For the people of Suriname, offshore oil is supposed to be a game-changer.

As they have struggled through a protracted economic crisis over the past decade, they have watched lucrative deep-water discoveries transform neighbouring Guyana.

They have also heard their own leaders promise that a similar oil boom will come soon to Suriname, bringing badly needed jobs and wealth for the country’s more than 600,000 people and helping resolve a debt crisis that recently led to riots in the capital.

But the people are still waiting.

The Final Investment Decision for Suriname’s first deep-water drilling project has been deferred repeatedly, and mounting frustration with the delay has highlighted the secrecy surrounding the nascent industry.

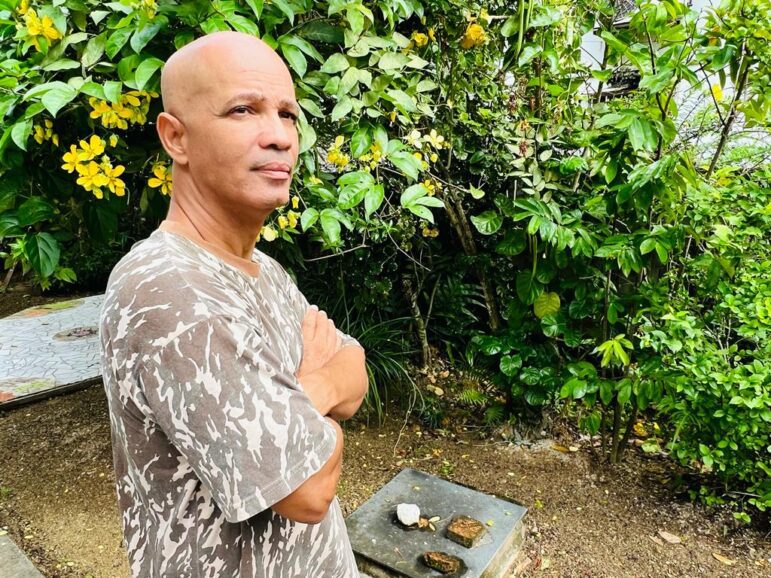

“We should at least know what kind of contracts have been made, and don’t come up with stories that it’s confidential between us and [foreign oil companies],” Surinamese environmentalist Erlan Sleur told the Caribbean Investigative Journalism Network. “That is, of course, the greatest nonsense. That means that there are things in the contracts that you don’t want to have to come out. And it is in the national interest, so all transparency is served by that — especially when you know that there is already so much corruption in our country.”

In Suriname, oil bids are conducted largely in secret; oil contracts and other documentation are kept from the public despite more than six years of government promises to publish them; and freedom-of-information legislation has been delayed for more than a decade.

The national oil company, Staatsolie, told CIJN that it is working to improve transparency and that its bidding processes and contracts are already up to international standards. Similar promises have also come from Suriname President Chandrikapersad “Chan” Santokhi, a former police commissioner who took office in 2020 pledging to reform the corruption that has long plagued the country.

“If you want to get maximum benefit from oil and gas exploration, there must be a few preconditions in place, such as responsible, transparent and fair governance,” Santokhi said in March 2022. “Through good policy, the right development of these sectors can make all Surinamese and the country rich.”

But transparency advocates fear the emerging offshore oil sector could fall into a trap that has plagued other extractive industries in the country.

Without access to contracts and other basic information about the sector, they say, the public is unlikely to see the promised social and economic progress from any oil boom that does materialise. Instead, they fear the country could succumb to the “natural resource curse” that has plagued oil-rich countries like Venezuela, where corruption has empowered a tiny elite to plunder the profits from public resources while the wealth gap has expanded dramatically.

Guyana transparency advocate Frederick Collins warned of signs that a similar story may be starting to play out in his country as offshore production has soared in recent years.

“These guys play games with the people’s resources all the time,” said Mr. Collins, who is president of Transparency Institute Guyana Inc (TIGI), a local affiliate of Transparency International, adding, “Hopefully, Suriname will never allow itself to fall victim to that kind of nonsense.”

The Wealth Next Door

In Guyana, the offshore boom started in 2015 when United States company ExxonMobil struck oil in an area known as the Stabroek Block.

Since then, the country has reaped big pay-outs as oil companies have found more than 10 billion barrels of recoverable oil and gas in its underwater reservoirs.

Guyana’s oil exports more than doubled last year — from about 101,000 barrels per day in 2021 to nearly 266,000 — and the country hopes to boost production four-fold by the end of the decade.

The government’s revenue from oil exports and royalties has followed suit, climbing from about $409 million in 2021 to some $1.1 billion last year. This year, it is expected to climb 31 percent more, to $1.63 billion, Finance Minister Ashni Singh said recently during his presentation of Guyana’s 2023 budget.

As a result, despite activists’ warnings that many people are getting left behind, Guyana’s economy is now among the fastest growing in the world.

Boom or Bust?

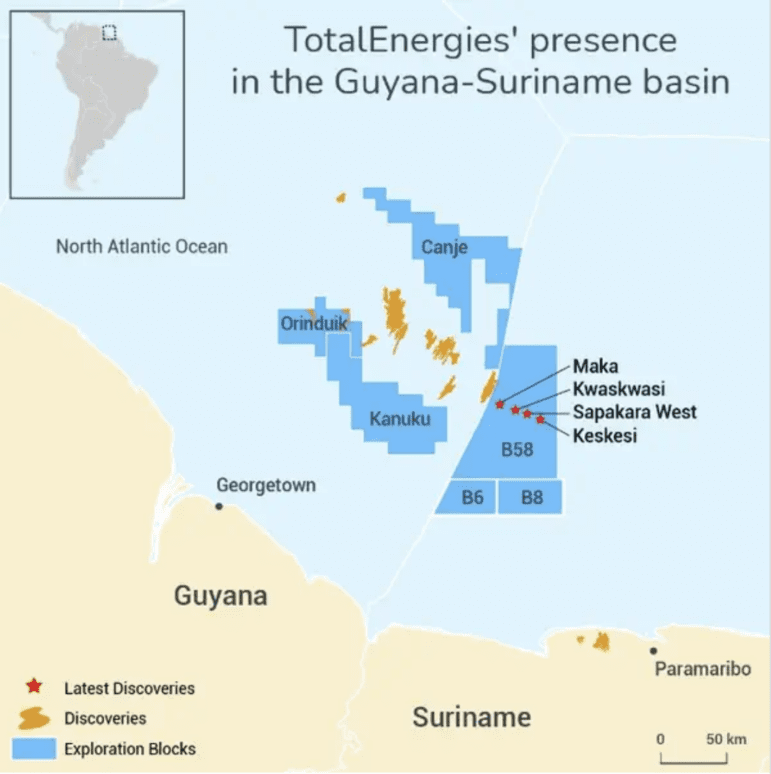

Suriname hopes to find a similar oil windfall in its own waters, which border Guyana’s, and exploration has been ongoing for more than a decade.

The country needs the money. For eight years, it has been struggling with an economic crisis that has exacerbated poverty and brought skyrocketing inflation. The Covid-19 pandemic made matters worse, and Suriname’s gross domestic product contracted almost 16 percent in 2020.

Since then, the country has defaulted on its foreign debt three times, and it has struggled to convince international creditors to restructure its debt load despite a 2021 loan deal with the International Monetary Fund.

On the streets, the people have felt the pinch of related austerity measures, including a plan to remove fuel and electricity subsidies at a time when the cost of living is skyrocketing.

In February, the resulting unrest led to anti-government riots that rocked the capital of Paramaribo for several days and climaxed with protestors storming the country’s parliament.

Leaders say that offshore oil could bring the badly needed funds to help alleviate the poverty at the root of the unrest.

Such hopes got a big boost in 2020. That January, the United States-based Apache Corporation and its French partner TotalEnergies announced Suriname’s first major deep-water oil discovery. The companies then launched a potential extraction project that officials said could earn Suriname billions of dollars, with production initially projected to start as early as 2025.

At the time, the discovery was believed to be an extension of Guyana’s “Golden Lane,” an offshore area currently producing about 375,000 barrels a day for a consortium led by ExxonMobil — which aims to triple that output over the next five years.

But the Surinamese project has stalled repeatedly as TotalEnergies and Apache have deferred signing the Final Investment Decision needed to jumpstart the country’s oil boom by moving from exploration to production. Now, production is not expected to start before 2027 at the earliest — two years later than originally forecast.

TotalEnergies, Apache and the state-owned oil company Staatsolie have blamed the delays largely on geological complications and disappointing early results from exploratory drilling.

In an interview with the news outlet ATV in March, Staatsolie CEO Annand Jagesar explained that the endeavour has been complicated in part by underwater mud layers not found in Guyana’s sandier reservoirs.

Nevertheless, he said, the FID could come any day, and he expects it by the end of the year at the latest. From that moment on, the companies are expected to make enormous investments, including building a floating production platform that will cost up to $2 billion, he said.

“As soon as they announce the FID, there will be no way back,” he said. “That’s why it takes time, and it is a very important decision for the partners.”

Meanwhile, he said, TotalEnergies has already invested $1.3 billion and Apache has invested $600 million in the project.

“If that isn’t commitment, then I don’t know what is,” he said.

President Santokhi has also downplayed the delays, at times even describing them as a benefit that will give the country more time to prepare for the expected offshore boom.

And his government, he said, is taking full advantage.

“The government will do everything in its power to bring together all stakeholders in the energy sector to stimulate an integrated approach,” Santokhi said on national television last December.

Training, he added, is already under way to prepare young people to work and invest in the oil and gas sectors, and many of the participants will have graduated by the time production starts in 2027 or later.

Sceptical

But some Surinamese believe there may be more to the story, and they complain of a lack of transparency surrounding the delayed FID and oil contracts.

Wilfred Leeuwin, a journalist and transparency activist who advises the board of the Association of Surinamese Journalists, said he is sceptical that drilling disappointments and geological issues are the only reasons for the delays.

The oil companies, he pointed out, could have ample reason to await the results of Suriname’s ongoing negotiations to restructure its debts. As part of those negotiations, he noted, private bondholders would likely pressure Suriname to include future oil revenues in any deal — and Suriname would likely resist.

This dynamic, he said, could motivate TotalEnergies and Apache take a wait-and-see approach.

“I think that the deferring of the FID by the oil companies has something to do with the fact that bondholders are pressuring Suriname to include the oil revenues in the restructuring deal,” he said. “They take this to put pressure on Suriname by extending their FID.”

If so, this wait may be nearly over: The Suriname government announced in early May that it had reached an agreement in principle with bondholders that includes compensating them from future oil revenues from the area the companies are exploring. The deal is subject to IMF approval by June 15.

Collins, the Guyanese transparency advocate, said he had similar thoughts as Leeuwin’s when he learned that the FID had been delayed during a period of economic turmoil.

“I must tell you that I’m a very suspicious person, and I don’t believe that the things are not connected,” he said.

Related speculation came in a recent column in the publication OilNow. Analyst Arthur Deakin suggested last October that the companies may have cold feet in part because of Suriname’s more stringent fiscal terms in its oil profit-sharing agreements compared to its neighbours like Guyana, coupled with its “multi-year double-digit inflation, debt defaults and political patronage.”

TotalEnergies, however, denied that the FID delays are linked to Suriname’s economic woes.

“These speculations are false and groundless,” a TotalEnergies spokesperson wrote in a response to CIJN.

The companies, she added, are awaiting the results from a final appraisal well to decide if the oil resources are sufficient for development.

“We will then decide the way forward,” she stated. “It has not been linked to Suriname economic situation or else.”

In the Dark

In recent months, however, questions about the delayed FID have also highlighted a broader lack of transparency surrounding oil and other natural resources in Suriname.

Often, Sleur said, such issues have had outsized ramifications.

“We have had numerous industries such as alumina, gold, timber, and these have delivered more than enough income for the state,” said Sleur, who is the chairman of the environmental non-governmental organisation ProBios. “But still the economy is impoverished. Generating huge amounts of money from the oil and gas industry will not make a difference and only make a negative impact on the climate. To prevent climate change, we need to look at other industrial sources like renewable energy.”

Though many countries still keep oil contracts secret, Collins said he finds the practice highly problematical, and he added that access to the contracts may help the Surinamese public better understand the recent delays.

“Generally, the default position ought to be that all information belongs to the people, especially information that has to do with natural resources,” he said. “If you don’t have that information being public, then what you have is a few people … [who] tend to want to use the secrecy to benefit themselves.”

He also described a power imbalance that he said is common when negotiating global oil deals.

“These multinational oil companies, the game they have been playing throughout the history of oil is one in which they believe that they can hold third-world countries under their thumb,” he said. “In more recent times, the information we have in Guyana fits a certain pattern: It is that these multinational companies get hold of our prospective politicians — I don’t mean when they are in power, but before they’re in power — and somehow managed to make arrangements with them. … And so these guys would have made commitments that we, the people, know nothing about.”

Unkept Promises

In the past, the Suriname government has committed to increasing transparency in the oil sector, but it often has not followed up with the promised action.

In May 2017, the country joined the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, a Norway-headquartered group of more than 55 countries that have committed to disclosing wide-ranging information about their extractive industries, including contracts, licences and other documentation.

Since then, the country’s progress has often been slow, and it was suspended from EITI for three months in 2019 for missing reporting deadlines.

Even before that, its 2017 report included a pledge to publish oil contracts and licences and to disclose beneficial owners of oil companies operating in the country. The pledge has been repeated in subsequent reports. But to date, the oil contracts still aren’t public.

When CIJN requested them in February, Staatsolie Corporate Communication Advisor Kailash Bissesar said they would be released in March. They weren’t, and in April Bissesar apologised for the delay and said they would be released “as soon as possible.”

TotalEnergies also declined to provide its contract, though it stated that it has supported EITI since 2003 and advocates for countries to disclose their petroleum contracts and licences.

“This position has been shared with Suriname’s authorities and the national oil company Staatsolie, but of course it requires the approval of all stakeholders,” the TotalEnergies spokesperson stated.

In the meantime, TotalEnergies and Staatsolie both directed CIJN to a model production sharing contract posted on Staatsolie’s website.

Staatsolie explained that the model shows the “standard text and format of the contract and discloses” its mechanism.

“Several internationally recognised independent comparison studies have revealed that our contract terms are up to or better than par,” the company added.

However, when asked to provide those studies and to clarify if the model contract is identical to the actual contract, the company didn’t respond.

Staatsolie also stated that it is working to stay in good standing with EITI, and noted that its last suspension was “short” and “temporary.”

“We are working hard to submit the reports for the next deadline by December 2023 and preparing for the coming validation in October 2023,” the company wrote.

List of Contracts

Until the contracts are released, the public must content itself with a list posted on Staatsolie’s website naming companies with which the country has 11 active production sharing contracts for offshore and onshore blocks.

But Sleur and Leeuwin said this list and the model contract do not constitute sufficient transparency.

Both also remain sceptical of Staatsolie’s commitment to publish its contracts in full. At most, Leeuwin predicted, Staatsolie will provide a summary of the production sharing contracts while citing confidentiality concerns to justify withholding the rest.

He added that Staatsolie officials have already laid the groundwork for such excuses with comments suggesting that the contracts include articles and amendments that require confidentiality.

Sleur spoke similarly.

“I think they will lift a corner of the veil,” Sleur said. “I now have experience with Staatsolie, and that experience stems from the oil spill we had on the Suriname River last October.”

At the time, Sleur and ProBios publicly accused Staatsolie of causing the spill, but Staatsolie denied the allegation and sued to force them to retract. The court, however, ruled against Staatsolie, noting that the company did not provide its research purportedly showing it wasn’t responsible.

According to the court, further investigation was needed to confirm the cause of the spill.

Environmental Concerns

For Sleur, the case raised questions about Staatsolie’s commitment to protecting the environment, and he suggested that the secrecy surrounding oil contracts could also have related environmental implications.

“I have a very strong suspicion that contracts which Staatsolie has concluded with companies such as [TotalEnergies and Apache] also have clauses whereby Suriname will be held responsible for oil disasters and that the oil companies can walk freely in the event of a disaster,” he said, adding, “Suriname does not have the capacity for that.”

Staatsolie and TotalEnergies, however, both denied these suggestions.

“Please refer to the model PSC contract that states that in case of pollution and environmental damage, it is the responsibility of the contractor to clean and remediate,” Staatsolie stated. “It is only when the contractor is not replying in due time to the damage that Staatsolie can decide to manage it, on behalf of contractor and at contractor’s cost.”

This description of the model contract is accurate, but Staatsolie didn’t respond when asked if the clause is identical to the one included in the TotalEnergies/Apache contract.

As for Sleur, such assurances are not enough.

“Staatsolie can polish up the contracts as much as it prefers, but in the end it’s the multinational who decides what does and does not go in,” he said.

And even a strong contract, he added, is no guarantee that environmental laws will be enforced.

As an example, he pointed to Guyana, where a May court ruling accused the country’s Environmental Protection Agency of allowing an Exxon Mobil affiliate to operate without the required oil-spill insurance.

As a result of the “submissive” agency’s actions, Guyana and its people were put “in grave potential danger of calamitous disaster,” according to the ruling, which came in a case brought by Collins and another Guyanese activist.

The Guyana EPA and Exxon are appealing the decision and seeking to stay a court-mandated June 10 deadline for Exxon to provide Guyanese authorities with a liability agreement from an insurance company — or see its environmental permit suspended.

Bidding Process

Even if the Suriname’s oil contracts are made public, Collins said the process for choosing the companies that receive them should also be more transparent.

Though Staatsolie publicly announces bid rounds, much of the rest of the tender process is conducted in secret. The public, for instance, learns little about the identity of the bidders, the details of their bids, or related information.

Though this format is still standard in many countries, Mr. Collins said the trend is toward more transparency.

“I was looking at the Mexican [oil bidding] rounds and the Brazilian rounds,” he said. “Everything is there in the public domain. And you can see it proceeding: how the rounds up are going and who is bidding.”

Without similarly transparent bidding in Suriname, he added, the public may never learn what the competition may have been willing to pay for the country’s resources.

“If you have people who are benefiting outside of their fair share, they are robbing the rest of the country; they’re robbing the rest of us,” he said.

A lack of transparency, he added, can also open the door to potential corruption in the bidding process.

“I think that if your government is serious about auctions, it would approach countries where the results show clearly that anyone can win the bid and which have demonstrated that they have sturdy enough procedures to prevent collusion and corruption and, in general, any bid-rigging strategies,” he wrote in an email to CIJN.

Staatsolie and TotalEnergies, however, insisted that the country’s bidding process is already up to international standards.

“Bid rounds are always organised by Staatsolie in an international public and transparent way as launched and announced on the Staatsolie website and promoted at international conferences,” Staatsolie wrote to CIJN, adding, “Of course we are supporting transparency and we are making sure that in this process the investments and global commercial interest of our PSC partners in the joint ventures and Staatsolie are ensured and that future investments for Suriname are maximized.”

Freedom of Information Act

Meanwhile, journalists and other members of the public have limited recourse for forcing the government to turn over information about the industry.

Suriname has no freedom of information act (FOIA) despite more than a decade of promises from leaders.

Currently, a draft FOI act is before a parliamentary committee responsible for preparing it for consideration by the parliament. But Leeuwin — who recently helped provide input on the draft on behalf of the Association of Surinamese Journalists — said he is sceptical about the government’s commitment to the effort, which he believes that President Santokhi’s administration launched in response to pressure from the local media and international community.

Even if the draft law passes, it may not make much difference.

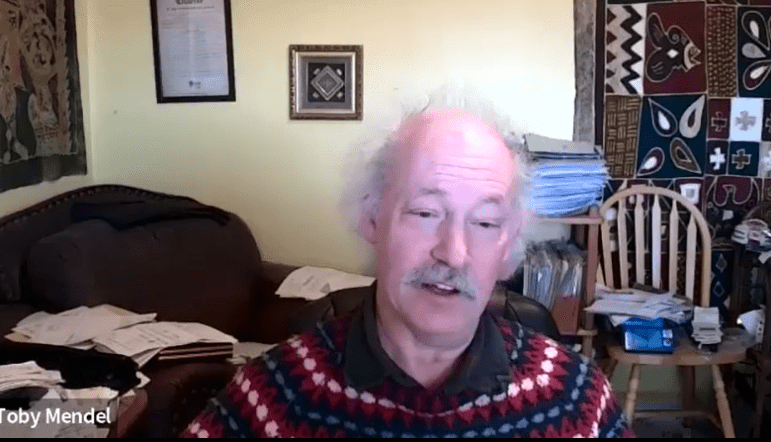

Toby Mendel, an FOI expert who reviewed the draft for CIJN, said it would be among the weakest such laws in the world. Mr. Mendel is the executive director of the Canadian Centre for Law and Democracy, which uses a detailed rating system to compare right-to-information laws for all countries that have them in place.

“As soon as Suriname adopt the law, we will put it on the rating and they will go at the bottom,” he said.

The Suriname draft, he said, is almost an exact replica of The Netherlands’ previous FOIA, whichwas replaced in May 2022. Until then, the Netherlands held the 75th spot on the RTI ranking, just between the United States and Israel.

Bright Future

Despite the delays, the Surinamese government is moving full-steam ahead to prepare for the expected oil boom. Last November, for instance, President Santokhi green-lighted a $5.4 billion new deep-water port to service the sector in the coastal district of Nickerie.

“This project should be seen against the background of the larger sub-regional development, and connects Suriname with Guyana, Brazil and the region,” he said at the time.

Jagesar, too, painted a picture of a bright future for offshore oil in Suriname, and he said money earned from the sector has potential to bring economic progress and sustainable development to the country.

“It will, unless it isn’t managed well,” he said.

But he acknowledged that Suriname’s record in this regard is not strong. During the past 40 years, he said, Staatsolie’s onshore activities have contributed some $4 billion to the state treasury without commensurate visible progress.

So he concluded that it will be totally up to the people of Suriname if the $15 billion revenue that he said the government could earn from offshore oil revenue in the next 20 years will be used for sustainable development.

Jagesar also acknowledged that the exploration process in Suriname appears slow in comparison to Guyana’s recent success, but he maintained that it has been relatively fast compared to similar efforts by other countries in the region and further abroad.

And even though a 2023 decision from TotalEnergies and Apache is not guaranteed, other companies have also reported early success with exploratory drilling. Meanwhile, the Demerara Bidding Round to attract more companies to invest was expected to be closed at the end of May, and Jagesar said 18 companies had shown interest.

However, the people of Suriname will have to take his word for it: He didn’t name the companies, and Staatsolie didn’t respond to CIJN’s request for a list.

This story has been edited to correct the spelling of Annand Jagesar.

This is an investigation completed by Harvey Panka for Caribbean Investigative Journalism Network with the support of the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) as part of the Investigative Journalism Initiative in the Americas.