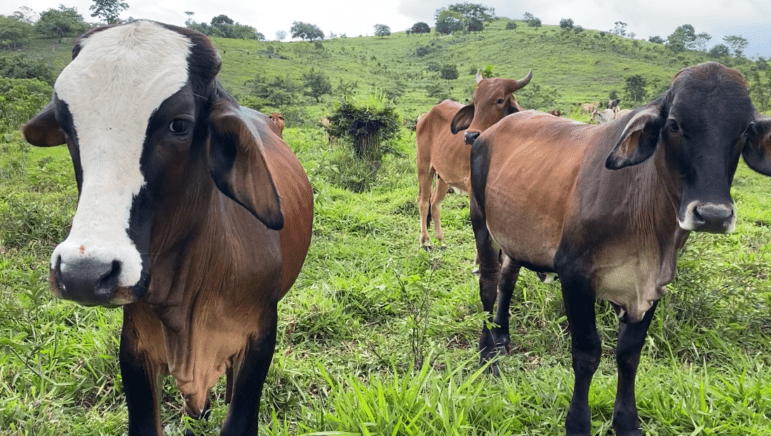

The Guatemalan cattle were back.

Dozens of them grazed in the clearing around Valentin Camp, a Belize Defence Force observation post located deep in the protected Chiquibul Forest near Belize’s disputed western border with Guatemala.

The presence of the cattle meant that the Guatemalan villagers who raise them were not far away.

Rafael Manzanero, who was leading a day-long visit to the area, was not pleased.

As executive director of the non-profit organisation Friends for Conservation and Development, his work includes managing a small team that monitors and protects much of the 176,000-hectare forest in Belize.

“We basically have noted and outlined cattle ranching as being the primary challenge that we face in the Chiquibul today,” Manzanero told the Caribbean Investigative Journalism Network. “That has been one ongoing for the last six years or so, in terms of the increase of that activity occurring along that western front.”

Incursions from Guatemala are not a new threat to the forest. But historically, they were carried out mainly by villagers engaged in subsistence farming, small-scale logging, or gathering the xate fronds that are prized by florists abroad. Those activities alone have led to the deforestation of thousands of hectares, some of which have partially grown back in many areas.

But today, Belize officials worry that the cattle ranching is on another scale altogether. Guatemalans who live in nearby villages raise the livestock, and they frequently cross the border and clear land for new pastures and watering holes in areas far from any Belizean towns.

But those villagers don’t typically finance the operations, according to Lieutenant Colonel Ricardo Leal, Chief of Staff for the Belize Defence Force.

“We are unsure who owns the cattle, but all that we know is that it’s being influenced by people that have lots of money, and also people that have direct connections with higher people in government [in Guatemala],” Leal told CIJN, adding that the ranching could be connected to narco-illicit activity. “I would like to stress also that whenever they’re doing these clearings, it could either be possible that they are doing it for illegal cattle ranching or they use it for clandestine airstrips.”

The suspicion makes sense. Over the past two decades, researchers monitoring Central America have increasingly blamed so-called “narco cattle ranching” for widespread deforestation in some of the most ecologically sensitive rainforests in the region.

Cartels, they say, have been taking advantage of lax regulations in the international cattle industry to use ranching as a front to launder money, smuggle drugs and claim territory.

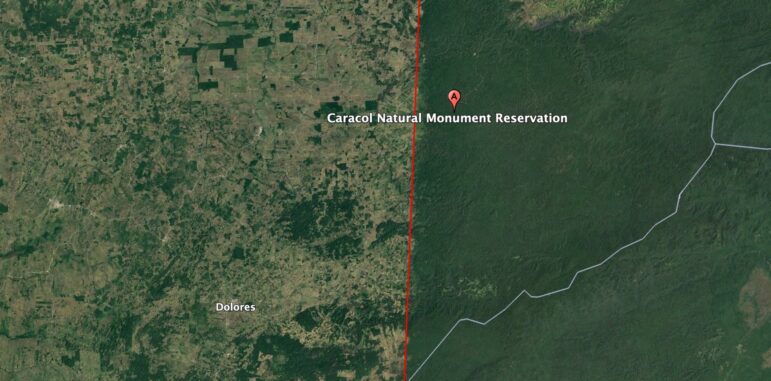

In Guatemala, the practice is believed to have been a leading contributor to deforestation in areas including the 2.1 million-hectare Maya Biosphere Reserve, which borders part of Belize’s Chiquibul Forest. But with the land on Guatemala’s side of the border increasingly becoming barren, Belize officials suspect that the drug cartels may be shifting their focus to Belize with the help of the Guatemalan villagers.

“The cattle have been moving more and more, and if you notice there’s a track already. So the cattle are just following that, so they would tend to appear there,” Manzanero said. “Many times they are chased, but they would actually of course come back again.”

Into the Woods

Belize takes its forests seriously. More than a quarter of the country is protected, and the Chiquibul is part of more than half a million hectares that make up the largest intact block of tropical forest north of the Amazon River.

The area is home to endangered species including the jaguar, scarlet macaw and tapir. It also forms part of an important ecological corridor in the region, linking to protected areas in Guatemala which in turn link to protected areas in Mexico to the north.

But because the Chiquibul is undeveloped, it is also difficult to protect. An August trip into the forest highlighted the challenges Belize officials face in patrolling a sprawling area with no roads and no permanent Belizean inhabitants.

Even reaching the Valentin Camp observation post was an arduous undertaking.

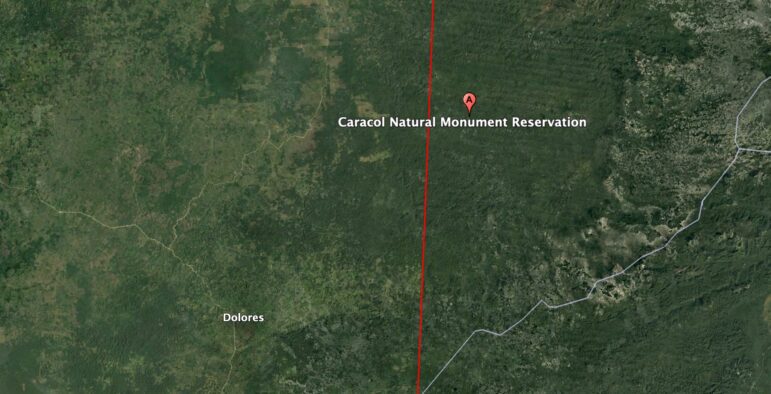

For this reporter, the journey began with a two-and-a-half-hour car trip from Belize City to Tapir Camp, a modest outpost for park rangers. Then came a thirty-minute drive in a four-wheel-drive jeep over bumpy jungle roads to the ancient Maya City of Caracol.

From there, the journey continued on foot.

Before setting off, Derrick Chan, the park manager of Chiquibul National Park, delivered a briefing in the clearing beside the Mayan ruins. He focused on basic safety for the hikers, who included this reporter as well as representatives from the Belize forestry department and non-governmental organisations.

To avoid losing the trail, Chan advised the hikers to keep at least one person in sight in front of them and another in sight behind them at all times.

The forest could be a dangerous place to get lost. The Guatemala-Belize border has been disputed since Guatemala was part of the Spanish empire and present-day Belize was controlled by Britain.

For more than 150 years, Guatemala — a much larger country with a population of about 18 million — has periodically claimed parts of Belize, which has about 400,000 inhabitants and is the only Central American country where English is the official language.

At times, the tensions have boiled over into violence in the border area. In 2014, a Belizean tourism police officer was shot to death near the Caracol ruins in a suspected retaliation by illegal Guatemalan loggers.

About two years later, Guatemala deployed troops to the border after a Guatemalan teenager was found shot to death following a confrontation involving Belize park rangers investigating illegal land-clearing near a border town.

Since then, the tensions have eased, and the border dispute is currently before the International Court of Justice with both countries’ assent.

But officials nevertheless remain wary, and the group of about half a dozen people was escorted by armed park rangers.

Journey on Foot

Because of the rugged, hilly terrain, the five-kilometre hike from Caracol to the Valentin Camp took about four hours.

As the hikers neared Valentin Camp, which is one of a dozen Belize Defence Force observation posts near the Guatemalan border, they began to see cows and other evidence of ranching activity. The scent of manure was fresh in the air, and they passed dozens of man-made watering holes.

Once they arrived at the hilltop vantage point of Valentin Camp, they could see large plots of land that had been cleared for cattle ranching in the surrounding mountains.

The cattle — which Manzanero said had crossed the border from the nearby Guatemalan village of La Rejoya — were too numerous to count. But FCD officials estimate their numbers in the hundreds in the Valentin Camp area alone.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Manzanero explained that the Chiquibul stretches some 43 kilometers along the border with no clear demarcation. Dotted near that border are 11 Guatemalan communities with easy access to the forest and its resources.

Several are now involved in illegal cattle ranching, according to Manzanero, who claimed that the great majority of human activity in the Belize forest originates from Guatemala.

“We are no longer really looking at small-scale activities,” he said. “I mean, just there [near La Rejoya], you could have counted over 70 cattle or so. And that’s only one small area there. There are other areas. So it is loss of territory in a way. Because if you notice there, the cattle are coming in.”

Pushing Back

The FCD is on the front lines of fighting back. The non-governmental organisation grew out of an environmental action group established in 1989, and it collaborates with Belize Defence Force soldiers to help protect the border areas of the Chiquibul. This work includes monitoring forest damage, patrolling, destroying fences, and otherwise pushing back against Guatemalan incursions.

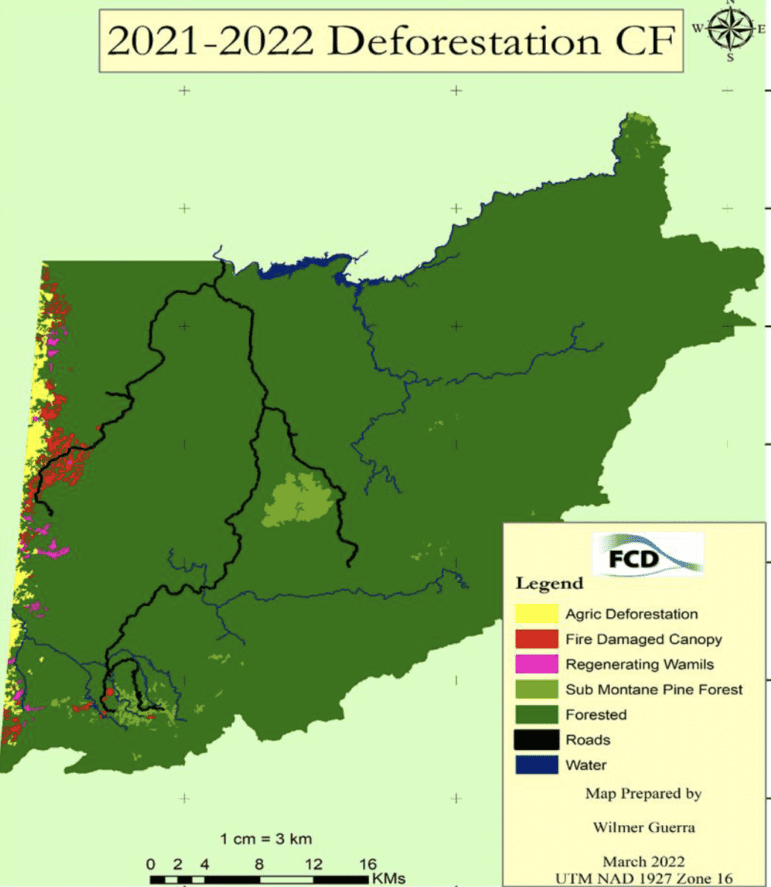

Such efforts have met with some success. A 2021 study found that deforestation dropped about 33 percent from 2018 to 2021 after increasing fairly steadily since 1989.

But the new ranching trend worries the forest managers. If it is not contained, they said, they foresee an increase in the average herd size and thus a dramatic increase in deforestation.

“What the people are seeing is that they don’t have any more land available for cattle activity in Guatemala,” Manzanero said. “That’s their problem; that is not our problem. If we’re not really strong in that messaging and in that action, then of course they will take advantage, which is what they are doing.”

The damage is already extensive. An FCD analysis of satellite imagery carried out last year revealed that approximately 1,920 hectares of land in the Chiquibul Forest had been cleared for agricultural purposes including cattle ranching and crop cultivation. These deforested patches — some of which extended more than two kilometres into Belize — averaged about 28 hectares, with the largest exceeding 350.

Currently, the cattle ranching is the “key question” facing the FCD, Manzanero said. The practice, he explained, is more organised than in the past, and the number of heads of cattle is huge.

“There have been a lot of discussions over more recent months on what we need to deal with in terms of that cattle that exists in that area and also in other parts in the Chiquibul,” he said.

But pushing them out is no easy task.

“Guatemalans come in: They would basically chase [the cattle] out, but then the following morning they are coming back in with their cattle,” Manzanero said. “So it’s use of the land. And it’s use of the territory.”

Meanwhile, the FCD’s resources are limited — the organisation employs about 50 people — and the BDF is also stretched thin.

“We have been saying that we need to be more adept,” Manzanero said. “We need to be much more robust in dealing with that problem. It’s remote. It’s rugged terrain. So the question is, how can we really take out that?”

One response strategy, Leal explained, involves extracting the cattle from the Chiquibul. But this is easier said than done.

“We don’t want to affect anybody’s livelihood, and at the same time we don’t want to affect our security in terms of we going there and, you know, we just remove [the cattle],” he said. “So it has some security aspects which we must look into before we make a move. But yes, there is a plan of action.”

Removing cattle from the remote Belize side of the border is also complicated by the needed quarantine process and basic transportation issues.

“There are some [narrow dirt paths] we call picados,” Leal said. “And we’re trying to see how we can probably extend those picados or at the same time build possibly roads. But, of course, it’s a sort of investment. And so that is some of the options that we have at the moment.”

Soldiers

The BDF is also working to deploy more soldiers to the area, according to Belize Border Defence and Security Minister Florencio Marin Jr.

That effort, however, comes with its own challenges.

“We just have to maintain active presence along the border with Guatemala, because as you know the population there is much more greater than ours,” Marin said, adding, “We also have different operations. Every now and again, we would go in and we would either try to retrieve the cattle or try to cut down the fence line, whatever, to discourage these types of activities.”

But such responses, he added, have been ongoing for years without eradicating the problem.

“At the end of the day, it is boots on the ground that will help keep the integrity of our border,” he said.

Meanwhile, the cattle ranching also brings a host of new problems for law enforcers and forest managers, Manzanero said.

“In the past, Guatemalans were coming in and they were harvesting the products from the Belizean territory,” he explained. “In this case, they are bringing their products in. So that creates a whole set of issues. For example, land: I mean, they are using land in Belize where they would put their cattle.”

The FCD also works with Guatemalan villagers. After stopping at Valentin Camp during the August trip, the group proceeded to a border area where FCD officials met with La Rejoya residents.

Their main goal was to advise the villagers on preventing wildfires, which in recent years have posed significant threats to the forest and public health. Often, Manzanero said, fires originate on the Guatemalan side of the border before spreading into the Chiquibul, where Belize officials struggle to control them because of the area’s inaccessibility.

The cattle problem was also discussed at the meeting, but Manzanero questioned the accuracy of some of the information his team received.

Though Belize officials suspect that the cattle owners are often wealthy people who don’t reside in the border towns, the villagers told a different story.

“What we heard from the community members, it seems that they are owning those cattle,” he said.

To prove otherwise, he added, is not easy.

“It’s really hard to see the linkages and to be able to make that connection,” he said.

Though officials still debate the best way forward, he added, one thing is certain: Action is urgent.

“The projections can tell us that if we don’t really deal with it, which we have been seeing also for quite some years, then it can become much more complicated for us,” he said.

Fly-Over

FCD officials also use aerial surveys to monitor the border area.

On a fly-over in August, they invited this reporter along to help demonstrate the scale of the deforestation caused by illegal land clearing.

The small aircraft, able to carry only three persons, took off from Spanish Lookout, a Mennonite community in the Cayo District. A few minutes in the air had the plane over Caracol and then near the border.

As it flew south from there, it passed over numerous cleared fields, dozens of manmade watering holes, and several herds of cattle. Some of them stretched several kilometres into Belizean territory.