Talia was struggling to make ends meet as a bartender in Santiago, Cuba, when a friend told her about a lucrative job opportunity in Suriname.

The 26-year-old mother — who asked to be identified by a pseudonym to protect her privacy — had never heard of the Dutch-speaking country nearly 2,000 miles away.

But the promise of a job that would help her provide for her family was too much to ignore. Santiago is Cuba’s second largest city and the home of Bacardi rum, but Talia said it offered few prospects for her: Wages there are low, and many people live without consistent running water or electricity.

Her friend introduced her to the man who would arrange her trip. All she had to do was borrow US$1,000 from him for the plane ticket. Repayment would be easy, he said, claiming that the Surinamese government gives away thousands of dollars every month in social services.

With high hopes, Talia accepted the deal. But when she got to the Surinamese capital of Paramaribo last November, the bartender job she had been promised didn’t materialise. Instead, her employer confiscated her passport and forced her into sex work. She earned US$50 per client, but her captors kept most of the money to cover her rent, giving her barely enough to buy meals, she said.

“I want to tell everyone who is thinking of trying to get a job under these circumstances, don’t do it, please,” Talia told the Caribbean Investigative Journalism Network (CIJN).

After she had spent about two months in Suriname, another victim escaped and reported their situation to the country’s Trafficking in Persons Unit. As a result, the authorities raided the establishment where Talia worked and freed her and 14 other victims.

“After I was rescued by the TIP Unit, I was able to contact my parents and my son, and they were so depressed hearing my story,” she said. “My father wanted to come to Suriname immediately.”

Talia’s experience was a textbook case of sex trafficking, a type of modern-day slavery, and it is not unusual in the Caribbean. Though the region’s leaders and law enforcers often downplay the prevalence of human trafficking in their countries, researchers say the problem is widespread and may be exacerbated by a post-pandemic boom in online recruiting.

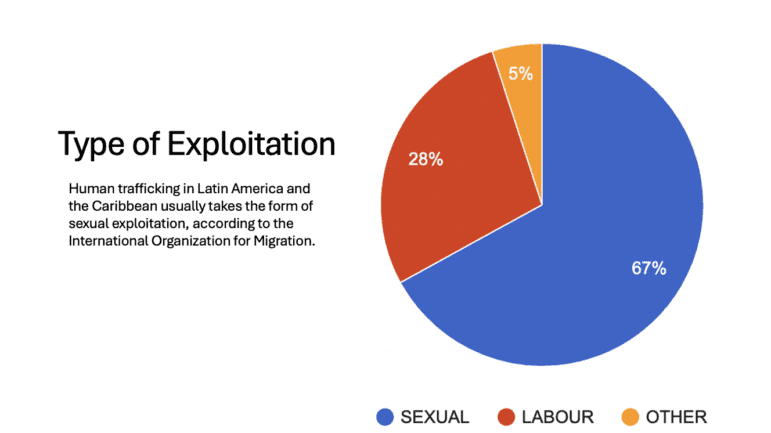

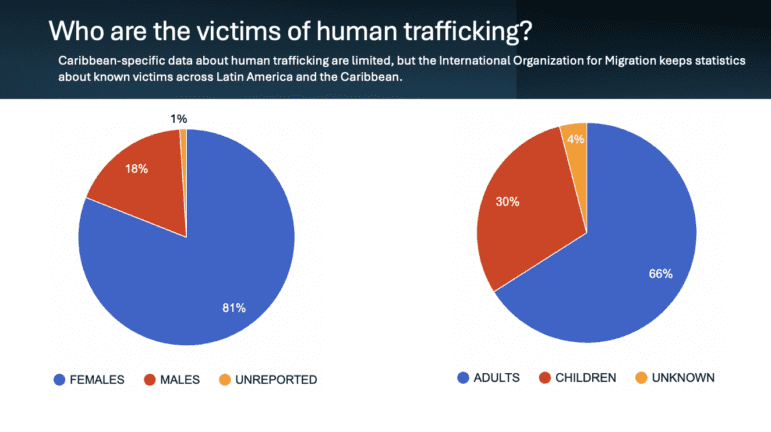

Most victims are women or girls who are trafficked for sex work, according to the United Nations-affiliated International Organization for Migration (IOM).

Like Talia, they are frequently tricked by criminals who take advantage of their desire to escape poverty, especially in struggling countries like Cuba, Venezuela and Haiti.

“Victims, generally, are often lured by false promises of employment or better living conditions,” said Zeke Beharry, a project manager at the IOM’s office in Barbados. “It can be a lack of better opportunities for education and then they find themselves in situations where they are exploited in various industries, and this can be not just the sex industry, but it can be for agriculture, for construction, for domestic work.”

Beharry said the effects of human trafficking — which he defined as “a severe and pervasive issue involving the exploitation of individuals for forced labour, sexual exploitation, or even other forms of abuse” — don’t stop with the victims.

“The socioeconomic impacts of trafficking in persons are profound,” he said. “It disrupts the communities, it perpetuates poverty, and it undermines economic development.”

Two-decade crackdown

Human trafficking is not only a Caribbean problem. It is a global problem. And at a 2000 United Nations meeting in Palermo, Italy, world leaders agreed to work more closely together to fight such transnational crime.

One result was the UN Protocol Against Trafficking in Persons, which took effect in 2003 and has been signed by 117 countries that have committed to broad-ranging anti-trafficking measures.

Around the time the protocol was agreed, the United States also launched a related initiative: its annual Trafficking in Persons Report, which ranks countries each year on a three-tier system based on their compliance with the US’s own anti-trafficking legislation.

Since then, most Caribbean countries have come on board, signing on to the protocol and taking related steps such as passing anti-trafficking laws and setting up special units to fight the crime.

Today, they mostly rank on Tier Two of the US list, meaning they have not yet met the US standard but they are working toward it. Exceptions include Suriname, the Bahamas and Guyana, which are now on the fully-compliant Tier One list, while Cuba, St. Maarten and nearby Venezuela are categorised as Tier Three non-compliers subject to sanctions and funding restrictions. Haiti received a “special case” classification this year because of its ongoing political turmoil.

As Caribbean governments work to meet global standards, they sometimes cite their progress to suggest that they are winning the fight against sex trafficking and related crimes.

But researchers and victim advocates told CIJN a different story. Though they tend to support the global crackdown, they said the policies and laws it has brought to the region haven’t always been effective. Funding is limited and prosecutions are rare, they noted, adding that corrupt law enforcers sometimes help facilitate the trade.

Meanwhile, sex-trafficking continues to flourish in the region, often by hiding in plain sight, according to researchers.

“The full scope of human trafficking in the Caribbean has proven very difficult to measure,” US-based human rights scholar Gabrielle McKenzie wrote last year in a study published in the Journal of Global South Studies. “Despite the prevalence of the crime, there is relatively little documentation of trafficking statistics compared with other regions of the world. Underreporting by law enforcement officials and a lack of Caribbean-specific efforts to collect data on the issue both contribute to this problem.”

Citing “anecdotal evidence,” the study suggested that “widespread” trafficking in the Caribbean is exacerbated by factors including the sex-tourism industry, a history of human enslavement, and a shortage of funding to enact meaningful reforms.

‘I’m doing this because I’m in love’

CIJN journalists in five countries made similar findings during the course of this investigation.

In Suriname, Talia’s story ended on a positive note: After she was rescued by the authorities, she was permitted to stay in the country. She now works as a hairdresser, and is hoping to bring her 5-year-old son to join her.

But an advocate for sex workers in Suriname described a flourishing sex trade where people as young as 14 are exploited by a dangerous underground industry.

“A lot of sex workers don’t even know what is trafficking,” said Denise Carr, the executive director of the DCF SUCOS sex-worker collective in Suriname. “So how can they explain that ‘I’m being trafficked’? They see it like it’s a normal thing. Okay, maybe if their boyfriend is, like, taking their money: ‘Okay. It’s my boyfriend. I love him. I’m doing this because I’m in love.’ But they don’t really have the idea that this could be trafficking.”

Because prostitution is illegal in Suriname, she added, victims often fear they would be exposed to further victimisation if they turned to the authorities for help.

“You wouldn’t get sex workers to open up and say of their challenges, because historically no one listens to us and we are being criminalised,” Carr said.

Dr Joan Phillips, a sociologist based at the University of the West Indies’ campus in Cave Hill, Barbados, said Caribbean sex-traffickers often rely on extensive informal networks that facilitate the sex trade across the region.

“There is a network which is facilitating women’s entry into sex work, and sometimes more vulnerable women into sex trafficking,” Phillips said.

In the case of Barbados, she said, women have been brought from countries including Guyana, Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, and St Vincent and the Grenadines.

Such networks can function as a “hidden system of exploitation” because few trafficking victims come forward to report the crime — or even to discuss their experience after they’ve been rescued, according to the researcher.

“The link between sex work and trafficking makes it more difficult to find women who have been sex trafficked, because a lot of the women who are deported were seen as sex workers rather than having been trafficked,” said Phillips, who wrote her PhD thesis on men who solicit sex on the beaches of Barbados. “And what happens is the government, the police, take these women and just deport them as a solution to the problem of sex trafficking.”

Though the victims may willingly travel to another country to work, most are first deceived about the terms of their employment, she explained.

“Nobody makes a decision to migrate under suspicious circumstances,” she said. “They might come and then their passports are taken away.”

In Trinidad and Tobago, a hotspot for sex-trafficking from neighbouring Venezuela, volunteer Allan Balfour has seen the crime’s effects firsthand. Among the victims in his country are minors who have been so traumatised they went mute, he said.

“When it’s time for rescue, you will see a 14-year-old who’s pregnant and or they might have had a child already for their captor,” Balfour told CIJN.

In Belize, as in other countries, many victims of sex-trafficking are migrants seeking employment that will allow them to send money back home, according to Jaunna Murrillo, the National Coordinator at the country’s Anti-Trafficking in Persons Council.

But she said officials are also seeing an increase in minors trafficked by family members within the country.

Prosecutions are particularly rare in these cases because the children “struggle with the thought of having to take their families to court or testifying against family,” Murrillo said.

‘Twisting’ information

In Antigua and Barbuda, traffickers routinely try new tactics to stay ahead of authorities, according to Alverna Inniss, the Care and Support Services Coordinator at the Trafficking in Persons (Prevention) Unit within the country’s Ministry of Public Safety and Labour.

“They are using the very information that we give to the general public, and they are twisting it,” she said. “In order to ensure that the same young ladies don’t go and make any sort of a report, they tell them that if they do so they are going to be charged for working, because you have to be in the country over X time before you work. And if you do work, you must get a work permit. Remember, the women don’t know.”

For similar reasons, she said, many traffickers have also stopped confiscating passports — now a well-known warning sign — and turned to intimidating their victims instead.

“Seemingly, they are free to walk, but then they have persons who are watching what they are doing, who they are talking to, and where they are going,” Inniss said.

Some victims are also forced into becoming recruiters.

“They may know you have children,” she said. “They know you have siblings and whoever it is, and they threaten them. So they are likely to do it.”

From Jamaica to Antigua

Tameika Blackwood can relate to such threats. Today, she is a successful nail technician living in Antigua. But in 2008, she said, she was a single mother working at a bar in her native Jamaica, and the court had awarded custody of her only son to his well-off father because she was homeless.

A group of male regulars at the bar told her she could make a lot of money working at a bar owned by one of the men’s aunts in St John’s, Antigua.

She didn’t have a passport, so they provided one and instructed her to start using the name it contained. The forgery, she was told, cost around US$200.

The day she left Jamaica, a police officer at the airport pulled her out of the check-in line for questioning.

“They already gave me details what I am to say, so I told the police officer I am going to a family member,” Blackwood said. “The officer let me go back in the line.”

When she landed in Antigua, she and another woman travelling with her were taken straight to work.

“They take our suitcases and carry around the back,” she said. “I see a lot of girls half naked, and men in the yard also. Me and the young lady got a room together.”

The woman who brought them from the airport told them they would have to pay EC$100 (about US$37) in rent every Friday.

“She then call us back and said we must pick our costume. I said, ‘Costume?’ A lady was showing us G-strings. I said, ‘I not putting on any of that stuff. I did not sign up for that!’ So the woman came inside the room and said I have to dance on a pole.”

For more than a month, she said, she refused to work as a prostitute or exotic dancer. She spent her days crying in the club, barely eating or drinking. A man took pity on her and sometimes bought her food, but the owner eventually decided to send her back home, calling her a “waste of time” who didn’t make money. Her return ticket was another cost added to her growing bill.

When she reached home, she was met by the bar owner’s nephew, who had recruited her.

“I said to him, ‘You trick me!,’” she recalled. “‘You make me go off to something wha’ I never planned to do. I never even been in a strip club!’”

But he was unrepentant, and he told her that she owed them money for the trip to Antigua and back, the fake passport, and her room and board while there, she said. He also said she would be killed if she did not repay the debts, according to Blackwood.

She was terrified. She thought of hiding in the countryside, but a friend in Antigua — the same man who took pity on her in the bar in St John’s — suggested she return to the island instead. He paid for her flight, and within six months she was pregnant with his child.

He soon abandoned her, but while her daughter was still an infant she went to the Directorate of Gender Affairs, now called the Bureau of Gender Affairs. It was the start of the long and arduous process to regularise her status in the country.

What’s next?

The UN protocol focuses on a “four P” approach to addressing human trafficking: preventing the crime by raising awareness; protecting and assisting victims; prosecuting perpetrators; and partnering with stakeholders across society.

Such principles also help guide the annual US report.

“We work very hard at this report; it constitutes information from 188 countries,” said Kamesh Chivukula, a Political Officer at the US Embassy in Belize, adding, “This is not a comparison between countries. It’s a comparison of the country against its past performance.”

The assessments, which use criteria established by the US Congress, also cover the US itself, Chivukula told CIJN.

“By giving a Tier One, it doesn’t mean that the country doesn’t have any human trafficking,” he added. “What it really means is that efforts are being done in general and the standards are being met.”

Caribbean researchers and victim advocates told CIJN that the US-led approach has brought positive progress in the region, but they also said more is needed. Meanwhile, the US-led approach itself has been facing increasing scrutiny.

“Recent efforts to fight trafficking in the region include legislative and policy initiatives,” McKenzie, the US-based scholar, wrote in her 2023 study. “Unfortunately, some of these efforts are flawed insofar as they are based on Western models, with relatively little input from stakeholders in the region. Evidence suggests that these efforts, while admirable, fail because they are not sufficiently nuanced to capture and address the socioeconomic and cultural causes of trafficking in the Caribbean.”

Rather than using a one-size-fits-all approach, she suggested that Caribbean countries need to collect more data and develop a regional strategy to combat trafficking crimes. As a starting point, she recommended a wide-ranging survey of survivors, victim advocates, scholars, government actors and other stakeholders in the region to better assess the extent of the problem and decide the way forward.

Alana Wheeler, the former Director of the Counter Trafficking Unit in Trinidad and Tobago, offered similar ideas.

“I would want to see a more increased understanding of the seriousness of trafficking in persons among the policymakers and the decision-makers and those who are implementing the law,” she said.

She added that her country has been focused largely on meeting the US standards, but a broader effort is needed across society.

“We need to address this ill not just to meet a tier ranking, but we need to address this ill because it’s inhumane, it’s evil and it’s wrong,” she said.

In Trinidad and Tobago, she added, women are often seen as sexual objects, and the appetite for pornography is high.

“It is culturally accepted that men go to certain places in our country to enjoy the sexual services that women offer,” she said.

Such attitudes help sex-trafficking to flourish, according to Wheeler.

Balfour, the Trinidad volunteer, has used dance to raise awareness about the problem and push for change.

Working with Terry Springer, who also volunteers in the migrant community, he recently co-choreographed the Trinity Dance Theatre’s 2024 performance “Silenced,” which is based on human trafficking and gender-based violence.

Legalise it?

Others push to fully legalise prostitution, pointing out that many sex workers operate in an unregulated industry with limited protection.

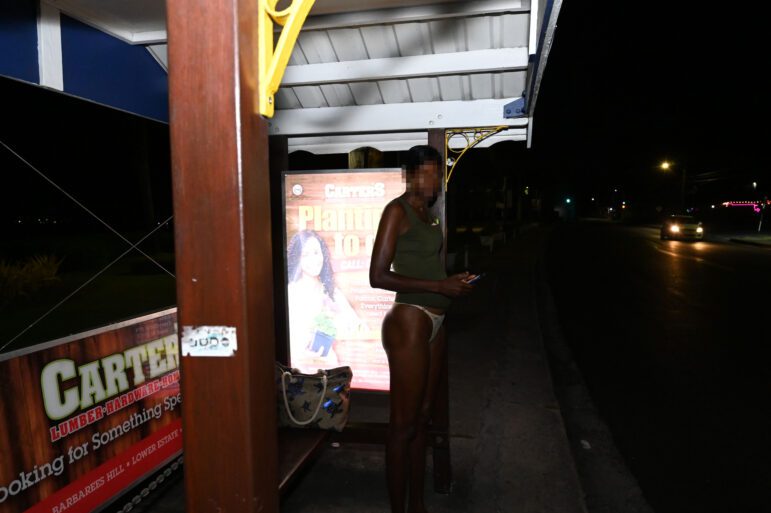

A case in point is Melissa Narcisse, a 34-year-old sex worker in Barbados. Narcisse does not consider herself a trafficking victim, but she said she was pressured into sex work by her two friends and one of the fathers of her children, who told her, “Oh, Melissa: It making money, it making money, it making money.”

On a rainy Wednesday evening in St Michael’s, Narcisse stood in a bus shed near Prime Minister Mia Mottley’s official office. She was dressed only in a vest and underwear, and she was seeking male customers.

“I don’t like this life. I’ll be straight with you all,” Narcisse told CIJN.

Safety is a constant concern. Narcisse said she has been raped, robbed and assaulted while plying her trade. Once, she recalled, she was chopped in the back with a cutlass, and even then the police did not take any action against her attacker.

But she has seven children to feed and she can make between BBD$600-$1,000 (about US$300-$500) a night.

“I come out here for a reason,” she said. “I doing this because I want house and land. I get house and land and a proper place to live, I done with this sorta life.”

Advocates for fully legalising sex work and related activities argue that the unregulated industry leaves workers vulnerable to trafficking and other exploitation.

Among these advocates is Charles Lewis, a former escort and current head of the Adult Industry Association in Barbados.

Lewis, who goes by “Charlie Spice,” argues that legalisation would help eliminate stigma and make police officers more responsive to victims like Narcisse.

“As a result of being criminalised, it drives the industry more underground,” he said. “And when it goes underground, it is hard to control the issues that stem from it, like the health issues, the criminality issues, social issues.”

Some law enforcers agree, including Letitia Pinas, who heads the Trafficking in Persons Unit in Suriname.

“When you legalise prostitution, you can better regulate and punish if they don’t adhere to the law,” said Pinas, who was recently named one of the US Department of State’s top ten “TIP Heroes.” “But I don’t have the feeling that the Surinamese government wants to legalise prostitution.”

Inniss, the TIPS officer in Antigua, said that reducing stigma by legalising prostitution would also help sex workers access better health care.

“We have had persons with STIs and infections and so on,” she said.

Phillips, the Barbados researcher, supported legalisation as well, but she also called for much broader reforms to support vulnerable women in the Caribbean.

“The government needs to support the Trafficking in Persons Unit,” she said. “We need more information. We need more research. We need more attention given to these vulnerable women in society. And it is because, you know, they’re harassed; they’re exploited. They need a helping hand.”