Jutting out of the ocean as if a battle-weathered warrior is the island nation of Barbados, one of the many Small Island Developing States holding the frontline against the effects of climate change.

Despite Barbados’ position on the battlefield, they did not start this war and did not set the rules of engagement. Instead, Barbados has to wage a campaign at international climate conventions to open up funding sources and adjust universal goals to suit its own reality.

Nowhere is this more evident than in two paradigm-shifting projects: the new fishing regulations, which focus on measures to protect marine life, and the island-wide conversion to electrified vehicles by 2030. Though meeting climate objectives are high on the minds of Barbadians, experts are urging leaders to ensure that climate policies do not neglect the country’s unique circumstances.

“There are clear ways you could see that things aren’t tailored for our situation,” said Dr Shelly-Ann Cox, Ocean Professional Fisheries Management Specialist and CEO of Blue Shell Productions. ”And there are clear ways that you can see it could help, but then [we get] overwhelmed, there are no resources to build it out. So you need to figure out the best way to balance and still be able to use your resources within sustainable limits.”

Global Goals, National Realities

From the creation of the Kyoto Protocol until the recent climate change convention held in Glasgow, Scotland, world leaders, scientists, environmentalists, and non-governmental organisations have collectively promised to cap global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, pushed mainly by the Alliance of Small Island States.

In 2015, under the Paris Agreement, all signatory countries created a legally binding “global pact” to reduce emissions and greenhouse gases. Out of this, countries negotiated their Nationally Determined Contribution, monitored by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

Currently, government leaders in Barbados are announcing ambitious timelines for completing such goals while still attempting to source funds and get buy-in from citizens.

In 2021, Barbados submitted the “Barbados 2021 Update of the First Nationally Determined Contribution” This document outlines how Barbados will meet its obligations to the international community.

Adaptation and building resilience to climate change is Barbados’ main priority. Building resilience and adaptation capacity have now become fully integrated into the development of all government policies, in particular the 2021 Physical Development Plan update and Roofs to Reefs Programme. “

The Roots to Reefs Programme is one of the leading programmes designed to manage Barbados’ climate policies. The programme’s fundamental purpose is to direct how Barbados will manage to reach its national climate targets.

Ricardo Marshall, Director of the Roofs to Reefs Programme in the Prime Minister’s Office, details how the programme acts as a blueprint for Barbados’ international commitments.

“What we’re talking about is our development model for the next decades, and it represents our national initiative for sustainable and resilient development, to take an integrated whole country approach. “

The achievement of these measures, though, is harder to come by due to the climatic risks facing small island nations. Higher carbon emissions and other factors not created in the region make Barbados more susceptible to natural disasters and make it more challenging to bounce back when disasters strike. Mr Marshall gives an example.

“When [Hurricane] Maria hit Dominica, Dominica lost 226% of their GDP overnight. There’s one country in the region that gets hit every year, the United States of America. But even when they get hit, they lose less than 1% of GDP. When you’re like us, and you get hit, you can lose 226% of GDP overnight. So that’s the reality you’re facing.”

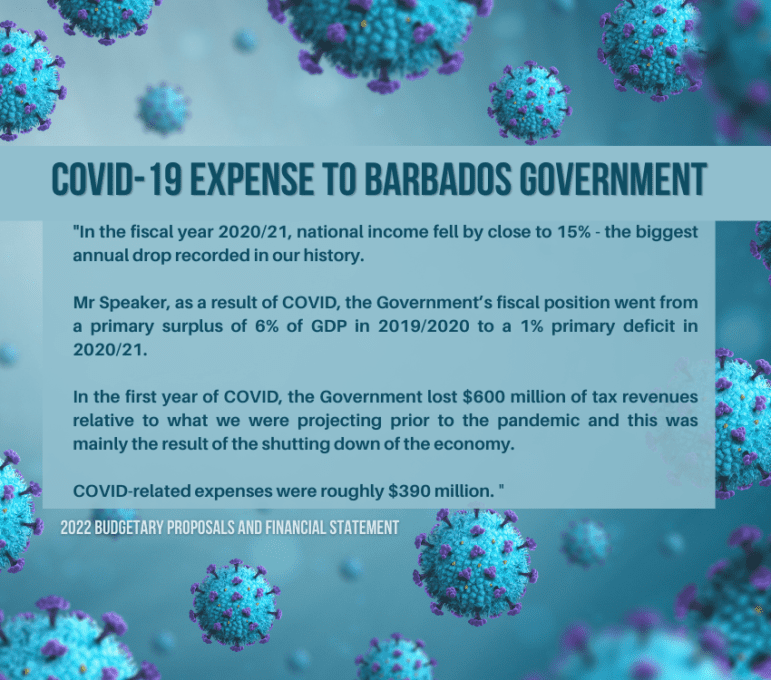

The COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have also diverted significant sums of funding from the national budget toward buffering the population against their effects.

“They [COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine] certainly make everything else harder, and we have less money available. If I was planning to improve the fish-landing site at Oistins, but I had to buy new vaccines for COVID at three times the price of the developed countries because I was small and people say not selling you unless you buy at X – those are the sorts of things we are making trade-offs against everything else.” Mr Marshall further demonstrates.

Underpinning everything is funding. Available funds make climate programmes possible.

The Prime Minister of Barbados, Mia Amor Mottley, travels internationally and champions the cause of “fiscal space” for SIDS countries to achieve their NDCs.

At the recent IX Summit of the Americas, Prime Minister Mottley highlighted this issue in her address to the open assembly and again later in talks with the Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Kristalina Georgieva.

“We simply do not have the fiscal space to respond to crises not spawned by ourselves, but spawned by others…

“…We need to reform the international financial institution’s architecture. How can we have an international bank for reconstruction and development that does not reconstruct and develop in today’s world? Where is the climate finance being targeted when the numbers show that only 15% of climate finance is going to the climate-vulnerable countries?”

Lending rules devised by developed nations and funding agencies base their access on a country’s Gross National Product (GDP) rather than its vulnerability.

“If you are a high likelihood over the next two to three years of losing 5% of your GDP or more in a climate-related event, you should be considered vulnerable, and you should get access to more grants as well as more loans and loans at better concessional terms,” stresses Marshall, the Roofs to Reefs Director.

Beyond changing funding metrics is the access to international lenders; not all offer the same terms. The World Bank, seen as the most attractive for low rates and higher lending amounts, is not fully available to Barbados because of the GDP barrier.

Despite these concerns, meeting the country’s climate goals can only happen by instituting changes negotiated at the international level into practical programmes.

Fishermen Struggle to Adapt

Fishing has a rich history in Barbados. Fishermen Patrick Jones, John Anthony Husbands and Kerry Coppin all started fishing in their youth.

“It’s been more than 50 years I’ve been fishing for sure. I started at ten years old. My father was a fisherman, and my mother was a fish vendor. My brother is a fisherman. My business is food network and fishing.”, John Anthony Husbands exclaims with pride, surrounded by other fishermen busy preparing a catch in the fish station at Half Moon Point in the country’s northernmost parish of St. Lucy.

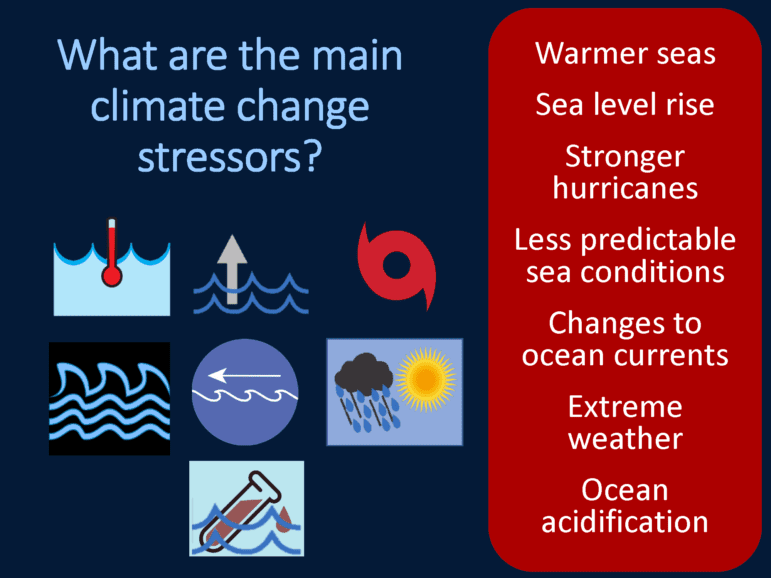

Regardless of the joy fishing brings, fishing is a difficult pursuit made even more challenging by climate change. Fisherman Patrick Jones explains why this is the case.

“Due to climate change, the flying fish are not migrating like before. The other day some guys were down Tobago; we had a lot of fellows calling us on the radio saying that the fish up in the southeast. [Usually], we would find these fish down in Tobago, but now it’s very hard to get.”

For long-line fisherman Kerry Coppin, the sargassum seaweed is causing havoc to fish stocks.

“The seaweed, it’s killing the flying fish, not much flying fish, the dolphin [Mahi Mahi not the porpoise] is really small. When a man leaves home, he’s got his family to feed, so whatever he sees he’s going to catch, the tarpin, the amberjacks they love the moss [seaweed] we catching them plentiful; otherwise, there’s nothing more. It’s not like the days gone by.”

The number of stressors to the fishing industry caused by climate change and regional commitments to international accords led to the creation of the Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism in 2003. The mechanism is a regional body overseeing the implementation of the Protocol on Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Management in Fisheries and Aquaculture under the Caribbean Community Common Fisheries Policy.

The fisheries policy looks at “the cooperation and collaboration of Caribbean people, fishermen and governments in conserving, managing and sustainably utilising fisheries and related ecosystems.”

In Barbados, the adaptation of the CCCFP into legislation is still in draft form as the Fisheries (Management) Regulations 2021. which will outline “a list of prohibited fishing methods” and gear, areas for fishing and species to fish.

“This boat we are carrying out now, we have to put about $3300 BDS in expense [each trip]. If we don’t get that money, you know, I get in trouble. The fishermen does get good money when you get a good catch, yes, but how often you might get a good catch?” Patrick says poignantly.

Veteran fisherman John Anthony Husbands believes that without financial support to the Fisherfolk when establishing new protocols; some fishermen could find that a career in fishing is no longer within reach.

“You gotta have to have money for the new protocols. This means that the poor man that has none will be sifted out or will go and work for the ones that got the money. It will not be a poor man’s business anymore. It will be a millionaire’s business.”

When it comes to funding, according to Ocean Professional Fisheries Management Specialist Dr Shelly-Ann Cox, there is not an overall budget to implement the new fisheries policy. Fisheries officials have to source for individual elements of the policy.

“In many cases, the contribution [fishing] to GDP is 1% or less. So there is no priority; it comes down to writing these projects to Global Environment Facility, the Green Climate Fund to try to build out interventions to support the overall objectives of the policy. The policy never really had an implementation plan or an indicative budget, so I don’t think none of that exists; if it did, it would be millions, probably trillions of dollars (BDS) for countries around the region to implement these things.”

The Transition to Electric Vehicles

Moving from the reefs to the roads of Barbados, international agreements are guiding Barbados’ transition to renewable transport by 2030.

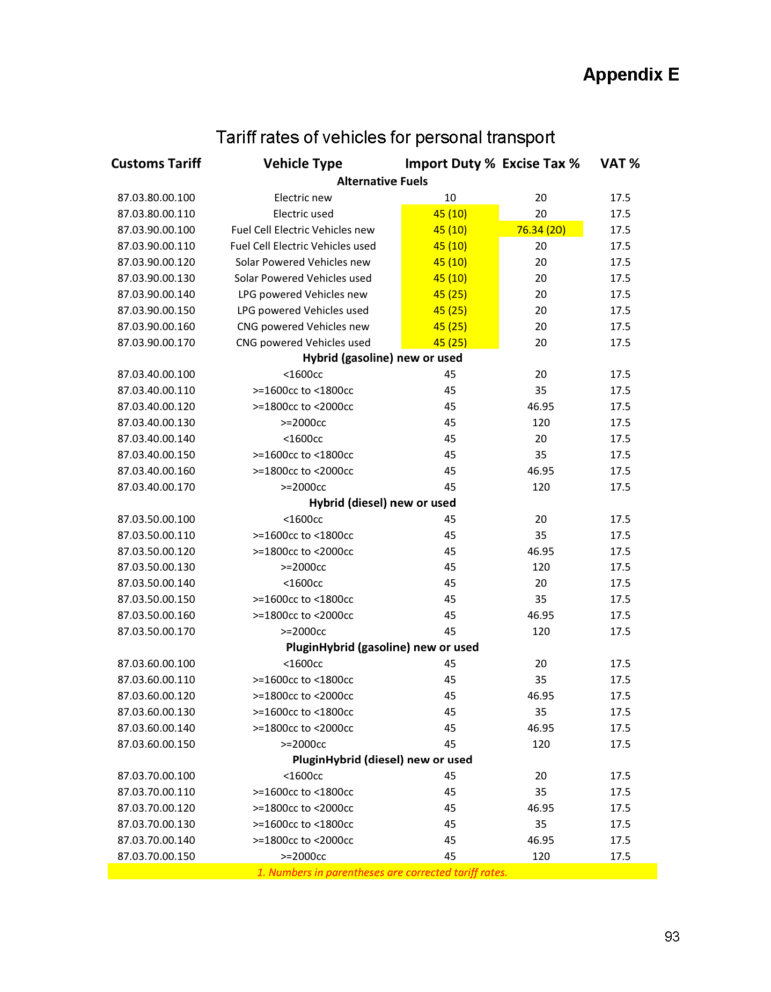

To reach this deadline, the current administration presented concessions in the 2022 Budgetary Proposals and Financial Statement (pg 46) for persons to purchase electric vehicles (see graph and appendix).

William Hinds, Chief Energy Conservation Officer in the Ministry of Energy and Business, described why Barbados signed the agreement although it is not legally binding.

“Our commitments are basically being masters of our own destiny and having our own resources. Using renewable energy not only helps us save the world but also helps us to create jobs and import less fossil fuel. And in doing that, we are actually using less of our precious foreign exchange.”

Nissan Leaf driver and JARP Distribution Owner Richard Perkins sees electric car ownership as a “no brainer” decision, especially in light of supply chain interruptions and COVID-19 lockdowns.

“When you consider the size of Barbados and the amount of sunshine we get per year, anything electric, particularly with the ubiquitous nature of solar panels, it is a no-brainer,” Perkins said.

His only challenge is the “garage’s ability to repair and sourcing parts” because “electric vehicles are still new to Barbados”.

Although Barbadians see the necessity to change, they have concerns over the eight-year conversion plan.

Robert and Delores Sandford, husband and wife taxi owners, have questions on the structure of the transition.

“If going green is not the same or parallel to our survival, then you’re not going to get the behaviour that you want. If you tell me the car battery cost that much, or the electric vehicle cost that much, I might be looking at, oh geez, my goodness, how am I going to eat.” Robert contemplates.

The average electric vehicle costs around BDS $80,000 after concessions.

On the other hand, Delores looks at the tax concessionary period and wonders if extensions beyond 18 months are in the cards for taxi owners.

Couple Keturah Collymore and Anthony Warren also have questions and suggestions about the transition to electric vehicles.

The more optimistic Anthony believes the goal is doable but suggests that schools should provide an educational foundation on renewable energy as early as primary school.

Keturah shares a more sobering list of concerns about sourcing and disposing of ion batteries.

“But how are they recycled? Where did they go? Is it sustainable? Is it ethical to actually run this vehicle? Where did the batteries come from? Sometimes these batteries come from places where [they have] atrocious harvesting of the raw materials, and the recycling of them is even worse.”

Changing mindsets while sticking to agreed international protocols is tricky. It takes fair funding practices and a framework that allows people to maintain their basic needs. When people can support themselves, they are more amenable to looking at protocols.

For Fisherfolk, it is developing physical and social services that reduce livelihood threats, according to Dr Cox, as she works to develop workable ideas.

“There are some initiatives across the region, as it relates to building out adaptation measures, be it the use of climate-smart technologies, information, improve value chains, we are trying to build out that. [To have] affordable insurance as well as social security.”

The key is to develop protocols within protocols, constructing a system unique to Barbados while considering the cost of living.

Fashioning authentic policies opens doors to innovative ideas and careers in both areas of fishing and renewable energy.

In all cases, the Barbadian climate warrior, even though they did not start the battle, is willing to champion the cause as an example to the rest of the world. But the struggle must be waged on Barbados’ terms and benefit the country as well as the global climate, according to Hinds, the Chief Energy Officer Conservation Officer.

“Everything about Barbados’ size related to our economic development is minute. We are leaders and champions of the cause. It’s not just the minute contribution that we will make but it is the national impact that would happen to Barbados and other small island developing states, that is very important.”

Conversion rate

US $1 = BDS $2

More reading is available at:

Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley calls for reform to banking https://www.caribbeannationalweekly.com/uncategorized/barbados-pm-mia-mottley-calls-for-reform-of-world-bank/

“COURTESY GARAGE ELECTRIC VEHICLES” Clipped from: https://caribpix.net/barbados-courtesy-launches-newest-electric-vehicle-the-2022-nissan-leaf/

Barbados Physical Development Plan 2017

Barbados’ Second National Communication 2018

Planning & Development Department: Physical Development Plan website

This project supported by Open Society Foundations