investments, but far more are either left awaiting promised returns or have been reeling from the collapse of several “blessing circles”.

One popular entertainer, whose payout had been delayed, told CIJN, “some of the people in the circle had some difficulties meeting the requirements, so I was informed by the head that I have to wait a little bit longer.”

The entertainer said his circle consisted of eight people, but the entire cohort involved over 500. While he declined to disclose how much he had to initially invest or how much he was set to be paid out, he said he was required to reinvest over $1,300 to keep the circle going.

“A lot of these circles have crashed because people are selfish and refuse to reinvest,” he said. “If I walk away with my payout and don’t put back in money, then that is dishonest.”

All of this is despite longstanding, targeted prohibitions. In Barbados, pyramid schemes have been illegal since the passage of the 2003 Consumer Protection Act.

The law states that any person guilty of organising a pyramid scheme could be fined $10,000 or spend two years in prison. Additionally, a company could be fined up to $100,000, and company directors could be fined $25,000 and spend two years in prison.

At the beginning of November, the Sunday Sun newspaper reported a scheme had made its way into a church, resulting in a major fallout after select members of the congregation were asked to contribute $2,700 in return for an eventual payout of $21,000.

However, the scheme crashed, and many were left unable to “count their blessings” or recoup any of their initial investment.

Other circles reportedly have included politicians, entertainers, bank managers and blue-collar professionals, among others.

While some participants have reported earnings, many others have lost sizeable amounts after the schemes crashed.

Dava Leslie-Ward, director of consumer protection at Barbados’ Fair Trading Commission (FTC), said in an October interview with the Weekend Nation that the FTC was considering the best way to investigate the schemes and was willing to work alongside the police.

“It is very difficult to find out exactly who the persons are at the head of these schemes, but that is something we are looking at closer,” she said.

“Given some of the information we are getting, and some of the responses that we get to our efforts to educate the public, it seems we have to look closer at how we would go about launching an investigation, simply because we need to be able to protect the public from themselves.”

Following her announcement, many of the “blessing circles” either crashed or slowed down, with one rebranding itself as a “charity” collecting “donations.”

But despite the FTC’s October warning, Leslie-Ward said in an interview with CIJN in December that no one had come forward. Instead, she added, many scheme participants had accused the FTC of not wanting “poor people to make some money.”

“The people felt we were reaching and did not want us to get involved,” she said.

“People wanted general information, but I did not get that people wanted specific information. They wanted to know what a pyramid scheme is and how it was defined by our legislation, but while they wanted that information, it didn’t seem as though they understood it.”

In response to the schemes, Barbados Minister in the Ministry of Finance Ryan Straughn called for a system to regulate legitimate peer-to-peer lending systems like the traditional sou-sous, meeting turns, or box hands.

“Those things are not fraudulent by any stretch of the imagination,” he said. “But we want to be able to bring legislation that speaks to how they are conducted, so people could have greater confidence if there are disputes, then there is a process by which one can have a resolution. It is something we want to address early in the New Year.”

Straughn added that it would be difficult to prosecute anyone for the frauds.

“Unfortunately, unless there is some kind of contract or documentation, then ultimately it would be John Brown’s word against John Public, to the extent of which the lack of information makes it difficult to prosecute,” he explained.

“That is why we are focused on having these specific things registered so there is a clear dispute mechanism in the event anything potentially caught awry can be dealt with.”

Straughn joined with Leslie-Ward in stressing the importance of education. “People make financial decisions all the time, which are not always in their best interest,” Straughn said.

“That is why the Financial Literacy Bureau is set up to assist and educate people to distinguish what risk-taking is in true investments vis à vis fraud or schemes, which is on a completely separate system from any investment opportunity.”

Antigua and Barbuda

Anaya Summers, a single mother of two who lost her job as a massage therapist due to the Covid-19 pandemic, recently used $100 from her $250 weekly stipend from the Antigua and Barbuda Workers Union to join a group called the Go Getters Club that promised a payout of $800.

The payouts are distributed on a weekly basis and recipients are chosen from a numbering system which is instituted at the beginning which changes as more members are added.

She received the promised $800, she said, and used it to settle an outstanding balance at a local furniture store.

“I was a bit sceptical at first,” Summers said, “but I thought about it and then decided to give it a try because in the worst-case scenario, I would only lose $100. I also felt safe because I knew most of the people in the group including the administrator, who was a former co-worker of mine.”

James Browne, a primary school teacher, said he has benefitted from a similar group that encourages members to “bounce back from a setback.”

A prospective member is asked to bring along two invitees can contribute as little as $10 to receive up to $80, and as much as $250 for a jackpot of $2,000.

“Before this, I was a part of a $10 group, but because of what happened in Trinidad and Tobago with the news that some groups were crashing, some of those members pulled out leaving some who never got a payout,” Browne said.

Nevertheless, Browne said he made money.

Many other residents, however, told a quite different story. Shaniya Andrews invested $50 in a similar group in the hopes of taking home $500, she told the local media.

However, before she could get her payout, the group members realised that the administrator had deleted their WhatsApp group and stopped responding to messages.

She and other residents have made an appeal to law enforcement to help them get back their money.

Such complaints had increased in early July, prompting the police to warn residents to stay clear of schemes which promise huge returns.

BVI

In the BVI, authorities say the frauds operate outside the scope of the extensive legal framework that regulates the United Kingdom territory’s financial services industry.

With about 30,000 residents and a heavy pan-Caribbean population, the BVI has not seen flashy public pyramids like the ones allegedly operating in Trinidad and Guyana, but similar schemes have quietly flourished under the radar during the pandemic.

The schemes have also been masquerading on social media as “sous sous,” “blessing circles,” “box hands” and other names, regulators said during a recent virtual forum organised by the BVI Financial Services Commission to raise awareness about the issue.

But they also said they struggle to prosecute the schemes.

Sometimes, law enforcers are unable to distinguish victim from perpetrator, according to Financial Investigation Agency Deputy Director Dwayne Thomas. The schemes, he said, typically induce victims to market to friends, family, or acquaintances from church and other social groups.

“You went from a victim to a perpetrator when you started marketing,” Thomas said. “The funny thing is, if this scheme implodes and persons can’t get their money back, even though you think you are a victim, you’re also a perpetrator.”

This confusion complicates the matter for police, especially in such a small population, explained Richards, the detective sergeant.

“We have a problem there in who are you going to arrest,” he said. “If that has to happen, we would have to arrest the general public for defrauding each other. It’s very difficult unless you can identify the persons at the top.”

The schemes’ founders, however, often live abroad, outside the reach of local law enforcers, he explained.

Police and the FIA – which was established in 2004 to investigate white-collar crimes such as money-laundering – also have struggled to find victims willing to come forward.

“We don’t see complaints, but we hear stories,” Thomas said. “Yes, we can act on intelligence, but unless we get names, we can’t do anything. It’s a situation where you’re leaving our hands tied.”

However, new legislation might help bring change. A provision explicitly banning pyramid schemes was quietly included in the Consumer Protection Act of 2020, which was passed in July following widespread outrage about price-gouging after Hurricane Irma devastated the BVI in 2017.

The law penalises operating or promoting a pyramid with up to two years in prison and a fine of up to $5,000.

“That is, in my view, a very good start, because there’s a clear and outright prohibition against it,” said BVI Financial Services Commission Director of Enforcement Brodrick Penn.

“Obviously, that is fairly new, and the mechanisms to implement, ensure that the prohibition has teeth, are probably still yet to develop.”

He added that more work will be needed in terms of inter-agency collaboration and other complementary legislative reform.

“I think that’s actually one of the keys to these things: that all the law enforcement bodies, or anybody that has a tangible connection to them, obviously cooperate to put the [pyramid frauds] to a stop,” he said.

Jamaica

In Jamaica, there is evidence that through stringent pandemic measures and accompanying hardships, pyramid schemes have continued to flourish. Officials there had hoped Jamaicans would have learned a lesson through the ill-fated Cash Plus scandal.

The Carlos Hill-led investment scheme, Cash Plus Limited, began in 2002, bolstered by the economic mismanagement in the political and private sector that defined Jamaica in the 1990s.

According to the late former Prime Minister Edward Seaga, the economic turmoil of that decade led many banks to become “heavy investors in projects they launched themselves, departing from their core banking business as lenders.”

“There were tonnes of loans issued to anyone who promised big returns,” university lecturer and social commentator Anthony Thompson told CIJN. He also said this created a vacuum in some sections of society and a high-risk environment for borrowers, lenders and investors.

The first documented inquiry into the legitimacy of Cash Plus came after two published advertisements in a local newspaper in 2004 “inviting individuals to invest $100,000.00 or more and receive a 10 percent return on their investment monthly”.

But by 2007 the Financial Services Commission (FSC), which had been investigating Cash Plus through covert phone calls, document requests and other tactics, released a statement advising that “Cash Plus Limited is not licensed by the FSC to conduct securities business in Jamaica and that Cash Plus Limited’s securities offered to the public have not been registered by the FSC.”

“The Securities Act requires all persons soliciting or conducting securities business or investment advice business in Jamaica to be licensed by the FSC to do so. The Act also requires that securities must be registered by the FSC before they can be issued to the public,” the statement said.

In the end, the FSC never brought any formal charges against Carlos Hill or Cash Plus, even though it is able to initiate proceedings in Criminal Court through Section 6[1] of the Financial Services Commission Act. Instead, it only issued a cease-and-desist order against Cash Plus and Hill. The Court of Appeal later ordered that nine of 26 bank accounts should remain open and allowed Cash Plus to continue its operations.

According to the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (ODPP), the FSC further adjusted its cease-and-desist order in April 2008 to allow Cash Plus to hire a new manager for the purpose of assisting in investor pay-outs.

A classified report was also sent by Charge d’Affaires a. i. James T. Heg in Jamaica to the US Department of the Treasury and the Secretary of State in November 2007.

In this document, titled “Jamaica: “Cash Plus” – A Ticking Financial Time Bomb”, Heg reports that “irrational exuberance abounds among Jamaica’s less experienced investors, many of whom deposit their fortunes with Cash Plus Limited in exchange for promised annual returns of 120 percent.”

The Organised Crime Division of the Jamaica Constabulary Force also launched an investigation into Cash Plus in 2007 following complaints by investors. Hill was eventually arrested in 2008 and charged in 2009 with 15 counts of “fraudulently attempting to induce persons to invest”, under Section 28 (1) (c) of the Larceny Act.

However, Hill walked free in 2017 after the case collapsed for want of witnesses willing to testify, prosecutors said.

The Way Forward

Throughout the region, authorities have warned people against participating in the schemes. But as in T&T, many of them have also contended that they are unable to prosecute the operators.

FitzPatrick, the Pyramid Scheme Alert president, agreed that stronger laws are needed in many countries, but he is generally sceptical of regulators’ claims about the difficulties of prosecuting the frauds. This narrative, he said, is distressingly common, even in the US.

“They go, ‘Oh, they don’t seem to be breaking any laws.’ That’s so disingenuous, really,” he said. “I mean, how could a deceptive income promise that cannot be fulfilled — and in which you have misled the person right from the start that it could be fulfilled — how could that ever be legal?” he asked.

FitzPatrick described a “dividing line” between commerce and fraud.

“It’s based on two things really: deliberate deception and consequent harm. And fraud is fairly easily identified that way. And I know people can engage in fraud unwittingly, but when it’s done in an orchestrated manner repetitively, and when it’s done in a very calculated manner, with leaders and rules, you know this is a racket.”

But, as in Trinidad, prosecuting pyramid frauds can be politically difficult, in part because they often involve thousands of participants who believe strongly in them, FitzPatrick said.

“It’s kind of this magical belief and it is often called a cult, because it has all the attributes of cultism,” he explained. “And one reason is because it is founded on an occultic concept: the concept of endless expansion, which is mathematically impossible, physically impossible.”

Authorities who intervene may get blamed for scuttling the profits that participants believe they are owed.

“It’s a fraud that plays on a blind spot in people’s consciousness and it can only operate on a mass scale,” he said. “In Albania the government was brought down — it has tremendous potential for disruption.”

The collapse of pyramid schemes in that country led to war in 1997 after citizens took to the streets to protest losses which they believed had benefited the government.

All told, two thirds of Albania’s population had invested in the schemes, according to a report by the International Monetary Fund. The resignation of the prime minister did not quell the resulting unrest, and more than 2,000 people were killed before stability returned.

Though the explosive popularity of the “sou-sou” label is relatively new in Caribbean schemes, the region has battled major pyramid and Ponzi frauds under different names for decades. But leaders have not always acted on the lessons learned.

Jamaica’s Securities Act was however amended in 2013 to explicitly prohibit Ponzi and pyramid schemes.

But, even amid the legal amendments and the publicly documented failure of Cash Plus, the Loom (Blessing Plan) emerged in 2018 via social media promising 300% return on investment within one week. This scheme also crashed after the FSC released statements warning individuals and encouraging them to file official complaints with the FSC and report the matter to the police.

One social media personality at the time, Nikki Chromazz, who was heavily promoting the Blessing Plan, said she started receiving complaints and death threats after people expressed concerns due to the reported dangers. No charges have yet been laid.

“It’s a fraud that plays on a blind spot in people’s consciousness and it can only operate on a mass scale…”

FitzPatrick, the Pyramid Scheme Alert president

In the midst of the Cash Plus and other prosecutions and failures including Olint, World Wise, and May Daisy in Jamaica, the International Monetary Fund published a 2009 report on pyramid schemes in the region, noting that the island’s problems were part of a larger trend.

“In several Caribbean states, unregulated investment schemes grew quickly, particularly during 2006-08, by claiming unusually high monthly returns and through a system of referrals by existing members,” the report states.

“Such schemes are pervasive and persistent phenomena and emerge on a regular basis even in developed countries with strong regulatory frameworks, as shown by the recent experience in the United States with an $50 billion alleged Ponzi scheme run by Bernard Madoff.”

The report adds that the impact of these schemes is much higher in countries with weaker regulatory frameworks.

Among the recommendations listed in the report is the advice that officials need to move in quickly and decisively.

“The longer that they operate, the more damage they are able to inflict,” the report states.

“Thus, the main policy lesson that can be extracted from countries’ experiences with Ponzi schemes is the need for a rapid and early response from financial regulators and law enforcement authorities to identify and stop the schemes and protect investors’ interests. However, responding swiftly has proven to be a challenge in many countries.”

Some countries have heeded this advice by enacting pyramid scheme bans and related legislation in recent years.

But while Jamaica’s ban is included in its securities law and carries a maximum penalty of 10 years in prison, the bans in Barbados, the BVI and Guyana fall under consumer protection legislation and carry relatively lighter penalties, with maximum prison sentences of no more than two years.

And even with pyramid bans in place, many experts see a need to reform financial services laws across the region. Existing frameworks, they say, often tightly regulate licensed entities but allow unlicensed ventures including pyramids to slip through the cracks.

“I don’t think we have many, or any, modern securities laws which protect the investing public from predatory promoters and sellers of investment securities in the Caribbean,” said BVI-based fraud attorney Martin Kenney. “I think that’s just one major hole we have in in public policy.”

Dr Stacie Bosley – an economist at Hamline University in Minnesota who studies pyramids schemes – said she has seen a similar problem in the US: Larger schemes carried out by licensed entities, she said, are more likely to draw the attention of regulators.

“I think on the other side, we also have to address the low-hanging fruit here, which are the pyramid schemes that are in our lives constantly and in plain sight,” she said.

The BVI is among the jurisdictions that have struggled with such issues, according to Mr. Penn, the FSC director of enforcement.

“Sometimes you see [scams] in the form of regulated activity, but just with pyramid-type characteristics, and in those cases, regulators would be able to go after them because of breaches of the financial services legislation as relates to that specific investment activity,” Penn said.

“On the Ponzi or pyramid schemes that we’ve seen in the BVI, it won’t get caught by our Securities and Investment Business Act, because effectively they’re not investments. None of them are structured as investments, and investments have some very specific definitions and characteristics under our securities and investment business law,” he added.

Penn argued that legislation allowing for recouping stolen funds would be particularly useful in the BVI.

“Prohibiting, fining, jail time: They’re all within the realm of prohibition,” he said. “But I believe the real teach would be if you’re able to go to recoup those funds and effectively disgorge and repay the persons that have been defrauded. So that that would probably be one element that I’d like to see.”

Kenney said that countries around the Caribbean might look to the United Kingdom for a solution to such issues, enacting civil-asset-recovery laws like Britain’s Proceeds of Crime Act.

“It’s much easier in theory to recover proceeds of crime than it is to put the guy in jail,” he said. “That’s why we call it civil asset recovery as opposed to the old-fashioned criminal asset forfeiture, which does require a criminal conviction before you can trigger recovery.”

He added, though, that the small size of many Caribbean countries also means that enforcement and legislative capacity can be limited.

Efforts at legislative reform, however, might have to overcome resistance. FitzPatrick believes pyramid frauds have flourished largely because of the protection of laws designed to legitimise so-called “multi-level-marketing” (MLM) strategies.

MLM – which he said first appeared in the mid-20th Century in the US – uses direct selling to market various products.

Some MLM businesses earn money primarily from the products they sell. But FitzPatrick said many others effectively operate as pyramid schemes, earning mostly from recruiting salespeople who are required to purchase questionable products in order to join.

“There had never been a pyramid scheme attached to a business,” he said, adding, “I mean, there was gambling; there were lotteries; there were numbers rackets and things like that. But no business that claimed legitimacy based on an endless chain. And multi-level marketing was the first actually for that to occur.”

In part because of their lobbying efforts, MLMs managed to flourish despite successful prosecutions in their early days, and today they are a multibillion-dollar industry operating widely across the US and further abroad.

But FitzPatrick said more than 99 percent of the five million Americans who join pyramid sales schemes each year lose their money, and their failure is often blamed on their purported lack of hard work.

“So, I compare the product (sold through pyramid-based MLMs) to being like cheese on a mousetrap,” he said.

“If you tell the mouse about the cheese — talk about the cheese: good cheese, Cheese Whiz, vintage cheese — it wouldn’t help him very much. You need to tell him about this device the cheese is sitting on. Nobody tells the mouse about that. They only hear about the products and all like that: Then they get in and they discover they’ve actually been lured into a financial trap.”

“It’s not just that you’re taking on a potential risk for yourself, you’re taking on a risk and literally actively passing that risk on to other people.”

Dr Bosley, Hamline University Professor

But pyramid-based MLMs are nevertheless lucrative for those at the top, who FitzPatrick said have successfully lobbied for laws that help them stay in business. Those laws, he added, often take the form of “anti-pyramid” legislation that distinguishes between MLMs and “pyramid” schemes.

“Here and there, the (US Federal Trade Commission) goes out and prosecutes one to make it kind of look like they’re doing something,” he said. “But overall, the scheme enjoys the power and the backing of the (US) government. They have a 44-member caucus in Congress to sort of protect them. They’re endorsed by the Chamber of Commerce, the Better Business Bureau.”

The anti-pyramid lobby, on the other hand, is far less powerful, he added.

“The victims themselves are largely voiceless, unorganised, and mostly silent politically,” FitzPatrick said.

This situation, he said, makes it more difficult even to prosecute old-fashioned pyramid schemes with no product attached, like those that have proliferated recently across the Caribbean.

In response, he said, stronger laws are needed, but education is important as well.

“It’s obviously a powerful force in the economic world, but nobody talks about it,” he said. “So, there’s very little public education about such things.”

Other experts and regulators also have stressed the importance of educating the public about pyramid schemes.

“I think this is a case of people not being educated financially,” said Leslie-Ward, the Barbados regulator.

“This situation has taught me the approach taken in educating the public is an important tool for getting people to understand the defects of pyramid schemes. We realise we have to regroup and educate them on how finances work.”

Dr Bosley, the Hamline University professor, suggested that education campaigns might be retooled to focus more on the risk to family members, friends and others who are drawn into the frauds.

“It’s not just that you’re taking on a potential risk for yourself,” she said. “You’re taking on a risk and literally actively passing that risk on to other people.”

Focusing on such collateral damage, she said, has been successful in discouraging smoking in recent decades.

“We were able to sort of win the public’s heart a bit more on smoking when they had to think about the impact of smoke on their children in the car,” she explained. “I think that can be a more powerful emotion and might be more powerful in interrupting this.”

Dr Bosley also suggested pressuring social media companies to do their part to discourage the spread of their frauds.

“We need to make sure we’re putting pressure on them to interrupt disinformation campaigns,” she said. “There should be some pressure or incentive or resources to interrupt the fraud campaigns that are on our social media.”

Authorities engaged in the current epidemic of financial fraud of this kind appear hopeful that a combination of public education and awareness, together with enlightened laws and regulations, can bring about a significant change in the region’s vulnerability to such practices.