When sailing on the inter-island ferry between Trinidad and Tobago, bending the northwestern peninsula of Trinidad, passengers feel the strength of the sea’s power. In that swathe of salt water and currents, where the Güiria and Western Peninsula almost kiss, seacraft, large and small, are tossed around Las Bocas del Dragón (Mouths of the Dragon – De Bocas in T&T English Creole).

It is a middle passage that was crossed skilfully, in the face of danger, by indigenous people. Spanish colonisers exited Venezuela through the Bocas del Serpiente, into the Bocas del Dragon, and into open waters, then to Trinidad and Margarita (Spanish Trinidad – Morales Padrón).

Members of Simón Bolívar’s revolutionary army executing attacks on the “realistas” from Trinidad’s islet Chacachacare (source). Trinidad historian Michael Anthony writes that Christopher Columbus was hesitant to sail through the Bocas on his third voyage to the “Índias”. For the last ten years, it has been crossed daily by Venezuelans seeking asylum, refuge, and better economic opportunities in Trinidad and Tobago.

The crossing and what it implies have not become any less treacherous. While Venezuelans flee difficult circumstances in their country, what they face in their hosting countries is not easy. The perceptions of their social make-up are varied. The negative perception of their presence in Trinidad and Tobago is often heard in the streets and seen on social media. “Venees” and “Spanish” are often the victims of verbal and physical attacks. That negative perception is not limited to the streets, IG, Facebook, and WhatsApp.

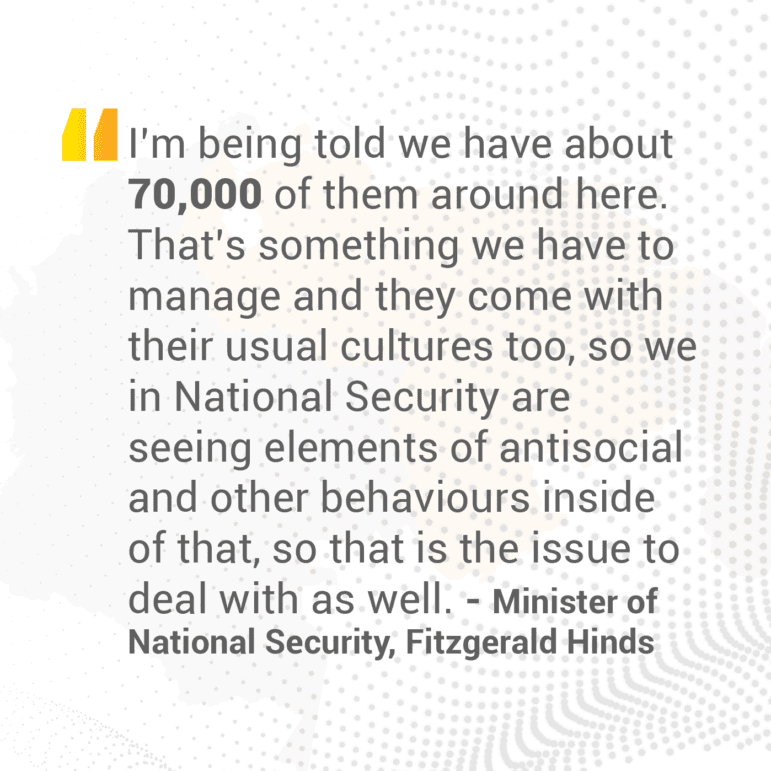

When, in May, Trinidad and Tobago Minister of National Security Fitzgerald Hinds announced the startlingly high figure of 70,000 compared to the official records, he sparked serious discussion and some controversy.

If there is a government minister who would know the most accurate estimates and understand the ever-evolving picture and numbers, it is the national security minister. In T&T, the Police Service, the Defence Force, and the Immigration Division all fall under the Ministry of National Security.

The unofficial numbers from high-ranking government officials tell an important story. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) notes that the March count totalled 6.09 million Venezuelan migrants and refugees living in nearby countries. The situation report notes that there has been a regularisation of migration status, but there are still countless Venezuelans who are undocumented. Therefore, they have difficulties accessing vital services.

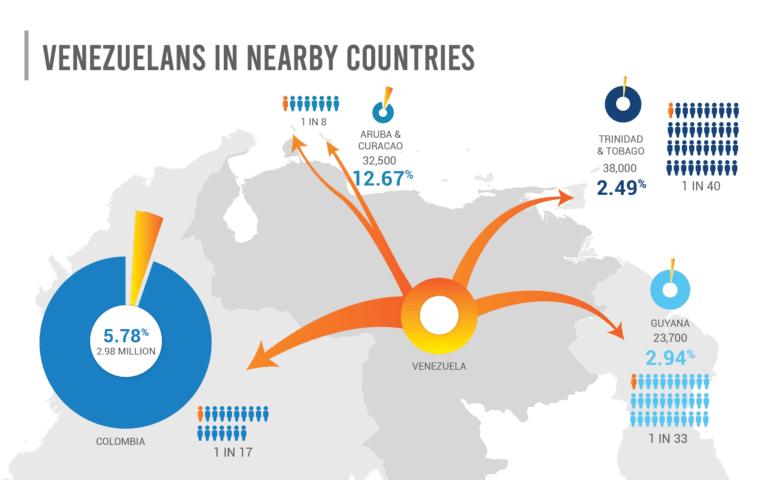

Whatever the number, there are tens of thousands of Venezuelan migrants living in Trinidad and Tobago. The countries that share land and marine borders with Venezuela have received vast numbers of migrants, refugees, and asylum-seekers for the better part of a decade. The Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela notes that there are 7.32 million refugees and migrants worldwide; 6.14 million have relocated to Latin America and the Caribbean (Feb. 2023).

| Trinidad and Tobago | Colombia | Guyana | Aruba & Curacao | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refugees and Asylum-Seekers | 38,000 | 2.98M | 23,700 | 32,500 |

| National Population | 1,526,000 | 51,520,000 | 804,567 | 256,441 |

| Percentage | 2.5% | 0.6% | 2.95% | 12% |

Most Venezuelan refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants in Trinidad and Tobago have lived with the daily tension and stress of the possibility of being held by police. They post WhatsApp statuses and groups of Latinos living in T&T, longing for a taste of their patria (under ideal circumstances) and some of their quotidian struggles, living in a foreign country, speaking a different language. They also post videos of confrontations with police, difficulty accessing standard services, and raids on nightclubs, restaurants, and bars. These videos often make it to social media and sometimes even traditional news media.

This year, on World Refugee Day, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Filippo Grandi, said,

Including refugees in the communities where they have found safety is the most effective way to help them restart their lives and contribute to the countries hosting them.

This means ensuring that refugees can apply for jobs, enroll in schools, and access housing and health care services. It also means fostering a sense of belonging and welcome that gives hope to refugees uprooted from their homes.”

As documentation, healthcare, and education are some of the basic rights and needs of human beings, and people seeking better lives, the numbers and accounts of Venezuelans in Trinidad and Tobago tell a story that is difficult and full of nuanced problems, not fully considered by any policy.

Administration and Registration

“When I went to renew the “carnet” (registration card), they put a stamp on it, but it’s all rubbed off now, and now, they are supposedly going to give out new cards.” Deivys Sambrano holds his “Minister’s Permit” from the Ministry of National Security of Trinidad and Tobago. It is significantly worn, having been in and out of his wallet since its issue in 2019 and long after its stated expiry in 2020.

Since arriving in Trinidad and Tobago at the end of 2017, he has worked several jobs – in construction, as an electrical apprentice, maintenance, cleaning, hospitality, and food. Like thousands of other Venezuelans in T&T, the difficulties of the humanitarian and economic crisis in his home country forced him to abandon his life there – studies in electrical engineering and physical education – to hustle in a new country. At that time, Venezuelan irregular refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants did not have legal permission to work in T&T.

In 2019, the government began registering Venezuelans in Trinidad and Tobago. Hoping to capture the names, fingerprints, photographs, and evidence of nationality of all – those who entered the country irregularly or not, documented or not. In total, 16,523 Venezuelans were registered and were legally allowed to work by the T&T government. At the time, there were doubts that the number of registrants painted a complete picture. Prime Minister Dr Keith Rowley said people and organisations with agendas “would have been better served by inflating the numbers.” Since 2019, there have been no instances of new registration.

Deivys says, “The process to get the card was difficult. It took me seven days of facing the cold, hunger, heat, and sun and waking up early for seven days to get the card. The process was a little long; there were problems with the computers, the internet, and the number of people.” Lines stretched for blocks while people waited to be registered. That was the only census of the Venezuelan population in the country and the only attempt to regularise them in any way.

Initially, those cards allowed registered refugees and migrants to work legally in T&T for one year. When the expiration date drew near, there was widespread fear among the community about what would happen. Since then, the cards have been renewed informally, without announcement of a continuation or change in policy by the government.

While Deivys says the card has not been of any use to him, as he has not worked in a formal business, it has been helpful to another migrant, Julieta (name changed), who chatted with me about her experiences. At 30 years old, like most Venezuelans in T&T, Julieta has had a wide range of work experience since arriving in her country of residence. She has cleaned houses, worked in a casino construction and now works in a food production business. “It wasn’t that easy to get the card. I got mine in 2019; we had to line up for three days.” Every six months, she has trekked to the immigration offices in Port-of-Spain, documents in a manila folder under her arm, seeking renewal.

“You have to make copies. Sometimes they give you a sticker, other times no… You lose the day of work, which you need because you are here to work, to dig out better food. You have to form a line, wait in the sun, and you lose the day of work, so it’s complicated.”

Julieta believes the registration card has allowed her better working opportunities and the peace of mind to work without worrying about the implications of employment without a work permit. It’s a problem that her husband still has.

Sitting at the dining table in their small studio apartment, her husband, Leonardo (name changed), explains that he is not registered with the government. He believes that he has been open to some unreasonable deadlines for complex tasks, harsh working conditions, and unfair dismissal because he isn’t registered and has not had a chance to do so since the initial process four years ago. Until these things are fixed, a Venezuelan can’t drive, a Venezuelan can’t start any type of business unless they have legal permission. On the one hand, I am thankful to Trinidad because I have been able to support my family.”

They all say that legitimate and official information is hard to come by. Many community “portavoces” – advocates/spokespeople share updates via WhatsApp, Facebook groups, and importantly, word of mouth. Julieta says: “They should translate the information and put it on social media.”

She explains that she knows many people from Venezuela who have left T&T to head back home or look for opportunities elsewhere and those who have come in after the registration process. “More people are coming, and now it is very difficult to get a job without the card. It is difficult for the people who are only registered with UNHCR.”

Her husband, Leonardo, is one of those people. He says, “until that is fixed, a Venezuelan can’t drive, can’t start any type of business, unless they have legal permission.”

Access to Health Services

In Trinidad and Tobago, public health care service for non-nationals is restricted to emergency treatment. The Ministry of Health formulated a policy in 2019 for non-nationals accessing their services. It says “based on the discretion of the home country, given its limited resources and capacity” that it can offer a limited range of services to all non-nationals. These are emergency medical services, primary healthcare services for maternal and child healthcare, and population and public health services, including immunisation and treating communicable and highly-infectious diseases.

While emergency health services are available, the community has reported barriers to accessing secondary health care – a cocktail of lengthy delays in triage, xenophobia, language and communication problems, apathy and lethargy, and uneven application of the policy are some of the reported issues.

Deivys says that in 2022, his niece had an emergency. She took headache pills with a high-caffeine energy drink, and they reacted badly. When he took her to the emergency room, “we were waiting for them to attend to her for approximately four hours and my niece fainted. I don’t know why they took so long to attend to her. And they didn’t attend to her in the way that I think they should have. They asked her if she was pregnant, checked her pressure, sugar and sent her home.”

He praised the care he and his wife got when she gave birth to their two children in Trinidad. “This year I had an emergency with my son; he is a Trini citizen. He was born here. He broke his arm. I can tell you this: The attention they give to children in the hospital in Mt. Hope is perfect care, but for adults, it is not the same. They fixed his arm and put on a cast. They gave me an appointment and, a month after, I had to go for a consultation for them to check up on his arm. I arrived and the woman immediately told me I can’t attend to you. I asked why and she said, because you are Venezuelan, and we don’t want problems. I had to insist, and I had to get his birth certificate to show them my son is Trinidadian and like all Trinis, he has rights.”

Leonardo complained about waiting six hours after he got seriously injured while working at a mechanical garage. “They took me to the hospital in St. James, and I had to wait for a very long time. They had a party in the hospital, and I had to wait until that was finished to get the stitches.”

Access to Education

Many Venezuelan families in T&T look forward to the start of the new academic year in September. Children will have the opportunity to start school for the first time.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, and international and national laws list education as a fundamental right. UN OCHA reports that Aruba, Curacao, Guyana, and the Dominican Republic have unrestricted access to basic schooling despite restrictive factors – the cost of school supplies, transport, uniforms, and cultural barriers.

Among the countries near Venezuela, for a long time, Colombia has, had a very open education policy when it comes to migrants. A UNICEF Education Case Study notes that the Colombian government has “an open-door policy”, as it has pathways to regularisation for migrants seeking services.

By June 2023, Venezuelan children from the migrant and refugee community made up 6% of the children enrolled in the Colombian school system, totalling 586,917 students. This total does not include the 61,959 Venezuelan children registered in state-run early childhood education facilities.

In Guyana, the education system run by the state is open to all. The education ministry reported that there were 2,036 children of refugees and migrants in schools across Guyana, 90% of Venezuelan parents.

R4V platform notes, however, that the students face difficulties being fully integrated into the system as language barriers and teachers are not trained to facilitate learning to second-language learners. Children in the system are widely reported to face marginalisation, exclusion, and bullying. There are also infrastructural and cultural hindrances to learning, especially in Guyana’s vast rural areas.

In Trinidad and Tobago, education for refugee and migrant children has long been a complex subject. Activists and community spokespeople have long been advocating for inclusivity. In July 2023, Minister of Foreign and Caricom Affairs Dr Amery Browne announced that the government was planning to integrate Venezuelan children into the primary school system at the beginning of the academic year in September. In Trinidad and Tobago, the average maximum age for primary schoolers is 12 years.

The Minister’s Permit – essentially allowing migrants to work did not give clearance for children to attend school. Non-national children in T&T need special permits to attend classes. Where their legal status does not permit them to attend school, T&T citizens, born to Venezuelan parents, also face language barriers to their ability to attend and benefit from classes.

R4V notes that religious school boards agreed to allow children in the community to enrol in their primary schools but reports that with support, “the Roman Catholic Schools were the only ones that moved ahead to accept Venezuelan children in their schools. Partners provided furniture, equipment, supplies, and training 131 teachers (120 females and 11 males) in teaching English as a Second Language (also known as ESL), a curriculum for transferable skills, and training on the identification of learning disabilities.”

Parents of children accessing education in T&T say unreliable internet connections, financial constraints, and the difficulty of juggling limited resources hinder their children from reaping all available education benefits. As the international community, community activists, and T&T social commentators have said publicly, the lack of access to education for approximately 5,000 children across primary and secondary school has caused other issues. Children of the refugee and migrant community are exposed to abuse, human trafficking, forced labour, unregulated educational facilities, and other perils.

The Living Water Community (LWC), a Catholic organization, has partnered with UNHCR, UNICEF, and the Trinidad and Tobago Venezuela Solidarity Network (TTVSOLNET) to offer education services to refugee and migrant children through their project “Equal Place”.

Started in 2019, classes are mainly online, with in-person support and extra-curricular activities. In-person classes are also organized in various communities’ centres with wireless internet access. This collaboration between the UN and LWC is not the only effort to have Venezuelan/Trini-Venezuelan children in schools. In 2019, PM Rowley said Catholic schools were allowed to register Venezuelan children, and the parents of over 2,000 children presented their children for registration; however, due to lack of documentation, specifically student permits, refugee and migrant children were not allowed to register.

The Minister of Education Dr Nyan Gadsby-Dolly has announced that this September-December school term, 100 students of Venezuelan parents are ready to be integrated into the school system. It remains to be seen how they cope in the first term of public schooling in T&T and how many more enter the system in the coming terms. In the meantime, approximately 5,000 students are eligible for placement, and their families wait to be enrolled.

With a tremor in her voice and water threatening to breach her eyelids, Julieta explains that she misses her daughter, who lives in Venezuela with her father’s family. She does not want to bring her to Trinidad, where she will not benefit from education. “My daughter is 11 years old. She is about to turn 12, she can’t study here… if it were possible, I’d bring her – I can’t bring her through the airport. I entered illegally, and it is difficult to bring her by boat. I wouldn’t bring her like that; I’m scared to bring her by boat illegally.”