Hovering over the postcard-worthy facade of indigenous communities across Guyana, looms a growing crisis triggered by changing climate conditions which threaten the traditions, health, and communal sustainability of the country’s first peoples.

Historically, the indigenous people have thrived on diets extracted from the availability of local flora and fauna. But changes in weather patterns and conditions have placed indigenous communities in peril as they confront challenges to food and nutrition security, and access to safe, potable water.

This dramatic change in daily living has forced changed attitudes toward traditional knowledge and practices. Today, the demands of alternatives confront them.

Limited access to safe water sources and changes in the location and supply of food supplies, particularly following extreme weather events, have led to nutritional challenges for these communities.

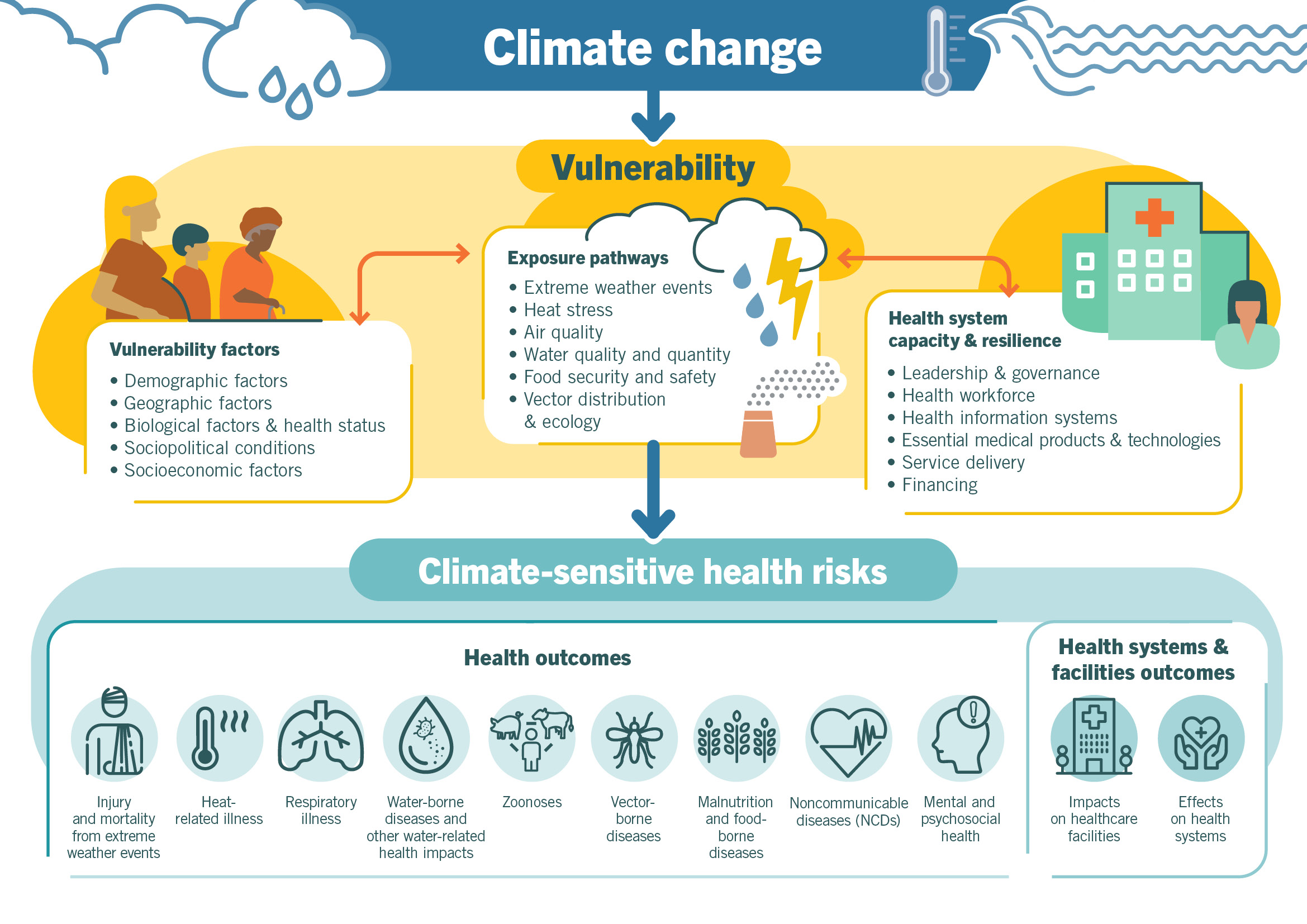

Guyana does not stand alone on this. On October 12, the World Health Organization (WHO) established an important link. Climate change, the WHO said, is directly contributing to global humanitarian emergencies from heatwaves, wildfires, floods, tropical storms and hurricanes and they are increasing in scale, frequency and intensity.

“Research shows that 3.6 billion people already live in areas highly susceptible to climate change. Between 2030 and 2050, climate change is expected to cause approximately 250,000 additional deaths per year, from undernutrition, malaria, diarrhoea and heat stress alone,” WHO says.

It was noted that the direct damage costs to health (excluding costs in health-determining sectors such as agriculture, water, and sanitation) are estimated to be between US$2–4 billion per year by 2030. In Guyana, the damage is yet to be fully assessed.

Across the mainland South American country, the impacts are felt both by those who reside along the coastal plain and in the hinterlands where indigenous communities predominate.

Once considered national “guardians of the environment,” the country’s first peoples now face the full brunt of climate impacts during the wet and dry periods.

Between August and October 2023, for instance, temperatures across Guyana remained between 30-34 degrees Celsius in the highs and 20-25 degrees Celsius in the lows, data from the Hydromet Office shows. The usual average at this time of year is in the vicinity of 23 and 33 degrees.

The situation led in September to a call by the Guyana Power and Light Inc (GPL) – which recorded a peak demand of 182 megawatts (MW) compared to 154 MW over the course of a single month – for consumers to “adopt conservation practices” as air condition use in urban areas grew.

In Guyana’s hinterland, the challenge extended to the availability of water for sanitation and the cultivation of land, and uncustomary heavy rainfall and dry periods.

Drought

In many communities across the hilly and riverine terrains of the country, a scarcity of cassava is for the first time in recent memory being experienced by villagers.

“My mom complained that since the sun got hotter, the cassava plants stopped growing and they remained at (one) height…” Immaculata Casimero, an indigenous rights activist and member of the South Rupununi District Council (SRDC) from Aishalton Region 9, explained.

But new dietary restrictions do not end there. In the deep South Rupununi, where Casimero resides, and in the neighbouring settlement of Sawariwau, she said cattle, the main source of protein for her people, has been dying due to limited water supplies and excessive heat.

She stressed at a recent district meeting with village leaders from twenty-one communities in the district there were bitter complaints about limited access to water.

“For the past three weeks, the pressure of the water (from public supplies) has been so low that it can’t even go into the tanks. Somedays we have to fill containers and keep water … or go to our neighbours for water,” she told CIJN.

In indigenous communities, it has been a norm for families to have their own water wells.

Casimero stressed that while her people have traditionally practised rainwater harvesting to complement their water supply from private wells, rainfall has been “just drizzles.”

Guyana is currently in an El Nino period resulting in a prolonged period of drought.

Meanwhile, in Region 1 which sits near the Guyana-Venezuela border, Marine biologist Felicia Collins explained that with the lack of freshwater outflows in coastal communities, there has been an intrusion of saline water from the sea.

“This is causing the freshwater fishes to migrate further inland and further up the rivers … Now they have to catch saltwater fish. This is not the preference of a lot of people …we have definitely seen the impacts,” she said. In this part of the country, fish is the main source of protein for the indigenous people.

According to Geographic System Information (GIS) Specialist and Forest Policy Officer, Micheal McGarrel, indigenous people face the brunt of impacts from changing environments due to their way of life; living off the land.

He said during the droughts there have been increasing wildfires in the savannahs. During the fires, he explained, in his village, Chenapau situated close to the Kaieteur National Park, Region 8, there would be an increase in mosquitoes.

McGarrel, who is also an indigenous rights activist, stressed while his people are very dependent on the lifecycles of the forest to plan, climate change has obstructed that cycle. This has resulted in food and nutrition security being adversely affected.

“We depend on the lifecycle of animals for our livelihood and what climate change has done, it has changed those life cycles,” he lamented.

“When climate was a lot more stable, we could have (told) when the season would change and make preparations to plant food and store foods but now that is not the case. We cannot predict the spawning season and we cannot plan.”

The current drought and intense hot days, Kato native, Kemol Robinson explained, have also resulted in children in his community falling ill. He noted the hot days and nights and dusty conditions of his Region 8, community have caused people to experience high fevers, vomiting and diarrhoea, along with the common cold.

Robinson told CIJN, that the drought has also caused their water supplies to diminish and streams from which they regularly source water becoming contaminated due to low water levels.

In the township of Madhia, in Region 8, the government was forced to intervene to meet the water needs of the people there.

A report from the Department of Public Information (DPI) stated that the Salbora Spring, one of the water sources in the township, has dried up altogether. This has resulted in businesses and homes requiring help finding access to potable water.

Salbora Spring provides water to approximately two-thirds of the region’s population. However, due to the weather, it is currently operating at around 40 per cent capacity, the report states.

In order for the government to alleviate the dire situation it has engaged in emergency procurement to have a well drilled to cushion the impacts the municipality faces.

Chief Executive Officer of Guyana Water Inc (GWI), Shaik Baksh in local media reported surface water levels have depleted significantly. He said as a result, hinterland communities are severely impacted.

To curb this challenge, his agency is gearing up to drill one hundred new wells in hinterland communities by 2025. Forty wells, the Stabroek News reports, are to be drilled this year with an additional 50 to 60 wells next year. This initiative reduces the community’s reliance on rivers, streams and creeks for potable water.

Too Much Water but No Water

The climate impacts, however, do not stop there, in the wet season where there is intensive rainfall, flooded riverine communities are cut off from potable sources of water and access to nutritional food that forms key elements of their diets.

In these indigenous communities, many of which are located miles away from the coastal capital of Georgetown, potable water has to be supplied during emergency response operations.

Both Collins and McGarrel explained cassava farmers face grave consequences arising from significant threats to food security in communities, in the aftermath of major floods.

Collins said to families in Region 1 where the Warraus, Caribs and Arawak nations reside: “Cassava is (now) considered gold” due to its scarcity. She explained the tuber is a main staple and is consumed heavily by families, many of whom have no alternative source of income to purchase other foods.

“When the farms are flooded and the cassava rots, some families have no other alternative for food,” she noted before pointing out that the situation can lead to malnutrition and health complications.

“Some days all me and my husband eat is bare rice. We can’t catch any fish. We have no vegetables. Everything rotten and die from this flood,” Gloria Miguel says in a report by the Stabroek News. Her comments were made in the aftermath of a historic flood in the Upper Pomeroon River in 2021.

“All the yams, eddoes, pears, golden apples, banana, plantains sapodilla, bora, everything — everything where I does get my lil change (income) from – gone! The flood come and carry away everything,” said Miguel, one of dozens of Upper Pomeroon flood victims.

WHO says climate change can seriously affect food availability, quality and diversity, exacerbating food and nutrition crises.

Steve Maximay, an EU-recognized expert on climate change explains that the phenomenon poses serious challenges to nutrition security in the Caribbean, given the vulnerable status of agriculture and the environment.

He notes that when crops and livestock, poultry and fisheries are affected during extreme weather episodes, human health needs are threatened with many not being able to access a balanced diet.

The 2021 floods which left a trail of devastation across the country also heightened the importance of accessing potable water during the climate crisis.

At times of flooding, rivers, creeks, and streams – on which indigenous people traditionally rely for relatively safe water supplies – become contaminated by forest droppings, mining activities, and unsanitary environmental practices.

Indigenous communities have for generations practised rainwater harvesting in order to assure continued water supplies during time of scarcity. However, it has become a challenge for some families who have limited containers to store water.

This has forced people in affected communities to depend on rivers and streams to execute their daily domestic chores such as laundry, washing of kitchen ware, and bathing.

“We have too much water but no water to use,” community service worker, Lennox Edwards from the Upper Pomeroon related.

“We have no other choice but to use the river water to bathe and wash wares. It is not healthy for us, but we have no other choice,” said Pauline Edmondson, one victim of 2021’s floods.

“If we want water to drink and cook, we have to keep the little rainwater we have because we don’t have these black tanks and the well from here is the same river water.” In some communities, water levels reach up to five metres in height.

After the flooding, it was reported that many children and some adults were affected by diarrhoea and vomiting.

Vector-Borne Diseases

As if the challenges to secure access to food and potable water in a climate crisis were not enough, affected households are forced to battle vector-borne diseases from mosquitoes.

Casimero told CIJN her efforts to keep a clean and sterile environment were apparently in vain as she has since contracted dengue and malaria, two common mosquito-borne diseases.

As she spoke with CIJN, she said “I thought with the dry weather the mosquitoes would have died but that is not the case. We have a lot of mosquitoes now and many persons in the community (Aishalton, Deep South Rupununi) are sick.”

She explained since contracting the virus, she has been subjected to bodily aches, colds, fevers, coughs nausea and muscle pains. Fortunately for her, she explained she was able to access medication and testing at her local hospital.

McGarrel noted that after the major 2017 flooding in his home village, health workers who were trained to conduct testing visited affected persons and administered tests and necessary medication to prevent an outbreak.

But while there is dependence on Western medicine to curb these illnesses, McGarrell and Robinson noted villages will also utilise traditional indigenous medicine.

Robinson noted in new cases of dengue at the start of the droughts this year, people heavily relied on traditional medicine. He, like McGarrel, explained that due to their villages’ remoteness, medications are not always readily available.

However, changing climate conditions have decimated some plants forcing villagers to go further into the jungle.

“In this regard, I have seen changes, especially in the area of traditional medicines you know like when the floods came it would have covered quite a bit of land, lots of plants would have died and pushed lots of people to go further to get their traditional medicines,” McGarrel said.

In cases such as Robinson’s journeys of up to two and three days are needed to find medicinal plants. The journey for these hinterland communities appears far more protracted and increasingly difficult as climate change continues to encroach on once pristine spaces.