The case of Hurricane Irma’s impact on Barbuda provides a significant example of what is often termed “disaster capitalism.” It is defined as the exploitation of natural disasters by governments and corporations to push through policies or projects that would otherwise face resistance, typically for economic or political gain. Residents of the island of Barbuda say that is what is happening to them.

Irma, a catastrophic category 5 hurricane caused more than USD$220 million damage to homes and infrastructure on the island of Barbuda. It also left a path of extreme environmental destruction on the island. The storm ripped the roofs off many homes and buildings, power poles were toppled and debris was scattered across the landscape. The police station was largely destroyed, medical services halted. Official estimates indicated 95% of structures on the island were damaged or destroyed.

What surrounded the approximately 1,500 inhabitants as they abandoned their tiny island on September 6, 2017 was utter destruction. What they couldn’t see was that their central government on Antigua was accelerating plans to sell or lease their lands, build luxury properties, and construct an international airport. The storm and evacuation became a catalyst for the government to roll back more than 300 years of land rights for indigenous Barbudans.

Barbuda, the sister island of Antigua, has a unique history of collective land ownership. Since the end of slavery, land in Barbuda has been held communally by all Barbudans. In 2007, the now opposition United Progressive Party (UPP) wanted to make it lawful so they passed the Barbuda Land Act.

However, in 2018, the Gaston Browne administration repealed the Barbuda Land Act. Attorney General Steadroy Benjamin argued that the act was unconstitutional because it prevented Antiguans from owning land.

The central government of Antigua and Barbuda pushed through new laws that enabled construction of a multi-million-dollar luxury tourism resort and a golf course known as the Barbuda Ocean Club on a protected wetland. The government also built a private jet airstrip through 300 acres of untouched forest. Both projects are funded and developed by the Peace, Love and Happiness (PLH) project, a billion dollar partner in the development of Barbuda.

Barbudans evacuated from the island and went 40 kilometers by sea to Antigua where the government said they would remain safe while the hurricane damage was surveyed. But at the same time, Trevor Walker, Member of Parliament for Barbuda remembers that the government was pushing forward plans of its own for a new airport that would facilitate international tourism.

CIJN’s investigation was not able to determine exactly how much the government has spent on the new airport but we learned that the administration was expected to fund a percentage of the airport costs while securing a fixed based operator (FBO) with PLH.

Lionel Hurst, Chief of Staff in the Prime Minister’s Office told CIJN that the government did not use treasury funds for the new airport but instead waived as much as USD $18 million in tax payments from developers to finance the construction. Detailed financial records and transparent accounts of these transactions remain undisclosed, raising questions about how much was spent and what was the source of funds.

When questioned about the cost the government bore for the construction of the new airport, the Chief Staff in the Prime Minister’s Office explained that PLH advanced tax payments of USD$14 million to build the runway and another USD$3 or USD$4 million to build the terminal and other facilities.

“However, monies that would be paid in the future were pre-paid and used to the benefit of all,” he added but did not respond to a request to clarify further.

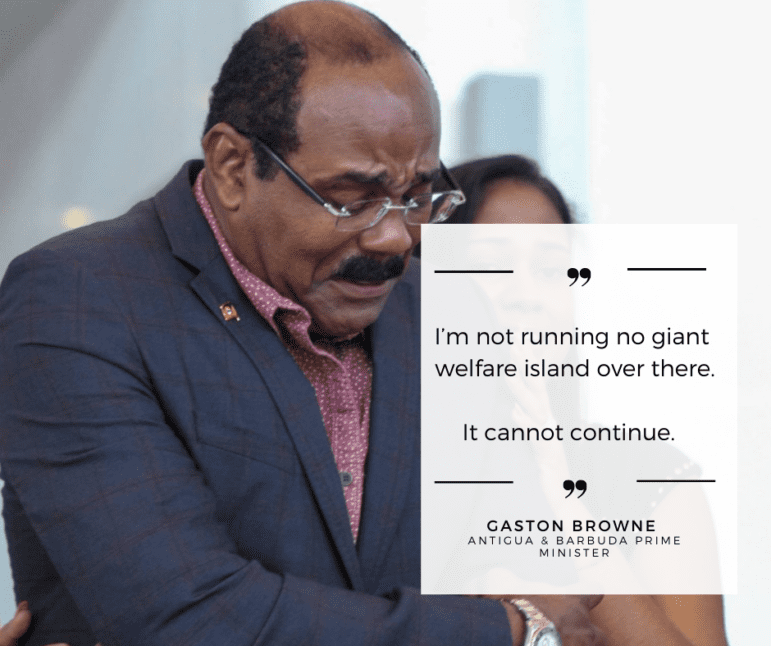

The Gaston-Browne-led Labour party government had been mulling for years over how to develop Barbuda and to collect more taxes and revenue from the sister island. Browne had repeatedly said that Barbuda’s contribution to the twin island state was miniscule. So naturally, he focused his energy on developing a tourism model for the island that would rival that of other small island states.

On an HBO special with Vice News days after hundreds of people were displaced, he repeated his often-stated vow he would no longer allow Barbuda to operate as a “giant welfare island”.

MP Walker believes that the prime minister’s personal opinion of Barbudans has and continues to influence not only the divide with the sister isle but is the reason for the poor communication and distribution of relief items.

“We know how prime minister Gaston Browne is. He takes a lot of things very personal,” Walker remarked.

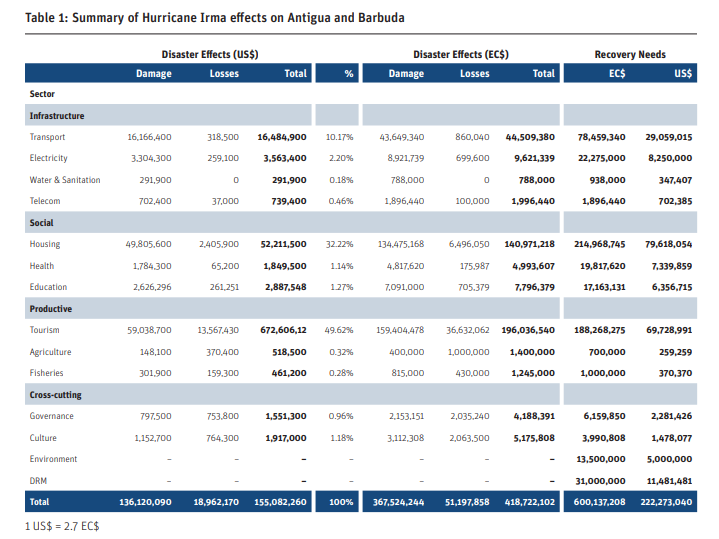

In 2017, by request of the government, and with support of the ACP-EU NDRR Program working jointly with the United Nations, European Union, Caribbean Development Bank, and the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank, a report showed that recovery needs for Barbuda amounted to US$222.2 million. US$ 79.6 million of the amount was needed to repair or replace houses, since 45 percent of the houses were left uninhabitable and 28 percent required complete replacement.

Damage and losses in the tourism sector amounted to USD $72.6M (XCD $196M) – the largest loss of Irma. But, with its entire infrastructure in ruins, Barbuda was in need of almost everything.

In response, the government began accepting pledges and soliciting funds towards recovery efforts on the island.

International government agencies, donors, and private citizens in the first two months after the disaster pledged more than USD $12 million while a fundraising campaign for the Caribbean promised to forgive $1 billion in debt and contribute a total of USD $1.3 billion to Caribbean countries affected by Irma.

But Walker who is also an ex-officio member of the Barbuda Council is unconvinced that much of the money received by the government was actually spent on recovery efforts. He told CIJN the Council, which serves as the island’s local government, wasn’t informed how any money was being spent.

Walker insists there has been no communication or transparency from the central government on post-Irma development. He said the Barbuda Council hasn’t been informed how much money and materials were collected or how that was distributed.

Instead of seeing Irma’s destruction as an opportunity to build back more sustainably and improve the island’s resilience to storms and climate change, the government continued to focus its energy on developing and expanding Barbuda’s tourism industry. Key infrastructure, such as disaster response systems, road works, health, and sanitation facilities, remain underdeveloped or in disrepair.

Apart from initiatives by outside donors, our investigation did not find that the government invested much of its own resources into building a “green Barbuda” as the Prime Minister promised.

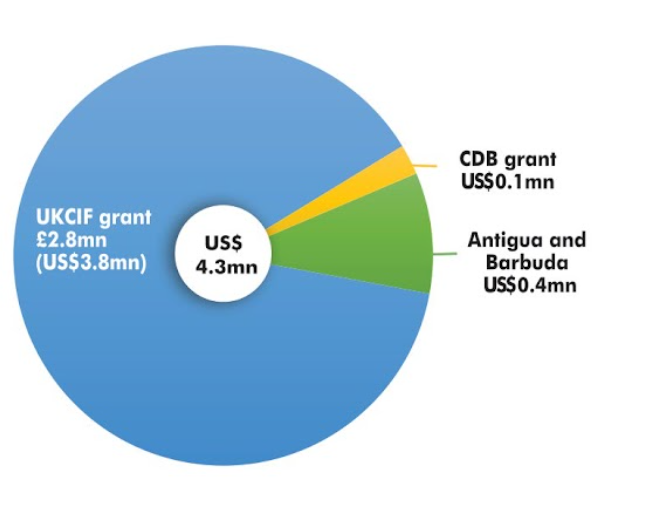

For example, international donors funded most of a hybrid electricity program that buried electrical cables underground. Barbuda now has a more resilient system made possible through a grant from the United Kingdom Government under the UK Caribbean Infrastructure Fund (UKCIF).

According to the government requested needs assessment, improvements to the national disaster risk information framework and emergency communications network should have been done alongside the local government (Barbuda Council) on Barbuda.

Gulliver Johnson, an executive member of the Barbuda Land Rights & Resources Committee (BLRRC) highlighted several missing components needed for Barbudans to prepare for another hurricane.

He said basic emergency needs like satellite telephones, a warning network and a comprehensive plan for residents before, during and after major events were still missing. He stressed that it’s highly unlikely any Barbudans will choose to evacuate considering the catastrophe that happened after hurricane Irma.

In 2024, Barbuda still bears the scars of Hurricane Irma. Damaged homes and churches remain unrepaired, roads are rugged, and a temporary dumpsite near the airport continues to be filled with industrial waste and cleanup debris.

“The hurricane efforts … provided to Barbuda after the storm for me was a drop in the bucket.”

Jacklyn Beazer-Desouza

They’re shells, they’re not homes

MP Walker

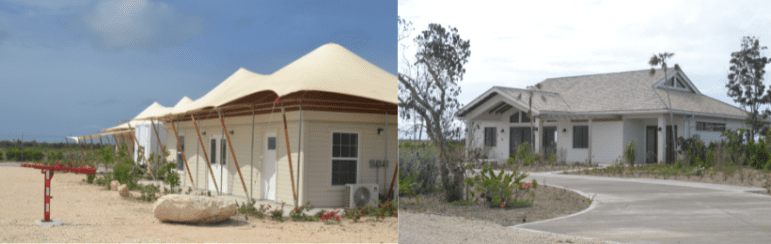

Member of Parliament Trevor Walker said he was unimpressed by the outcome of a USD $5.5 million (XCD 15 million) grant which was donated by the European Union to build homes on Barbuda.

A total of 91 homes were built under the guidance of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The original target was 150 homes, however our investigation found that the number decreased due to costs of material transportation and local contractors that weren’t factored into original estimates.

We reached out to the local UNDP representative for an explanation. At first, the answer was that authorization was needed for any reply. Subsequent enquiries went unanswered altogether.

What is visible upon entry into Codrington, the only major village on Barbuda, are small unpainted concrete structures that locals call “hurricane homes.” To them, these represent some of only a few tangible efforts to help Barbudans. They complain that the structures fall far short of what would be a “liveable home.”

Contractor Joseph Beazer said he is also disappointed by the size and state of the homes.

The 72-year-old says he and a few other contractors on Barbuda, have yet to receive thousands of dollars owed to them by the government for roofing or other repairs completed on several homes on the island.

He told CIJN he is still awaiting payment for two homes he repaired valued at more than USD $20,000. Another contractor, Romeo Desouza, says he’s still owed almost USD $80,000 for repairs he was hired to do by the National Office of Disaster Services (NODS).

As a contractor familiar with Barbuda’s storm damage, Beazer expressed doubts that the so-called “hurricane homes” could withstand another major storm.

Business woman Jacklyn Beazer Desouza shared similar sentiments. “I think the homes that were built, for the folks that got the homes as far as I could see, weren’t even done to 60%, 40% of what they should have done.”

Gulliver Johnson, executive member Barbuda Land Rights and Resources Committee said there was a general sense that Barbudans who could have best benefitted didn’t get the help they needed.

A Loss of Trust

Promises made by the government to disclose detailed bank statements and to ensure transparency have gone unfulfilled. Lionel Hurst, the Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff, during a Cabinet press briefing, had promised to make the source of funds public in October 2017, barely a month after the hurricane.

The right to access public information is entrenched in law in Antigua and Barbuda. But the government has failed to provide clear information on the use of relief funds and the absence of an appointed Information Commissioner.

Attempts by local officials and external donors to trace the allocation of funds have been met with resistance or silence. Devon Warner likened it to “pulling teeth”.

“It’s like pulling teeth to get information that is required, not only for us as Antiguans and Barbudans but these are information that is required by our international donors, our friends who assisted us”

Devon Warner

One of the donors, a UK philanthropist, has been vocal about funds vanishing from his charity. The Barbuda audit is expected to examine the US$1 million (XCD $2.7m) donation from the UK-based Steve Morgan Foundation, which is currently held by the Global Bank of Commerce (GBC).

The true status of the bank is unknown at this time. Antigua and Barbuda’s High Court ordered that information only be revealed in chambers behind closed doors to prevent certain information from being recorded by the media or the public.

Morgan maintains a home in Jumby Bay, Antigua and canceled an interview with CIJN to discuss his missing $1 million donation that was specifically aimed to help Barbuda.

However, in a previous interview streamed live on Facebook, he said he was instructed by “various members of the government” including then Financial Secretary Whitfield Harris to send the money to Global Bank of Commerce in 2017. It is where the government kept some of its earnings generated by the sale of passports and other public-private revenue.

Prime Minister Gaston Browne said in parliament earlier in 2024 that the government no longer banks there after word spread that the bank was in financial difficulty and that some depositors had been unable to withdraw their money.

“It [the money] sort of disappeared into a black hole. After a while we chased this up asking what happened because they had not been asked to sign as co-signatories,” Morgan said in an interview with Phoenix Free Press earlier this year.

The money was meant to go towards rebuilding houses destroyed by the hurricane. Morgan tried to liaise with the government over several years. A transcript of the correspondence between Morgan and the government was obtained for our investigation.

In September 2017, Konata Lee, the Secretary to the Cabinet, emailed Morgan. The message informed him that the government had taken steps to set up a special account to facilitate the receipt of contributions. Further, the government requested that measures be put in place to ensure that all Barbuda relief contributions would be handled with the highest degree of accountability

The last message sent by Morgan to the government was dated July 2023. In it, Morgan reiterated decisions made in a meeting three months prior. These included a decision by the Antigua Government to remove the $1m from the Global Bank of Commerce by way of a guarantee scheme and place the money into an interest-bearing ESCROW account, in a different bank pending a jointly agreed expenditure on a project in Barbuda to commence later that year.

Morgan outlined the following:

- The use of the funds for the construction of the Barbuda Justice Complex was inappropriate. Instead, the funds should be used towards a social housing project for the benefit of the people of Barbuda.

- There was a current legal process in securing the freehold of land identified for new housing in Barbuda and that process was expected to be completed within two months from 3rd April.

- Pending completion of the legal process above, a housing scheme would be procured using the US$1million grant plus a minimum of US$2m which had already been allocated for the same purpose from other sources.

Morgan’s follow-up attempts to reclaim the funds or redirect them to appropriate projects have apparently been met with silence from the government since a meeting in July 2023.

That one case of a disappointed aid donor has raised wider fears that Devon Warner and Trevor Walker feel will make it more difficult to access aid in the future for the people on both islands.

Clearly, an accounting or audit of relief funds and donations would resolve many concerns.

CIJN submitted Freedom of Information (FOI) requests to the Department of Treasury and to the Ministry of Finance for data on funds received and spent on behalf of Barbuda relief. Despite phone calls and follow ups, these government agencies have not responded.

Questions to Prime Minister Browne also went unanswered. Without even the most basic information there is no way to know the details of the aid offered and the relief provided. Meantime, after seven years, some of that infrastructure remains in ruins.

“I’m not comfortable that we are where we are supposed to be, unfortunately,” stated council chairman Devon Warner.

It was only at the start of this CIJN investigation that Director of the Audit Department, Dean Evanson began compiling and auditing the pledges received by the government. His actions are as a result of several letters issued by Warner.

Evanson said while the Finance Administration Act 2009 and the Office of Director of Audit Act 2014 does not outline a timeframe on how long he can take to complete the audit, he anticipates that the it may take three to six months.

Evanson told CIJN he is the one who chooses what to audit. The law that governs his line of work implies that he could audit everything or nothing at all. He didn’t explain why an audit of relief funds after hurricane Irma wasn’t a priority for the last seven years.

Chairman of the Barbuda Council Devon Warner has a theory. He thinks the central government is worried the audit could reveal embarrassing details about its role in delivering critical aid.

The audit, once complete, will include monies spent by the central government through agencies like the National Office of Disaster Services (NODS), financial data from the Ministry of Finance, as well as a list of all the donors during a fixed period after the hurricane.

Absent cooperation with the Central Government, Walker and Warner said the council had to resort to working directly with NGO’s and soliciting donations from individuals to rebuild public spaces like schools and provide general assistance to Barbudans.

There is a bitter and long standing rivalry between PM Browne and opposition political personalities on the island of Barbuda. Since hurricane Irma, those differences have become even more pronounced.

As early as July 2023, the prime minister touted his plans to make Barbuda a “Jumby Bay on steroids”. Jumby Bay is a 300-acre private, luxury island two miles off the coast of Antigua which is owned and leased by wealthy investors.

Speaking in Parliament, the PM ridiculed efforts to derail his development plans, telling lawmakers the issue of land ownership was already decided by a British High Court, the Privy Council. But lawyers for the Barbudans say the land issue remains unresolved in its entirety.

PM Brown contends they’re beating a dead horse:

CIJN’s investigation resulted in several important observations about the current situation:

As another hurricane season looms, the urgency for accountability and transparency in disaster relief efforts has never been more critical. Barbudans express hope that a comprehensive audit of past aid will ensure future donations are properly utilized to rebuild their island and restore trust in the system.

Barbuda has only one prized resource: the island’s pristine, undeveloped land. It is not surprising Barbudans view bargains being struck between the central government and wealthy investors as ignoring their heritage and interests.

Barbuda was a slave colony producing sugar cane beginning in the 1600’s. When Britain’s Parliament outlawed slavery in 1833, those who remained were given “communal rights” to continue farming the land. Today, their descendents view those rights to the land as nothing less than reparations for slavery.

Despite these challenges, Barbudans must come to terms with the need for modernization. It is essential to find common ground on land issues to develop the economy in a way that aligns with their identity. Both sides should reduce inflammatory rhetoric. What they need instead is to negotiate and collaborate for the future of Barbuda.

This story was supported via a Fellowship from Media Institute of the Caribbean (MIC) and Internews with funding provided by Clara Lionel Foundation (CLF).