Survivors of sexual assault in Antigua and Barbuda endure a long road to justice.

The childhood of S was shattered at age 6 when her father began a cycle of sexual abuse.

The abuse escalated, resulting in her pregnancy at 15 years old. Now 26, S (the initial of her first name) is mother to a 9-year-old daughter, a child born of unspeakable circumstances. S and her daughter share the same father.

For two decades, S’s pleas for help were ignored. But in 2021, a spark of hope ignited when her father was charged with incest. S described the years of abuse as the “worst thing to ever happen” to her.

In April, 2024, S’s father pleaded guilty to four counts of incest. The man, who is in his early fifties, had sex with her on several occasions– including during her pregnancy and while she was healing from childbirth. He is being held at His Majesty’s Prison in St. Johns. His sentencing hearing has been adjourned three times to give his attorney more time to examine pre-sentencing reports.

S expressed frustration with having to relive her trauma for the last 20 years

“At some point I began to lose hope,” she said. “I was thinking that maybe he had some police officers in his pocket or maybe a politician because why did it take so long? I just wished someone had told me I would have had to tell my story [so many] times.”

Statutory Rape is Prevalent

Antigua and Barbuda, like much of the Caribbean, is grappling with high levels of sexual violence.

A recent survey of “Women Visiting Public Health Clinics for Antenatal, Postnatal, and Family Planning Services in Antigua and Barbuda, conducted by medical professionals from the region, revealed that sexual activity of females sometimes begins before age 10, with 29 % of victims experiencing it by age 15. That qualifies as statutory rape.

According to the United Nations Regional Human Development Report in 2021, Latin America and the Caribbean region is struggling with high levels of sexual violence, femicide, and violence towards children.

The report highlights that the region “has the third highest lifetime prevalence of sexual violence perpetrated by non-partners and the second highest rate of violence perpetrated by partners. Violence against [children] is also among the highest in the world.”

For victims of sexual crimes in Antigua and Barbuda, seeking justice can seem like a nightmare that never ends. The lengthy legal process means that they have to relive their trauma at each stage in the proceedings.

A Failing System

S, now a mother of two, said she felt the police had an aggressive tone in their questioning. “At one point I just thought that they thought that I was lying,” she shared.

S made several attempts throughout her childhood to stop her father from abusing her. His crimes only came to light when S applied for child support, causing the court to order an investigation into her situation.

Even after that, financial or psychological help was hard to come by.

“There were not many support systems or resources that were helpful during this legal process…I count on my fingers how many times I’ve gotten help,” she shared.

Obstacles to Justice

The Director of Public Prosecutions’ office disclosed that one of the challenges facing prosecutors is the lack of DNA analysis in sexual offence cases.

“There has not been DNA analysis in sexual offences in several years despite rape kits being done,” stated the DPP’s office in a written response to questions from the Caribbean Investigative Journalism Network.

The government has been working towards establishing a forensic lab so that DNA testing can be done on the island, instead of neighbouring islands.

A recent development could make it more difficult for some victims. Antigua’s legislators have eliminated the so-called “recent complaint” doctrine, which had allowed victims’ reports– made soon after their sexual assaults– to support their credibility.

S expressed doubt about achieving true justice.

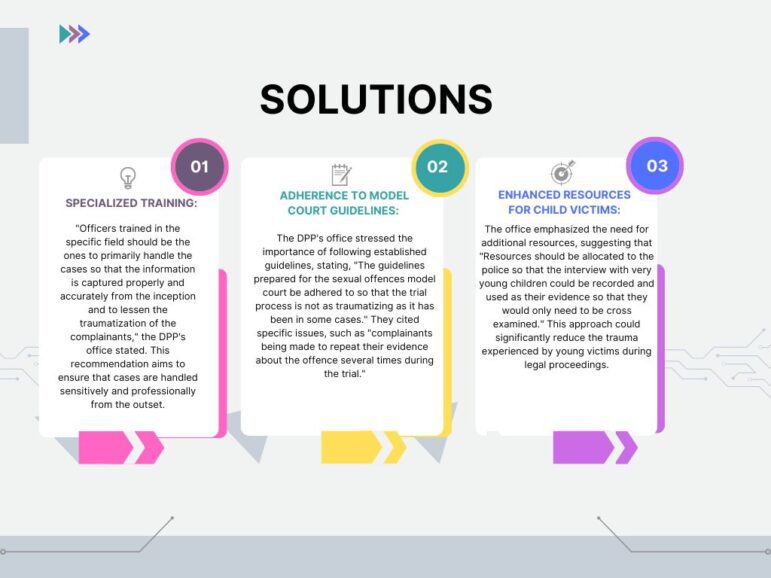

The Director of Public Prosecutions’ (DPP’s) office has proposed several recommendations to improve the handling of sex crime cases. These include specialised training for officers, increased support for child victims, and measures to make courtroom proceedings less traumatic for young victims.

The Numbers Bring Hope…and Concern

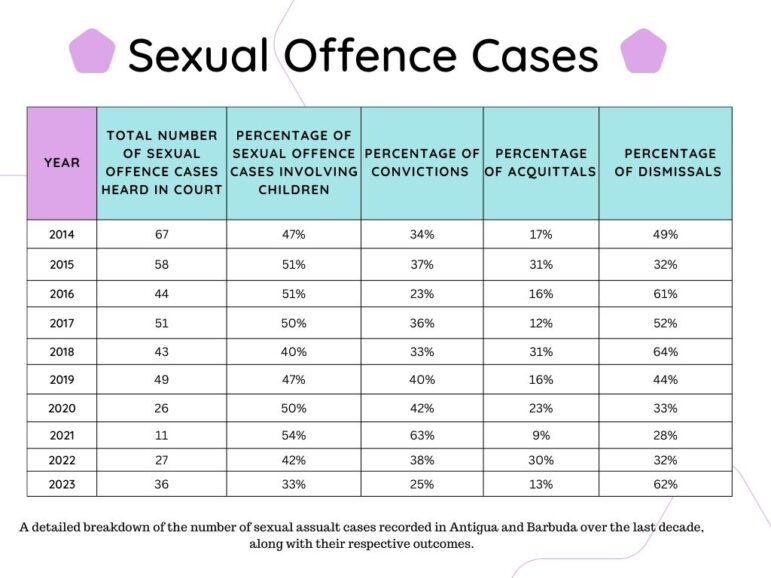

Statistics from the office of the Director of Public Prosecutions tell a story that can be interpreted as both encouraging and concerning. There has been a general decrease in the number of sexual offence cases being heard in court in the last 10 years.

In recent years, the number of cases dismissed against men accused of sex crimes has soared, according to the DPP’s office. In 2023, a whopping 62% of cases were dismissed. That’s the second-highest dismissal rate in the decade, a tick behind 64% in 2018.

“Approximately 80% of the dismissals were as a result of persons no longer wishing to proceed with their matters,”the DPP’s office stated.

According to the office, these cases do not proceed due to various factors:

- Time lapse since the offence occurred, leading to reluctance in recounting details after many years.

- Survivors feeling too traumatised to relive the events in court, often fearing disbelief.

- Complainants who have relocated and cannot be located.

- Instances where the accused has passed away before the trial.

Addressing the Problem

Counsellor Koren Norten, a mental health professional, highlighted the severe psychological toll of drawn-out legal processes. She likened the effect of judicial delays on traumatised victims to “having an open wound that’s never healing.”

Recognizing the complex needs of sexual assault survivors, Norten outlined a comprehensive approach to victim support.

She emphasised the significance of empowerment, breathing exercises, community support, and other vital elements in their recovery.

She said a client whose case kept getting postponed had difficulties in focusing, maintaining relationships, engaging with partners, and experiencing panic attacks.

“The legal system needs to consider the implications waiting can have on the victim,” Norten said. “People will not come forward and tell their story if there’s this long wait, because they feel like, what’s the point?”

She called for closer collaboration between law enforcement, hospitals, and the gender affairs department to ensure psychosocial support for victims.

“Something has been taken from somebody who has been sexually assaulted,” Norten said. “We have to work together as a society to help them to regain some level of normalcy.”

Marsha James-Pharoah, Deputy Director of Family and Social Services, said although her department offers counselling services, they are not available until after legal proceedings end. Counselling is typically mandated by a judge’s order.

“In numerous cases, counselling has empowered victims to testify,” James-Pharoah said. “ It’s transformed their fear of recounting the incident into courage.”

James-Pharoah said mandatory early intervention is needed to help victims of sexual assault. “Implementing support services from the outset would not only help victims feel more at ease sharing their experiences,” she said, “but it would also ensure they [would have] made significant progress in their healing journey by the time legal proceedings conclude.”

This approach, she said, could significantly improve outcomes for victims and the justice system alike.

Programmes and Solutions

Antigua and Barbuda has taken significant steps to address sexual offences through the establishment of a Model Sexual Offences Court.

Minister of Legal Affairs Sir Steadroy Benjamin reports that this court was created with the goal of resolving sexual offence cases within 18 months.

“It has worked extremely well, and all of the persons involved in these matters are satisfied that justice is being done quickly, fairly, and so that persons can have these matters dispensed with quickly,” Benjamin said. He acknowledges that with any new initiative, “there will be weaknesses” and that they are “looking at ways and means to see how we could improve the system.”

In addition, the DPP’s office has recently established a Victim Care Unit “where the aim is to keep complainants informed of the status of their matters from the time matter gets to the office.”

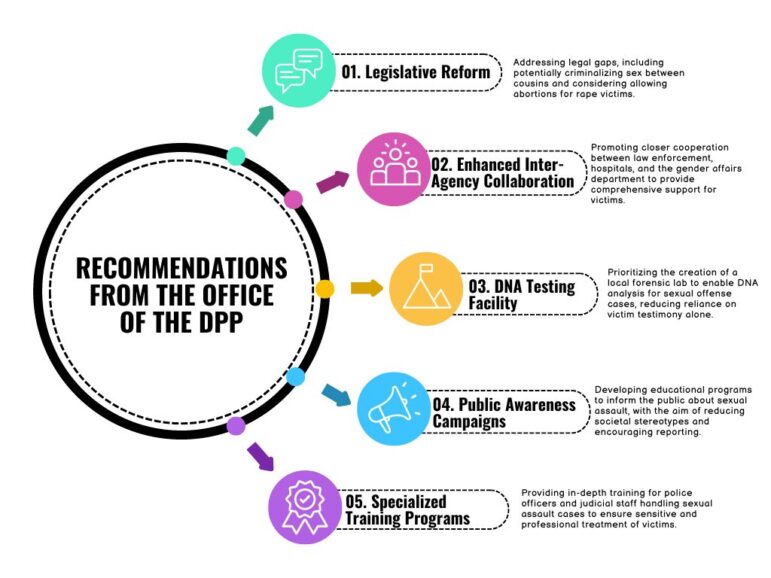

However, there is still much room for improvement. To combat sexual assault one can, for example, implement legal reforms, enhance inter-agency collaboration, and establish a local DNA testing facility, all aimed at improving victim support, increasing reporting rates, and strengthening the justice system’s response to sexual offenses.